Related Research Articles

Consubstantiation is a Christian theological doctrine that describes the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist. It holds that during the sacrament, the substance of the body and blood of Christ are present alongside the substance of the bread and wine, which remain present. It was part of the doctrines of Lollardy, and considered a heresy by the Roman Catholic Church. It was later championed by Edward Pusey of the Oxford Movement, and is therefore held by many high church Anglicans.

Transubstantiation is, according to the teaching of the Catholic Church, "the change of the whole substance of bread into the substance of the Body of Christ and of the whole substance of wine into the substance of his Blood". This change is brought about in the eucharistic prayer through the efficacy of the word of Christ and by the action of the Holy Spirit. However, the outward characteristics of bread and wine, that is the 'eucharistic species', remain unaltered. In this teaching, the notions of "substance" and "transubstantiation" are not linked with any particular theory of metaphysics.

Martin Bucer was a German Protestant reformer based in Strasbourg who influenced Lutheran, Calvinist, and Anglican doctrines and practices. Bucer was originally a member of the Dominican Order, but after meeting and being influenced by Martin Luther in 1518 he arranged for his monastic vows to be annulled. He then began to work for the Reformation, with the support of Franz von Sickingen.

Crypto-Calvinism is a pejorative term describing a segment of German members of the Lutheran Church accused of secretly subscribing to Calvinist doctrine of the Eucharist in the decades immediately after the death of Martin Luther in 1546.

The real presence of Christ in the Eucharist is the Christian doctrine that Jesus Christ is present in the Eucharist, not merely symbolically or metaphorically, but in a true, real and substantial way.

In Christian theology, the term Body of Christ has two main but separate meanings: it may refer to Jesus' words over the bread at the celebration of the Jewish feast of Passover that "This is my body" in Luke 22:19–20, or it may refer to all individuals who are "in Christ" 1 Corinthians 12:12–14.

Formula of Concord (1577) is an authoritative Lutheran statement of faith that, in its two parts, makes up the final section of the Lutheran Corpus Doctrinae or Body of Doctrine, known as the Book of Concord.

The Ubiquitarians, also called Ubiquists, were a Protestant sect that held that the body of Christ was everywhere, including the Eucharist. The sect was started at the Lutheran synod of Stuttgart, 19 December 1559, by Johannes Brenz (1499–1570), a Swabian. Its profession, made under the name of Duke Christopher of Württemberg and entitled the "Württemberg Confession," was sent to the Council of Trent in 1552, but had not been formally accepted as the Ubiquitarian creed until the synod at Stuttgart.

Eucharistic theology is a branch of Christian theology which treats doctrines concerning the Holy Eucharist, also commonly known as the Lord's Supper. It exists exclusively in Christianity and related religions, as others generally do not contain a Eucharistic ceremony.

Sacramental union is the Lutheran theological doctrine of the Real Presence of the body and blood of Christ in the Christian Eucharist.

Wittenberg Concord, is a religious concordat signed by Reformed and Lutheran theologians and churchmen on 29 May 1536 as an attempted resolution of their differences with respect to the Real Presence of Christ's body and blood in the Eucharist. It is considered a foundational document for Lutheranism but was later rejected by the Reformed.

Lutheranism as a religious movement originated in the early 16th century Holy Roman Empire as an attempt to reform the Roman Catholic Church. The movement originated with the call for a public debate regarding several issues within the Catholic Church by Martin Luther, then a professor of Bible at the young University of Wittenberg. Lutheranism soon became a wider religious and political movement within the Holy Roman Empire owing to support from key electors and the widespread adoption of the printing press. This movement soon spread throughout northern Europe and became the driving force behind the wider Protestant Reformation. Today, Lutheranism has spread from Europe to all six populated continents.

Manducatio impiorum refers to those who eat the Lord’s Supper but do not believe all Christian doctrine including the rejection of the real presence in the Lord’s Supper. Martin Luther and the Gnesio Lutherans held to this view, which is codified in the Epitome of the Formula of Concord VII found in the Book of Concord. Philipp Melanchthon and his followers, the Philippists, with the Reformed denied this teaching including Huldrych Zwingli and John Calvin Calvin believed that Christ's body is given to all communicants, but only received by those who have faith. Lutherans refer to this as the receptionist error. It relates to doctrine of the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, and, in particular, to the interpretation of 1 Corinthians 11:27–29:

The Philippists formed a party in early Lutheranism. Their opponents were called Gnesio-Lutherans.

Joachim Westphal was a German "Gnesio-Lutheran" theologian and Protestant reformer.

Gnesio-Lutherans is a modern name for a theological party in the Lutheran churches, in opposition to the Philippists after the death of Martin Luther and before the Formula of Concord. In their own day they were called Flacians by their opponents and simply Lutherans by themselves. Later Flacian became to mean an adherent of Matthias Flacius' view of original sin, rejected by the Formula of Concord. In a broader meaning, the term Gnesio-Lutheran is associated mostly with the defence of the doctrine of Real Presence.

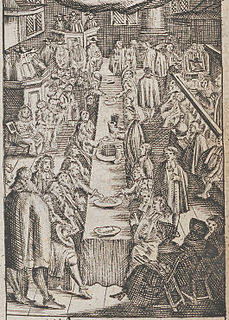

The Eucharist in the Lutheran Church refers to the liturgical commemoration of the Last Supper. Lutherans believe in the real presence of Christ in the Eucharist, affirming the doctrine of sacramental union, "in which the body and blood of Christ are truly and substantially present, offered, and received with the bread and wine."

The Lutheran sacraments are "sacred acts of divine institution". Lutherans believe that, whenever they are properly administered by the use of the physical component commanded by God along with the divine words of institution, God is, in a way specific to each sacrament, present with the Word and physical component. They teach that God earnestly offers to all who receive the sacrament forgiveness of sins and eternal salvation. They teach that God also works in the recipients to get them to accept these blessings and to increase the assurance of their possession.

The Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ—Against the Fanatics is a book by Martin Luther, published in late September or early October 1526 to aid Germans confused by the spread of new ideas from the Sacramentarians. At issue was whether Christ's true body and blood were present in the Lord's Supper, a doctrine that came to be known as the sacramental union.

In Reformed theology, the Lord's Supper or Eucharist is a sacrament that spiritually nourishes Christians and strengthens their union with Christ. The outward or physical action of the sacrament is eating bread and drinking wine. Reformed confessions, which are official statements of the beliefs of Reformed churches, teach that Christ's body and blood are really present in the sacrament, but that this presence is communicated in a spiritual manner rather than by his body being physically eaten. The Reformed doctrine of real presence is called "pneumatic presence".

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Guy R. Purdue (31 October 1995). "... III. The Saliger Controversy" (PDF). Contemporary Questions Concerning The Moment Of The Real Presence In The Lord’s Supper. pp. 10–23. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- 1 2 3 Ludwig Fromm (1875). "Beatus: Johann B. (Saliger, Seliger), geb. zu Lübeck, lutherischer Prediger zu Wörden ..." Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie . Historische Kommission bei der Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften. p. 191. Retrieved 19 June 2017.

- ↑ Johann Bernhard Krey (1816). Andenken an die Rostockschen Gelehrten aus den drei letzten Jahrhunderten. Adler. p. 6.

- ↑ Archiv für Staats- und Kirchengeschichte der Herzogthümer Schleswig, Holstein, Lauenburg und der angrenzenden Länder und Städte. Hammerich. 1837. pp. 208–209.