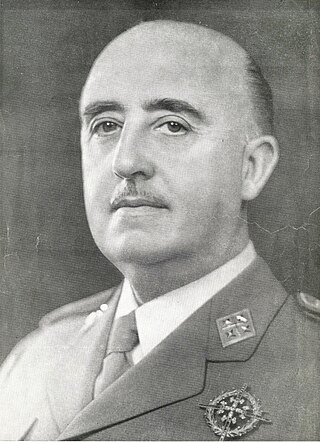

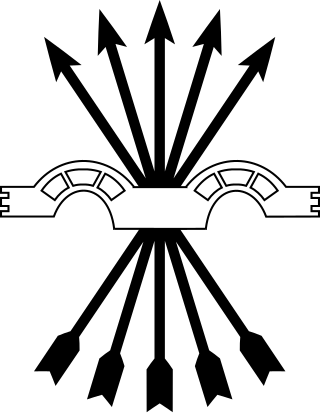

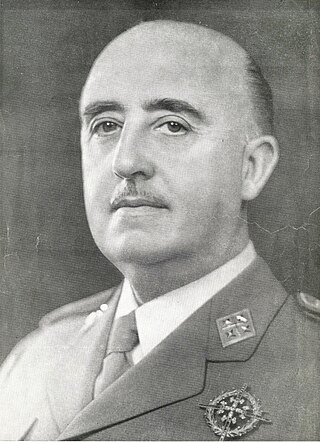

The Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista was a fascist political party founded in Spain in 1934 as merger of the Falange Española and the Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional-Sindicalista. FE de las JONS, which became the main fascist group during the Second Spanish Republic, ceased to exist as such when, during the Civil War, General Francisco Franco merged it with the Traditionalist Communion in April 1937 to form the similarly named Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las JONS.

José Antonio Primo de Rivera y Sáenz de Heredia, 1st Duke of Primo de Rivera, 3rd Marquess of Estella GE, often referred to simply as José Antonio, was a Spanish fascist politician who founded the Falange Española, later Falange Española de las JONS.

Cara al Sol is the anthem of the Falange Española de las JONS. The lyrics were written in December 1935 and are usually credited to the leader of the Falange, José Antonio Primo de Rivera. The music was composed by Juan Tellería and Juan R. Buendia.

Falangism was the political ideology of two political parties in Spain that were known as the Falange, namely first the Falange Española de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista and afterwards the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista. Falangism has a disputed relationship with fascism as some historians consider the Falange to be a fascist movement based on its fascist leanings during the early years, while others focus on its transformation into an authoritarian conservative political movement in Francoist Spain.

José Antonio Fernández de Castro was a Cuban journalist and writer active in the first part of the 20th century. He was a member of the Minorista Group, the Veterans and Patriots Movement, and participated in the Protest of the Thirteen. Every year, Cuba hosts a national journalism competition called the "José Antonio Fernández de Castro Journalism Award."

José Ignacio Rivero y Hernández was a Cuban exile and journalist.

Diario de la Marina was a newspaper published in Cuba, founded by Don Araujo de Lira in 1832. Diario de la Marina was Cuba’s longest-running newspaper. Its roots went back to 1813 with El Lucero de la Habana and the Noticioso Mercantil whose 1832 merger established El Noticioso y Lucero de la Habana, which was renamed Diario de la Marina in 1844. In 1895, Don Nicolás Rivero took over as the 13th director of the publication and transformed it into the widest-circulated newspaper in Cuba. Though a conservative publication, its pages gave voice to a wide range of opinions, including those of avowed communists. It gave a platform to essayist Jorge Mañach and many other distinguished Cuban intellectuals.

José Enrique Varela Iglesias, 1st Marquis of San Fernando de Varela was a Spanish military officer noted for his role as a Nationalist commander in the Spanish Civil War.

The Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista, frequently shortened to just "FET", was the sole legal party of the Francoist regime in Spain. It was created by General Francisco Franco in 1937 as a merger of the fascist Falange Española de las JONS with the monarchist neo-absolutist and integralist Catholic Traditionalist Communion belonging to the Carlist movement. In addition to the resemblance of names, the party formally retained most of the platform of FE de las JONS and a similar inner structure. In force until April 1977, it was rebranded as the Movimiento Nacional in 1958.

Falangism in Latin America has been a feature of political life since the 1930s as movements looked to the national syndicalist clerical fascism of the Spanish state and sought to apply it to other Spanish-speaking countries. From the mid-1930s, the Falange Exterior, effectively an overseas version of the Spanish Falange, was active throughout Latin America in order to drum up support among Hispanic communities. However, the ideas would soon permeate into indigenous political groups. The term "Falangism" should not be applied to the military dictatorships of such figures as Alfredo Stroessner, Augusto Pinochet and Rafael Trujillo because while these individuals often enjoyed close relations to Francisco Franco's Spain, their military nature and frequent lack of commitment to national syndicalism and the corporate state mean that they should not be classed as Falangist. The phenomenon can be seen in a number of movements both past and present.

The Nationalist faction or Rebel faction was a major faction in the Spanish Civil War of 1936 to 1939. It was composed of a variety of right-leaning political groups that supported the Spanish Coup of July 1936 against the Second Spanish Republic and Republican faction and sought to depose Manuel Azaña, including the Falange, the CEDA, and two rival monarchist claimants: the Alfonsist Renovación Española and the Carlist Traditionalist Communion. In 1937, all the groups were merged into the FET y de las JONS. After the death of the faction's early leaders, General Francisco Franco, one of the members of the 1936 coup, headed the Nationalists throughout most of the war, and emerged as the dictator of Spain until his death in 1975.

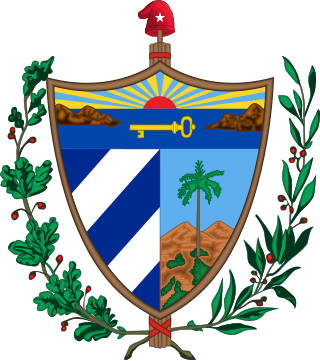

General elections were held in Cuba on 3 November 1958. The three major presidential candidates were Carlos Márquez Sterling of the Partido del Pueblo Libre, Ramón Grau of the Partido Auténtico and Andrés Rivero Agüero of the Coalición Progresista Nacional. There was also a minor party candidate on the ballot, Alberto Salas Amaro for Partido Union Cubana, who received 1% of the vote. Voter turnout was estimated at 50% of eligible voters. Although Andrés Rivero Agüero won the presidential election with 70% of the vote, he and all other elected officials were unable to take office due to the Cuban Revolution. Anselmo Alliegro y Milá briefly became the next president on 1 January 1959, before being replaced by the Chief Justice Carlos Manuel Piedra the following day, who in turn was replaced by Manuel Urrutia Lleó a day later.

The National Council of the Movement, was an institution of the Franco dictatorship of a collegiate nature, which was subordinated to the Head of State. Originally created under the name of the National Council of FET and the JONS on 19 October 1937 in the midst of the Civil War, it would continue to exist until 1977, following the death of Francisco Franco and the dismantling of institutions of his regime.

Rafael García Serrano was a Spanish writer and journalist who held a Falangist ideology. As a teenager he joined the Spanish Falange and participated as a combatant on the Nationalist side in the Spanish Civil War.

The Unification Decree was a political measure adopted by Francisco Franco in his capacity of Head of State of Nationalist Spain on April 19, 1937. The decree merged two existing political groupings, the Falangists and the Carlists, into a new party - the Falange Española Tradicionalista y de las Juntas de Ofensiva Nacional Sindicalista. As all other parties were declared dissolved at the same time, the FET became the only legal party in Nationalist Spain. It was defined in the decree as a link between state and society and was intended to form the basis for an eventual totalitarian regime. The head of state – Franco himself – was proclaimed party leader, to be assisted by the Junta Política and Consejo Nacional. A set of decrees which followed shortly after appointed members to the new executive.

Carlo-francoism was a branch of Carlism which actively engaged in the regime of Francisco Franco. Though mainstream Carlism retained an independent stand, many Carlist militants on their own assumed various roles in the Francoist system, e.g. as members of the FET y de las JONS executive, Cortes procuradores, or civil governors. The Traditionalist political faction of the Francoist regime issued from Carlism particularly held tight control over the Ministry of Justice. They have never formed an organized structure, their dynastical allegiances remained heterogeneous and their specific political objectives might have differed. Within the Francoist power strata, the carlo-francoists remained a minority faction that controlled some 5% of key posts; they failed to shape the regime and at best served as counter-balance to other groupings competing for power.

Agustín Acosta y Bello (1886-1979) was a Cuban poet, essayist, writer and politician. Acosta is considered by historians to be one of the most important Cuban writers of the twentieth century, and one of the three most important poets in the entire history of Cuba. Acosta was a revolutionary activist, and his poetry reflected his Cuban nationalism. He was both the National Poet of Cuba and also one of its Senators, when the Republic still existed. He won awards for his poetry, but also spent time as a political prisoner for criticizing the Cuban President. He lambasted the hegemonic powers of the United States in the Caribbean, but also went into exile there in the last years of his life.

Count Nicolás Lino del Rivero Fernández y Muñiz Cueli was a Spanish noble, made the 1st Count of Rivero by Alfonso XIII. He was a Carlist guerrilla fighter who, after his failure in the Carlist Wars, was forcibly expelled from Spain. He did not remain away for long, sneaking back into Spain and eventually rising to the rank of Comandante and participating in the Battle of Montejurra. However, he soon returned to Cuba where he was made an editor of Diario de la Marina, the oldest newspaper in Spanish colonial America, by the newspaper's creator. He was then promoted to become the newspaper's 13th Director, and transformed it into one of the most important newspapers in the history of Cuba, obtaining the unofficial title of Decano de a Presna .

Nicolás Rivero y Alonso was a Cuban journalist and diplomat. In 1909, he was a Cuban consular to Marseille. In 1910, he became the inspector of consulates and administrator of the National Bank of Cuba. In 1919, after his father - Nicolás Rivero y Muñiz - was posthumously granted the title of the 1st Count of Rivero, Rivero automatically became the 2nd Count of Rivero. Rivero also became the Administrator of his father's newspaper, Diario de la Marina, for a time. In 1929, Rivero was appointed the position of Honorary Consul General of Hungary to Havana. His brother was José Ignacio Rivero Alonso who became the director of Diario de la Marina while Nicolás Rivero pursued the life of Cuban diplomacy. In 1935, Rivero became the first Cuban ambassador to the Holy See. While serving in this post, Rivero lived in Rome, at the official residence of the ambassador next to the Holy See. He also served, while living in Rome, as the 3rd Cuban ambassador to Austria.

Elicio Argüelles y Pozo was a Cuban Senator and President of the Senate. During the Spanish Civil War, he was the president of the Comité Nacionalista Español (CNE), a Cuban organization dedicated to the Carlist and Falangist ideologies of the Nationalist faction. At the conclusion of the war, he was awarded the Grand Cross of the Order of Isabella the Catholic by Francisco Franco for his services to Spain. The historian Allan Chase writes that Argüelles was a blue-blood landowner who was in charge of the CNE cell "A-1," alongside his friend José Ignacio Rivero Alonso, who headed the cell "R-1." Argüelles and his son, Elicio Argüelles II, were good family friends of Ernest Hemingway, and met him at a Jai alai game. Argüelles owned the Frontón Jai Alai, the largest Jai Alai arena in Hanava.