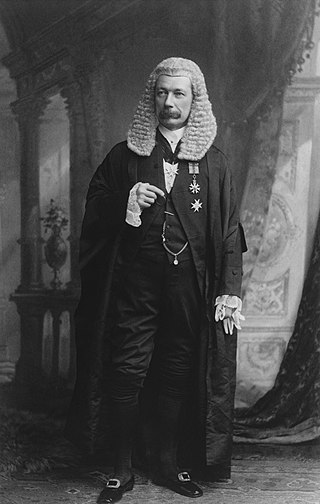

John Walter Hulme (1805-1861) was a British lawyer and Judge. He was the first Chief Justice of Hong Kong, taking office in 1844.

John Walter Hulme (1805-1861) was a British lawyer and Judge. He was the first Chief Justice of Hong Kong, taking office in 1844.

Hulme was born in 1805 in Fenton, Staffordshire, England. He was the son of a "highly respectable solicitor." [1]

He was called to the Bar of the Middle Temple in 1829. He served his pupillage with the noted barrister and author Joseph Chitty. He was a co-author with Chitty of A Practical Treatise on Bills of Exchange and A Collection of Statutes of Practical Utility. He also married Chitty's daughter, Eliza. [2] : 48, 657

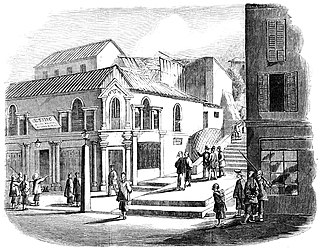

Hong Kong was ceded to the United Kingdom in 1842 under the Treaty of Nanking. Initially, a military government was formed. In 1844, civilian government was put in place under Governor John Francis Davis.

Hulme was appointed the first Chief Justice of Hong Kong. The Colonial Office had great difficulty in finding a judge willing to go to the newly established colony. Hulme was offered the very high salary of £3,000 per annum to go to Hong Kong; in return, he agreed to give up his right to a pension.

He arrived in Hong Kong on 7 May 1844 on board the H.M.S. Spitfire together with Davis and other officials. He was also appointed as a member of the Hong Kong Legislative Council. The Supreme Court was formally opened on 1 October 1844 with Hulme on the bench. [3] : 47–49, 64–65

As Chief Justice, Hulme fearlessly protected the independence of the judiciary. He had a number of run-ins with Governor Davis that culminated in charges of drunkenness being brought against him. The charge against him read that he had been "in a state of intoxication as to attract public attention when attending a public entertainment given by Rear Admiral Thomas Cockrane on November 22, 1845". In 1847, he was brought before the Executive Council of Hong Kong, who found him guilty and suspended him from his position. On 30 December 1847, Hulme returned to England; the Colonial Secretary refused to uphold the verdict and he soon returned to Hong Kong. [3] : 157–8

In November 1846, Hulme refused to uphold a guilty verdict against a Mr Compton that had been handed down by the British consular court in Canton. Compton, an English merchant, was fined HK$200 for causing a riot by kicking over a Chinese stall and beating its owner with his stick, and appealed to the Supreme Court of Hong Kong. Hulme was highly critical of the way in which the case had been handled. Sir John Davis, the Governor of Hong Kong wrote to Lord Palmerston, the Prime Minister, stating: "Some fresh ordinance will inevitably be required to prevent such mischievous interference in international cases." [4]

In February 1857, Hulme presided at the trial of ten Chinese men who had been charged in connection to a mass poisoning of Europeans in Hong Kong known as the Esing Bakery incident. The Attorney General, Thomas Chisholm Anstey, argued that the principal suspect, Cheong Ah-lum, should be hanged regardless of his innocence because it was "better to hang the wrong man than confess that British sagacity and activity have failed to discover the real criminals". Hulme replied that "hanging the wrong man will not further the ends of justice", and later accepted the jury's acquittal of Cheong. [5]

Hulme became very unwell to the end of his term of office and often would only commence court sitting at noon or 1pm. He was put under pressure to retire, but insisted that he be given a pension. He left Hong Kong on leave in early 1859 and in England was offered a handsome pension of £1,500 per annum which he accepted. [6]

Hulme died soon after his retirement, on 1 March 1861 in Brighton. [7]

The governor of Hong Kong was the representative of the British Crown in Hong Kong from 1843 to 1997. In this capacity, the governor was president of the Executive Council and commander-in-chief of the British Forces Overseas Hong Kong. The governor's roles were defined in the Hong Kong Letters Patent and Royal Instructions. Upon the end of British rule and the handover of Hong Kong to China in 1997, most of the civil functions of this office went to the chief executive of Hong Kong, and military functions went to the commander of the People's Liberation Army Hong Kong Garrison.

Sir Ti-liang Yang, was a Hong Kong judge. He was the Chief Justice of Hong Kong from 1988 to 1996, the only ethnic Chinese person to hold this office during British colonial rule.

Karl Friedrich August Gützlaff, anglicised as Charles Gutzlaff, was a German Lutheran missionary to the Far East, notable as one of the first Protestant missionaries in Bangkok, Thailand (1828) and in Korea (1832). He was also the first Lutheran missionary to China. He was a magistrate in Ningbo and Zhoushan and the second Chinese Secretary of the British administration in Hong Kong.

Sir John Francis Davis, 1st Baronet was a British diplomat and sinologist who served as second Governor of Hong Kong from 1844 to 1848. Davis was the first President of Royal Asiatic Society Hong Kong.

The Supreme Court of Hong Kong was the highest court in Hong Kong prior to the transfer of sovereignty of Hong Kong from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China in 1997 and heard cases of first instance and appeals from the District and Magisrates Courts as well as certain tribunals. The Supreme Court was from 1976 made up of the High Court of Justice and the Court of Appeal.

Major-General Sir George Charles d'Aguilar, ; January 1784 – 21 May 1855), was a British Army officer who served as Lieutenant Governor of Hong Kong (1843–1848).

Admiral Sir Charles Elliot was a British Royal Navy officer, diplomat, and colonial administrator. He became the first Administrator of Hong Kong in 1841 while serving as both Plenipotentiary and Chief Superintendent of British Trade in China. He was a key founder in the establishment of Hong Kong as a British colony.

John Robert Morrison was a British interpreter and colonial official in China. Born in Macau, his father was Robert Morrison, the first Protestant missionary in China. After his father's death in 1834, Morrison replaced him as Chinese Secretary and Interpreter to the Superintendents of British Trade in China. In 1843, he was appointed as Acting Colonial Secretary of Hong Kong and a member of the Executive and Legislative Councils, but died eight days later in Hong Kong from fever.

William Caine was the first head of the Hong Kong Police Force, Colonial Secretary of Hong Kong from 1846 to 1854. He attained the rank of Lieutenant Colonel prior to his secretary appointment. Caine was also the acting Governor of Hong Kong between May and September 1859.

Sir James Russell was an Irish colonial administrator in Hong Kong and served as Chief Justice of Hong Kong from 1888 to 1892.

Sir Francis Fleming was a British administrator who held appointments in eleven colonies.

Sir Frederick William Adolphus Wright-Bruce, GCB was a British diplomat.

William Henry Adams was a British politician, lawyer and colonial judge. His final appointment was as Chief Justice of Hong Kong.

Sir John Jackson Smale was a British lawyer and judge. He served as Attorney General and the longest-serving Chief Justice of Hong Kong.

Sir John Worrell Carrington, was a British jurist, elected representative, and colonial administrator between 1872 and 1902. He served the Caribbean colonies of Barbados, St. Lucia, Tobago, Grenada, and British Guiana until his final appointment as Chief Justice of Hong Kong.

Paul Ivy Sterling was a British lawyer and Judge. He served as the first Attorney General of Hong Kong and as a Puisne Judge in Ceylon .

James William Norton-Kyshe (1855–1920) was a British barrister and legal author. The Registrar of the Supreme Court of Hong Kong from 1895 to 1904, he published a number of law books including the compendious and oft-cited History of the Laws and Courts of Hong Kong (1898).

David Jardine (1818–1856) was a Scottish merchant in China and Hong Kong and the member of the Legislative Council of Hong Kong.

William Tarrant was a civil servant and newspaper editor in British Hong Kong. He served as Inspector of Land and Roads and subsequently Registrar of Deeds in the Hong Kong colonial administration from 1842 to 1847, but was removed from office and barred from public service owing to allegations he had raised against Colonial Secretary William Caine, which an internal government inquiry held to be fabricated. Tarrant then began a new career in journalism, purchasing the Friend of China newspaper in 1850. He became prominently involved in a scandal involving multiple senior government officers, the Caldwell affair, in 1857, and was ultimately found guilty of libel and imprisoned in 1859. He left the colony after his release in 1860, and made two attempts over the course of the 1860s to restart the Friend of China in Guangzhou and Shanghai, each proving abortive. Finally, he sold the paper in 1869 and retired to England, where he died in 1872.

The Esing Bakery incident, also known as the Ah Lum affair, was a food contamination scandal in the early history of British Hong Kong. On 15 January 1857, during the Second Opium War, several hundred European residents were poisoned non-lethally by arsenic, found in bread produced by a Chinese-owned store, the Esing Bakery. The proprietor of the bakery, Cheong Ah-lum, was accused of plotting the poisoning but was acquitted in a trial by jury. Nonetheless, Cheong was successfully sued for damages and was banished from the colony. The true responsibility for the incident and its intention—whether it was an individual act of terrorism, commercial sabotage, a war crime orchestrated by the Qing government, or purely accidental—both remain a matter of debate.