A Vietnam veteran is an individual who performed active military, naval, or air service in the Republic of Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a mental and behavioral disorder that develops from experiencing a traumatic event, such as sexual assault, warfare, traffic collisions, child abuse, domestic violence, or other threats on a person's life. Symptoms may include disturbing thoughts, feelings, or dreams related to the events, mental or physical distress to trauma-related cues, attempts to avoid trauma-related cues, alterations in the way a person thinks and feels, and an increase in the fight-or-flight response. These symptoms last for more than a month after the event. Young children are less likely to show distress but instead may express their memories through play. A person with PTSD is at a higher risk of suicide and intentional self-harm.

A veteran is a person who has significant experience and expertise in a particular occupation or field. A military veteran is a person who is no longer in a military.

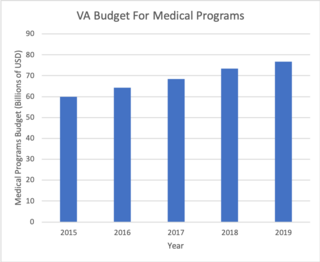

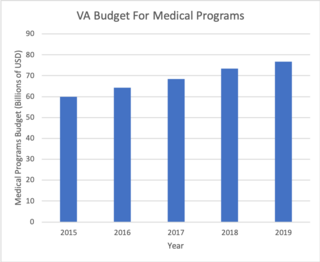

The Veterans Health Administration (VHA) is the component of the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) led by the Under Secretary of Veterans Affairs for Health that implements the healthcare program of the VA through a nationalized healthcare service in the United States, providing healthcare and healthcare-adjacent services to veterans through the administration and operation of 146 VA Medical Centers (VAMC) with integrated outpatient clinics, 772 Community Based Outpatient Clinics (CBOC), and 134 VA Community Living Centers Programs. It is the largest division in the Department, and second largest in the entire federal government, employing over 350,000 employees. All VA hospitals, clinics and medical centers are owned by and operated by the Department of Veterans Affairs, and all of the staff employed in VA hospitals are government employees. Because of this, veterans that qualify for VHA healthcare do not pay premiums or deductibles for their healthcare but may have to make copayments depending on the medical procedure. VHA is not a part of the US Department of Defense Military Health System.

Combat stress reaction (CSR) is acute behavioral disorganization as a direct result of the trauma of war. Also known as "combat fatigue", "battle fatigue", or "battle neurosis", it has some overlap with the diagnosis of acute stress reaction used in civilian psychiatry. It is historically linked to shell shock and can sometimes precurse post-traumatic stress disorder.

Complex post-traumatic stress disorder (CPTSD) is a stress-related mental disorder generally occurring in response to complex traumas, i.e. commonly prolonged or repetitive exposures to a series of traumatic events, within which individuals perceive little or no chance to escape.

Peer support occurs when people provide knowledge, experience, emotional, social or practical help to each other. It commonly refers to an initiative consisting of trained supporters, and can take a number of forms such as peer mentoring, reflective listening, or counseling. Peer support is also used to refer to initiatives where colleagues, members of self-help organizations and others meet, in person or online, as equals to give each other connection and support on a reciprocal basis.

Polytrauma and multiple trauma are medical terms describing the condition of a person who has been subjected to multiple traumatic injuries, such as a serious head injury in addition to a serious burn. The term is defined via an Injury Severity Score (ISS) equal to or greater than 16. It has become a commonly applied term by US military physicians in describing the seriously injured soldiers returning from Operation Iraqi Freedom in Iraq and Operation Enduring Freedom in Afghanistan. The term is generic, however, and has been in use for a long time for any case involving multiple trauma.

The Madigan Army Medical Center, located on Joint Base Lewis-McChord just outside Lakewood, Washington, is a key component of the Madigan Healthcare System and one of the largest military hospitals on the West Coast of the United States.

Raymond Monsour Scurfield is an American professor emeritus of social work, The University of Southern Mississippi, Gulf Coast. He retired in November, 2021 from private practice. He has continued as the external clinical consultant to the Biloxi VA Vet Center since 2011. He has been recognized for his expertise in war-related and natural disaster Psychological trauma and in meditation. He has published books and articles exploring the effects of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in both combat veterans and disaster survivors, including a trilogy of books about war’s impact. The trilogy’s third installment, War Trauma: Lessons Unlearned from Vietnam to Iraq, was published in October 2006. His three newest books are Scurfield, R.M. & Platoni, K.T. (Eds.). War Trauma & Its Wake. Expanding the Circle of Healing. New York & London: Routledge (2012); Scurfield, R.M. & Platoni, K.T. (Eds).Healing War Trauma. A Handbook of Creative Approaches. New York & London (2013); and Faith-Based and Secular Meditation: Everyday and Posttraumatic Applications. Washington, D.C.: NASW Press (2019)(see review on Amazon.com books).

Jonathan Shay is an American doctor and clinical psychiatrist. He holds a B.A from Harvard (1963), and an M.D. (1971) and a Ph.D. (1972) from the University of Pennsylvania. He is best known for his publications comparing the experiences of Vietnam veterans with the descriptions of war and homecoming in Homer's Iliad and Odyssey.

Combat Stress is a registered charity in the United Kingdom offering therapeutic and clinical community and residential treatment to former members of the British Armed Forces who are suffering from a range of mental health conditions; including post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Combat Stress makes available treatment for all Veterans who are suffering with mental illness free of charge.

The United States has compensated military veterans for service-related injuries since the Revolutionary War, with the current indemnity model established near the end of World War I. The Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) began to provide disability benefits for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in the 1980s after the diagnosis became part of official psychiatric nosology.

Jon Elhai is a professor of clinical psychology at the University of Toledo. Elhai is known for being an expert in the assessment and diagnosis of Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), forensic psychological assessment of PTSD, and detection of fabricated/malingered PTSD; as well as in internet addictions.

A moral injury is an injury to an individual's moral conscience and values resulting from an act of perceived moral transgression on the part of themselves or others. It produces profound feelings of guilt or shame, moral disorientation, and societal alienation. In some cases it may cause a sense of betrayal and anger toward colleagues, commanders, the organization, politics, or society at large.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) results after experiencing or witnessing a terrifying event which later leads to mental health problems. This disorder has always existed but has only been recognized as a psychological disorder within the past forty years. Before receiving its official diagnosis in 1980, when it was published in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-lll), Post-traumatic stress disorder was more commonly known as soldier's heart, irritable heart, or shell shock. Shell shock and war neuroses were coined during World War I when symptoms began to be more commonly recognized among many of the soldiers that had experienced similar traumas. By World War II, these symptoms were identified as combat stress reaction or battle fatigue. In the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-I), post-traumatic stress disorder was called gross stress reaction which was explained as prolonged stress due to a traumatic event. Upon further study of this disorder in World War II veterans, psychologists realized that their symptoms were long-lasting and went beyond an anxiety disorder. Thus, through the effects of World War II, post-traumatic stress disorder was eventually recognized as an official disorder in 1980.

Home Before Morning: The Story of an Army Nurse in Vietnam is a memoir written by American writer Lynda Van Devanter in 1983. The memoir, originally published by Beaufort Books, explores Van Devanter's experience as a nurse during the Vietnam War. It was adapted into a popular TV show, China Beach, which ran from 1988 to 1991.

Psychological trauma in adultswho are older, is the overall prevalence and occurrence of trauma symptoms within the older adult population.. This should not to be confused with geriatric trauma. Although there is a 90% likelihood of an older adult experiencing a traumatic event, there is a lack of research on trauma in older adult populations. This makes research trends on the complex interaction between traumatic symptom presentation and considerations specifically related to the older adult population difficult to pinpoint. This article reviews the existing literature and briefly introduces various ways, apart from the occurrence of elder abuse, that psychological trauma impacts the older adult population.

The George E. Wahlen Veterans Affairs Medical Center (VAMC) is located in Salt Lake City, Utah. The George E. Wahlen VA Hospital is a 121-bed short-term acute care hospital and is designated as a medical training and research facility. For the scale of operations in 2019, the George E. Wahlen VA had over 2,500 employees, treated over 66,000 veterans, and accommodated nearly 390,000 outpatient visits. Of the veterans treated here in 2019, 24,514 served in the Gulf War, 25,714 served in the Vietnam War, 1,290 in World War II, 3,377 served in the Korean War, and 7,286 were women. During 2019, the George E. Wahlen VA federal budget allocation was approximately $668 million. The George E. Wahlen Medical Center is one of five heart transplant centers in the United States. The facility is encompassed within the Veterans Integrated Service Network 19 within the Rocky Mountain Region.

Jessica M. Gill is an American nurse scientist working as a Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Trauma Recovery Biomarkers in the department of neurology at the Johns Hopkins School of Nursing and School of Medicine since 2021. She was the acting deputy director of the National Institute of Nursing Research from 2019 to 2020 and deputy director of the Center for Neuroscience and Regenerative Medicine at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences until 2021.