Related Research Articles

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to critical theory:

The labor theory of value (LTV) is a theory of value that argues that the economic value of a good or service is determined by the total amount of "socially necessary labor" required to produce it.

In economics, the means of production is a term which describes land, labor, and capital that can be used to produce products ; however, the term can also refer to anything that is used to produce products. It can also be used as an abbreviation of the "means of production and distribution" which additionally includes the logistical distribution and delivery of products, generally through distributors; or as an abbreviation of the "means of production, distribution, and exchange" which further includes the exchange of distributed products, generally to consumers.

Karl Marx's theory of alienation describes the experience of human life as meaningless or the human self as worthless in modern capitalist society. It is Marx’s earliest recognizable attempt at a systematic explanatory theory of capitalism.

In Marxist philosophy, the term commodity fetishism describes the economic relationships of production and exchange as being social relationships that exist among things and not as relationships that exist among people. As a form of reification, commodity fetishism presents economic value as inherent to the commodities, and not as arising from the workforce, from the human relations that produced the commodity, the goods and the services.

The term culture industry was coined by the critical theorists Theodor Adorno (1903–1969) and Max Horkheimer (1895–1973), and was presented as critical vocabulary in the chapter "The Culture Industry: Enlightenment as Mass Deception", of the book Dialectic of Enlightenment (1947), wherein they proposed that popular culture is akin to a factory producing standardized cultural goods—films, radio programmes, magazines, etc.—that are used to manipulate mass society into passivity. Consumption of the easy pleasures of popular culture, made available by the mass communications media, renders people docile and content, no matter how difficult their economic circumstances. The inherent danger of the culture industry is the cultivation of false psychological needs that can only be met and satisfied by the products of capitalism; thus Adorno and Horkheimer perceived mass-produced culture as especially dangerous compared to the more technically and intellectually difficult high arts. In contrast, true psychological needs are freedom, creativity, and genuine happiness, which refer to an earlier demarcation of human needs, established by Herbert Marcuse.

Abstract labour and concrete labour refer to a distinction made by Karl Marx in his critique of political economy. It refers to the difference between human labour in general as economically valuable worktime versus human labour as a particular activity that has a specific useful effect within the (capitalist) mode of production.

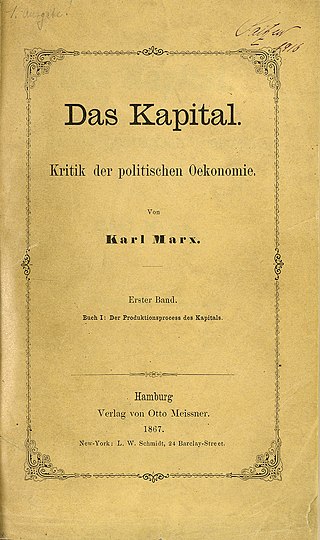

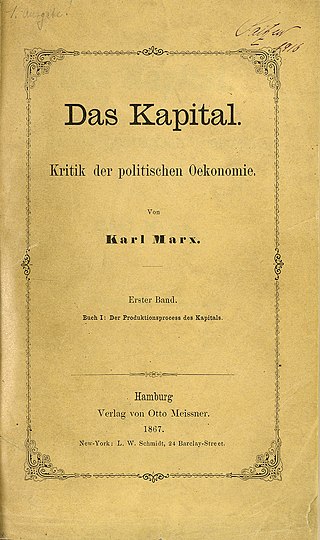

Capital. A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I: The Process of Production of Capital is the first of three treatises that make up Das Kapital, a critique of political economy by the German philosopher and economist Karl Marx. First published on 14 September 1867, Volume I was the product of a decade of research and redrafting and is the only part of Das Kapital to be completed during Marx's life. It focuses on the aspect of capitalism that Marx refers to as the capitalist mode of production or how capitalism organises society to produce goods and services.

The spectacle is a central notion in the Situationist theory, developed by Guy Debord in his 1967 book The Society of the Spectacle. In the general sense, the spectacle refers to "the autocratic reign of the market economy which had acceded to an irresponsible sovereignty, and the totality of new techniques of government which accompanied this reign." It also exists in a more limited sense, where spectacle means the mass media, which are "its most glaring superficial manifestation."

Criticisms of the labor theory of value affect the historical concept of labor theory of value (LTV) which spans classical economics, liberal economics, Marxian economics, neo-Marxian economics, and anarchist economics. As an economic theory of value, LTV is widely attributed to Marx and Marxian economics despite Marx himself pointing out the contradictions of the theory, because Marx drew ideas from LTV and related them to the concepts of labour exploitation and surplus value; the theory itself was developed by Adam Smith and David Ricardo. LTV criticisms therefore often appear in the context of economic criticism, not only for the microeconomic theory of Marx but also for Marxism, according to which the working class is exploited under capitalism, while little to no focus is placed on those responsible for developing the theory.

In Marxist philosophy, reification is the "conversion of the subject to an object, as when the worker becomes a commodity", or the process by which human social relations are perceived as inherent attributes of the people involved in them, or attributes of some product of the relation, such as a traded commodity.

In the Marxist theory of historical materialism, a mode of production is a specific combination of the:

Exploitation is a concept defined as, in its broadest sense, one agent taking unfair advantage of another agent. When applying this to labour it denotes an unjust social relationship based on an asymmetry of power or unequal exchange of value between workers and their employers. When speaking about exploitation, there is a direct affiliation with consumption in social theory and traditionally this would label exploitation as unfairly taking advantage of another person because of their vulnerable position, giving the exploiter the power.

In Karl Marx's critique of political economy and subsequent Marxian analyses, the capitalist mode of production refers to the systems of organizing production and distribution within capitalist societies. Private money-making in various forms preceded the development of the capitalist mode of production as such. The capitalist mode of production proper, based on wage-labour and private ownership of the means of production and on industrial technology, began to grow rapidly in Western Europe from the Industrial Revolution, later extending to most of the world.

Socially necessary labour time in Marx's critique of political economy is what regulates the exchange value of commodities in trade and consequently constrains producers in their attempt to economise on labour. It does not 'guide' them, as it can only be determined after the event and is thus inaccessible to forward planning.

Capital: A Critique of Political Economy, also known as Capital, is a foundational theoretical text in materialist philosophy and critique of political economy written by Karl Marx, published as three volumes in 1867, 1885, and 1894. The culmination of his life's work, the text contains Marx's analysis of capitalism, to which he sought to apply his theory of historical materialism "to lay bare the economic laws of modern society", following from classical political economists such as Adam Smith, Jean-Baptiste Say, David Ricardo and John Stuart Mill. The text's second and third volumes were completed from Marx's notes after his death and published by his colleague Friedrich Engels. Das Kapital is the most cited book in the social sciences published before 1950.

Marxian economics, or the Marxian school of economics, is a heterodox school of political economic thought. Its foundations can be traced back to Karl Marx's critique of political economy. However, unlike critics of political economy, Marxian economists tend to accept the concept of the economy prima facie. Marxian economics comprises several different theories and includes multiple schools of thought, which are sometimes opposed to each other; in many cases Marxian analysis is used to complement, or to supplement, other economic approaches. Because one does not necessarily have to be politically Marxist to be economically Marxian, the two adjectives coexist in usage, rather than being synonymous: They share a semantic field, while also allowing both connotative and denotative differences.

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Western Marxism, which drew from various sources, and the official philosophy in the Soviet Union, which enforced a rigid reading of Marx called dialectical materialism, in particular during the 1930s. Marxist philosophy is not a strictly defined sub-field of philosophy, because the diverse influence of Marxist theory has extended into fields as varied as aesthetics, ethics, ontology, epistemology, social philosophy, political philosophy, the philosophy of science, and the philosophy of history. The key characteristics of Marxism in philosophy are its materialism and its commitment to political practice as the end goal of all thought. The theory is also about the struggles of the proletariat and their reprimand of the bourgeoisie.

In the theoretical works of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels and subsequent Marxist writers, socialization is the process of transforming the act of producing and distributing goods and services from a solitary to a social relationship and collective endeavor. With the development of capitalism, production becomes centralized in firms and increasingly mechanized in contrast to the pre-capitalist modes of production where the act of production was a largely solitary act performed by individuals. Socialization occurs due to centralization of capital in industries where there are increasing returns to scale and a deepening of the division of labor and the specialization in skills necessary for increasingly complex forms of production and value creation. Progressive socialization of the forces of production under capitalism eventually comes into conflict with the persistence of relations of production based on private property; this contradiction between socialized production and private appropriation of the social product forms the impetus for the socialization of property relations (socialism).

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Marxism:

References

- ↑ "Curriculum Vitae". 18 June 2009.

- ↑ "Jonathan Beller | Pratt Institute". www.pratt.edu. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ "Columbia College Today". www.college.columbia.edu. Retrieved 2022-06-12.

- ↑ Jonathan Beller, The Cinematic Mode of Production: Attention Economy and the Society of the Spectacle UPNE, 2006

- ↑ Cf. http://libcom.org/library/deleuze-marx-politics/4-social-factory

- ↑ Jonathan Beller, video for conference The Internet as Playground and Factor, New School for Social Research http://vimeo.com/7449081

- ↑ Jonathan Beller, video for conference The Internet as Playground and Factor, New School for Social Research http://vimeo.com/7449081