Related Research Articles

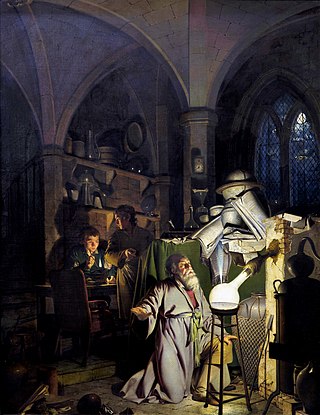

Alchemy is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, and Europe. In its Western form, alchemy is first attested in a number of pseudepigraphical texts written in Greco-Roman Egypt during the first few centuries AD.

In Greek mythology, Chryseis is a Trojan woman, the daughter of Chryses. Chryseis, her apparent name in the Iliad, means simply "Chryses' daughter"; later writers give her real name as Astynome (Ἀστυνόμη). The 12th century poet Tzetzes describes her to be "very young and thin, with milky skin; had blond hair and small breasts; nineteen years old and still a virgin".

The philosopher's stone, or more properly philosophers' stone, is a mythic alchemical substance capable of turning base metals such as mercury into gold or silver. It is also called the elixir of life, useful for rejuvenation and for achieving immortality; for many centuries, it was the most sought-after goal in alchemy. The philosopher's stone was the central symbol of the mystical terminology of alchemy, symbolizing perfection at its finest, enlightenment, and heavenly bliss. Efforts to discover the philosopher's stone were known as the Magnum Opus.

Hermeticism or Hermetism is a philosophical and religious system based on the purported teachings of Hermes Trismegistus. These teachings are contained in the various writings attributed to Hermes, which were produced over a period spanning many centuries and may be very different in content and scope.

The ouroboros or uroboros is an ancient symbol depicting a serpent or dragon eating its own tail. The ouroboros entered Western tradition via ancient Egyptian iconography and the Greek magical tradition. It was adopted as a symbol in Gnosticism and Hermeticism and most notably in alchemy.

Andreas Libavius or Andrew Libavius was born in Halle, Germany c. 1550 and died in July 1616. Libavius was a renaissance man who spent time as a professor at the University of Jena teaching history and poetry. After which he became a physician at the Gymnasium in Rothenburg and later founded the Gymnasium at Coburg. Libavius was most known for practicing alchemy and writing a book called Alchemia, one of the first chemistry textbooks ever written.

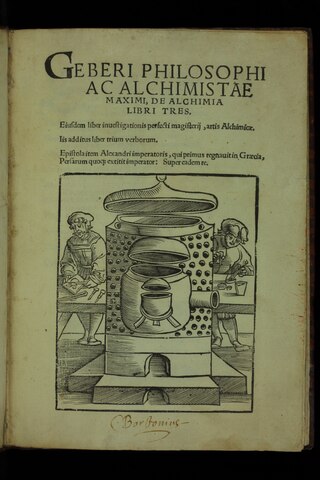

Pseudo-Geber is the presumed author or group of authors responsible for a corpus of pseudepigraphic alchemical writings dating to the late 13th and early 14th centuries. These writings were falsely attributed to Jabir ibn Hayyan, an early alchemist of the Islamic Golden Age.

The University of Strasbourg is a public research university located in Strasbourg, France, with over 52,000 students and 3,300 researchers. Founded in the 16th century by Jean Sturm, it was an intellectual hotbed during the Age of Enlightenment.

Fortunio Liceti, was an Italian physician and philosopher.

Conrad Dasypodius was a professor of mathematics in Strasbourg, Alsace. He was born in Frauenfeld, Thurgau, Switzerland. His first name was also rendered as Konrad or Conradus or Cunradus, and his last name has been alternatively stated as Rauchfuss, Rauchfuß, and Hasenfratz. He was the son of Petrus Dasypodius, a humanist and lexicographer.

Giovanni Aurelio Augurello (1441–1524) was an Italian humanist scholar, poet and alchemist. Born at Rimini, he studied both laws in Rome, Florence and Padova where he also consorted with the leading scholars of his time. At Florence he befriended Marsilio Ficino (1433-1499) and Angelo Poliziano (1454-1494) and later while teaching classics in Treviso joined Aldo Mantius' humanist circle in Venice. Apart from his academic and literary work he practically experimented in metallurgy and provided colour pigments for his friend the Hermetic painter Giulio Campagnola He is best known for his 1515 allegorical poem on the making of gold, Chrysopoeia, which was dedicated to Pope Leo X; leading to the famous but forged anecdote that the Pope had rewarded Augurello with a beautiful but empty purse as an alchemist like him should on his own to be capable of replenishing it — he was actually bestowed with a sinecure at the cathedral of Treviso.

Monas Hieroglyphica is a book by John Dee, the Elizabethan magus and court astrologer of Elizabeth I of England, published in Antwerp in 1564. It is an exposition of the meaning of an esoteric symbol that he invented.

Theatrum Chemicum is a compendium of early alchemical writings published in six volumes over the course of six decades. The first three volumes were published in 1602, while the final sixth volume was published in its entirety in 1661. Theatrum Chemicum remains the most comprehensive collective work on the subject of alchemy ever published in the Western world.

Arnold Vinnius was one of the leading jurists of the 17th century in the Netherlands.

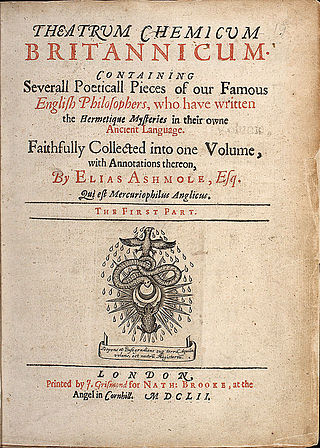

Theatrum Chemicum Britannicum first published in 1652, is an extensively annotated compilation of English alchemical literature selected by Elias Ashmole. The book preserved and made available many works that had previously existed only in privately held manuscripts. It features the alchemical verse of people such as Thomas Norton, George Ripley, Geoffrey Chaucer, John Gower, John Lydgate, John Dastin, Abraham Andrews and William Backhouse.

Bernard Gilles Penot was a French Renaissance alchemist and a friend of Nicolas Barnaud.

John of Wales, also called John Waleys and Johannes Guallensis, was a Franciscan theologian who wrote several well-received Latin works, primarily preaching aids.

Balthasar Moretus or Balthasar I Moretus was a Flemish printer and head of the Officina Plantiniana, the printing company established by his grandfather Christophe Plantin in Antwerp in 1555. He was the son of Martina Plantin and Jan Moretus.

Guglielmo Gratarolo or Grataroli or Guilelmus Gratarolus was an Italian doctor and alchemist.

Thomas Reiser is a German philologist and translator. His contributions range from Baroque alchemy to comedies and art technological treatises of classical antiquity as well as of the Italian Renaissance. In 2014 he saw to the first German translation of Francesco Colonna’s Hypnerotomachia Poliphili.

References

- Erich Egg, Der Straßburger Goldschmied Josias Barbette, in: Waffen- und Kostümkunde 2 (1966), pp. 126–130. ISSN 0042-9945

- Yasmin Haskell: Round and Round we go: The Alchemical Opus circulatorium of Giovanni Aurelio Augurelli , in: Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance 59 (1997), pp. 585–606. ISSN 0006-1999

- Didier Kahn, Alchemical Poetry in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: A Preliminary Survey and Synthesis, Part I in: Ambix 57/3 (2010), pp. 249–274; Part II in: Ambix 58/1 (2011), pp. 62–77. ISSN 0002-6980

- Wilhelm Kühlmann, Alchemie und späthumanistische Formkultur, Der Straßburger Dichter Johann Nicolaus Furichius (1602–1633), ein Freund Moscheroschs , in: Daphnis 13 (1984), pp. 101–135. ISSN 0300-693X

- Zweder von Martels, The Allegorical Meaning of the Chrysopoeia by Ioannes Aurelius Augurellus , in: Acta Conventus Neo-Latini Hafniensis, Proceedings of the Eight International Congress of Neo-Latin Studies, Copenhagen 12 August to 17 August 1991, Rhoda Schnur et al. (edd.), Birmingham-New York 1994, pp. 979–988. ISBN 0-86698-173-X

- Zweder von Martels, Augurello's Chrysopoeia (1515): a turning point in the literary tradition of alchemical texts, in: Early Science and Medicine 5/2 (2000), pp. 178–195. ISSN 1383-7427

- Sylvain Matton, L'hérmeneutique alchimique da la fable antique, in: Antoine-Joseph Pernety, Les fables égyptiennes et grecques, 2 vols, Paris 1786 (reprint ibid. 1991), vol. 1, pp. 1–24. ISBN 2-903965-19-6

- Giuseppe Pavanello, Un maestro del quattrocento, Giovanni Aurelio Augurello , Venice 1905.

- Thomas Reiser, Furichius, Johannes Nicolaus, in Killy Literaturlexikon , 2nd revised edition, Wilhelm Kühlmann et al. (edd.), 13 vols, Berlin 2008sqq., vol. 4 (2009), wpp. 87–88. ISBN 978-3-11-021389-8

- Thomas Reiser, Mythologie und Alchemie in der Lehrepik des frühen 17. Jahrhunderts, Die Chryseidos libri IIII des Straßburger Dichterarztes Johannes Nicolaus Furichius (1602–1633), Tübingen: De Gruyter 2011. ISBN 978-3-11-023316-2 – review by Fredericka A. Schmadel in: Journal of Folklore Research (online).

- Lucia Rosetti (ed.), Matricula Nationis Germanicae Artistarum Gymnasio Patavino (1553–1721), Padua 1986. ISBN 978-88-8455-326-3

- Heinrich Schneider, Joachim Morsius und sein Kreis, Zur Geschichte des 17. Jahrhunderts, Lübeck 1929.

- François Secret, Alchimie et Mythologie, in: Dictionnaire des mythologies et réligions des sociétés traditionelles et du monde antique, Yves Bonnefoi (ed.), 2 vols, Paris 1981, vol. 1, pp. 7–9. ISBN 2-08-010945-6