Related Research Articles

The Swing Riots were a widespread uprising in 1830 by agricultural workers in southern and eastern England in protest of agricultural mechanisation and harsh working conditions. The riots began with the destruction of threshing machines in the Elham Valley area of East Kent in the summer of 1830 and by early December had spread through the whole of southern England and East Anglia. It was to be the largest movement of social unrest in 19th-century England.

Fleet is a village, civil parish and electoral ward in the South Holland district of Lincolnshire, England. It lies on Delph Bank, 3 miles (4.8 km) south-east from Holbeach. The population of the civil parish, including Fleet Hargate, at the 2011 census was 2136.

Sir John Arthur Ransome Marriott was a British educationist, historian, and Conservative member of parliament (MP).

Aylesby is a village and civil parish in North East Lincolnshire, England. It is situated near the A18 road, approximately 4 miles (6 km) west from Cleethorpes and north of Laceby. The population at the 2001 census was 135, increasing to 155 at the 2011 Census.

Brigsley is a village and civil parish in North East Lincolnshire, England, and on the B1203 road, 1 mile (1.6 km) south from Waltham.

Bucknall is a village and civil parish in the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. The village is situated approximately 5 miles (8 km) west from Horncastle and 5 miles (8 km) north from Woodhall Spa.

The Master of the Jewel Office was a position in the Royal Households of England, the Kingdom of Great Britain and the United Kingdom. The office holder was responsible for running the Jewel House, which houses the Crown Jewels. This role has, at various points in history, been called Master or Treasurer of the Jewel House, Master or Keeper of the Crown Jewels, Master or Keeper of the Regalia, and Keeper of the Jewel House. In 1967, the role was combined with Resident Governor of the Tower of London.

Grayingham is a village and civil parish in the West Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. The population of the civil parish at the 2011 census was 123 It is situated 1 mile (1.6 km) south from Kirton in Lindsey, 8 miles (13 km) north-east from Gainsborough and 8 miles south from Scunthorpe.

Caenby is a hamlet and civil parish in the West Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. It is situated 10 miles (16 km) north of the city and county town of Lincoln. The population is included in the civil parish of Glentham.

Haugham is a village and civil parish in the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. It is situated 3 miles (5 km) south from Louth. The prime meridian passes directly through Haugham.

Friskney is a village and civil parish within the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England.

Mumby is a village in the East Lindsey district of Lincolnshire, England. It is located 4 miles (6 km) south-east from the town of Alford. In 2001 the population was recorded as 352, increasing to 447 at the 2011 Census.

Croxton is a civil parish in North Lincolnshire, England. It is situated just south from the A180, 1 mile (1.6 km) north-west from Kirmington and 7 miles (11 km) west from Immingham.

Sir William Wray, 1st Baronet, of Glentworth, Lincolnshire was an English Member of Parliament.

Rev. Peter Hampson Ditchfield, FSA was a Church of England priest, historian and prolific author. He is notable for having co-edited three Berkshire volumes of the Victoria County History which were published between 1907 and 1924.

English county histories, in other words historical and topographical works concerned with individual ancient counties of England, were produced by antiquarians from the late 16th century onwards. The content was variable: most focused on recording the ownership of estates and the descent of lordships of manors, thus the genealogies of county families, heraldry and other antiquarian material. In the introduction to one typical early work of this style, The Antiquities of Warwickshire published in 1656, the author William Dugdale writes:

I offer unto you my noble countriemen, as the most proper persons to whom it can be presented wherein you will see very much of your worthy ancestors, to whose memory I have erected it as a monumentall pillar and to shew in what honour they lived in those flourishing ages past. In this kind, or not much different, have divers persons in forrein parts very learnedly written; some whereof I have noted in my preface: and I could wish that there were more that would adventure in the like manner for the rest of the counties of this nation, considering how acceptable those are, which others have already performed

Culverthorpe is a hamlet in the civil parish of Culverthorpe and Kelby, in the North Kesteven district of Lincolnshire, England. It lies 5 miles (8 km) south-west from Sleaford, 9 miles (14 km) north-east from Grantham and 3 miles (5 km) south-east from Ancaster.

John Henry Overton, VD, DD (hon) (1835–1903) was an English cleric, known as a church historian.

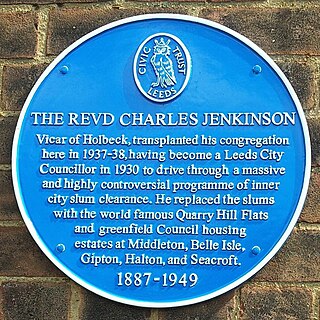

Charles Jenkinson was a Church of England clergyman, housing reformer, and Leeds councillor.

Rotha Mary Clay was a British self-taught historian and social worker.

References

- 1 2 3 Nurse, Bernard. "Cox, John Charles". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/41055.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Elizabeth T. Hurren (18 June 2015). Protesting about Pauperism: Poverty, Politics and Poor Relief in Late-Victorian England, 1870-1900. Boydell & Brewer Ltd. p. 227. ISBN 978-0-86193-329-7.

- ↑ Abbot 2000.

- ↑ Nick Poyntz, J. Charles Cox, Mercurius Politicus. Retrieved on 6 May 2017.

- ↑ Matthew, H. C. G.; Harrison, B., eds. (23 September 2004). "The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography" . Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. ref:odnb/61734. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/61734 . Retrieved 27 February 2023.(Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ "A Radical Historian's Pursuit of Rural History: The Political Career and Contribution of Reverend Dr. John Charles Cox, c. 1844 to 1919", Elizabeth T. Hurren, Rural History, Volume 19, Issue 1, April 2008, pp. 81-103. Retrieved on 6 May 2016.

- ↑ Cox, John Charles; Cox, Henry F. (1874). The Rise of the Farm Labourer: a Series of Articles ... Illustrative of Certain Political Aspects of the Agricultural Labour Movement.

- ↑ John Charles Cox (1879). How to Write the History of a Parish. Bemrose & Sons.

- ↑ Rev. J. Charles Cox, How to Write the History of a Parish: An Outline Guide to Topographical Records, Manuscripts, and Books, London: George Allen & Sons, 1909, 5th edition, revised. Retrieved on 6 May 2017.

- ↑ Joseph Strutt (1801). The Sports and Pastimes of the People of England: From the Earliest Period, Including the Rural and Domestic Recreations, May Games, Mummeries, Pageants, Processions and Pompous Spectacles. Methuen & Company.

- ↑ J Charles Cox (10 September 2010). The Royal Forests of England (1905). Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-164-10460-5.

- ↑ John Charles Cox; Alfred Harvey (1908). English Church Furniture. Methuen.

- ↑ J. Charles Cox (1910). The Parish Registers of England. Methuen.

- ↑ John Charles Cox (1911). The Sanctuaries and Sanctuary Seekers of Mediaeval England. G. Allen & sons.

- ↑ J Charles Cox (1914). The English Parish Church. B. T. Batsford.

- ↑ J. Charles Cox (1916), Lincolnshire, Methuen & Co. Ltd. Retrieved 10 January 2019