Saint Julian Sabas, H.

Saint Julian Sabas was a man of humble origin, and with small education; but so greatly was he enlightened by the Holy Spirit, that Saint Jerome assures us he was scarcely inferior to Saint Antony and Saint Paul the first hermit; and Saint John Chrysostom, when desiring to give an example of a perfect Christian, names only Saint Julian Sabas.

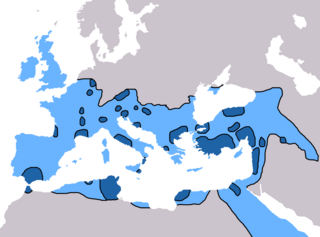

The desire to serve God in all freedom decided Julian to seek perfect solitude. He at first inhabited a cabin at the outskirts of the deserts of Osrhoene, in Mesopotamia, of which province Edessa was the capital. He ate only once a week, bread made of millet, with some salt, and drank only just sufficient water to keep him alive. Towards the end of his days he added a few figs. His time was occupied in prayer and chanting psalms. The fame of his virtue attracted disciples. Their number was at first ten, then there were twenty, and in the end as many as a hundred.

He had deserted his cabin, and had chosen as his place of abode a damp cavern; but this was so unhealthy that his disciples urged him to suffer them to live in a cabin they would erect outside. He refused his consent at first, but finally yielded to their solicitations, finding that it was impossible to preserve the bread and vegetables they ate in his cave, where they became mildewed after a night or two.

This singular community rose at midnight, and sang psalms in the cavern till the sun rose; then they went forth into the desert, two and two, and while one stood and chanted fifteen psalms, the other prostrated himself in adoration. Then the second rose to sing, and the first knelt. They all met again in the evening to their frugal meal, and to chant together the praises of God.

On one occasion Saint Julian was seized with a desire to visit Mount Sinai, and he started with his disciple Asterius. They took with them a sponge and a string, so that when they came to a well, they might let the sponge down into the water and bring it up saturated. They could then squeeze the sponge out into a shell, and so drink. Julian built a little cell and chapel on Sinai, and then returned to the desert of Osrhoene.

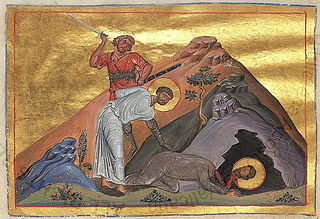

At this time Julian the Apostate was emperor, and he traversed Syria and Mesopotamia on his famous march against the Persians. Julian Sabas, fearing that the emperor, if victorious, would return to persecute the Church, spent ten days of incessant prayer to God that He would deliver the emperor into the hands of his enemies. At the end of three days he heard a voice from Heaven, which said, “Be of good cheer, that vile stinking pig is dead.” Then rejoining his companions, he bade them sing songs of rejoicing to God, who had given victory to the fire-worshiping Persians, and by the overthrow of Julian and the Roman army had dealt a death blow to the empire.

When Valens, the Arian, succeeded Jovian, Julian Sabas was summoned from his retreat to encourage the Catholics of Antioch. His words, his appearance, his miracles, mightily supported them under adversity. A curious story is told of his journey to Antioch. He entered the house of a pious woman, and asked for refreshment. She hasted eagerly to provide the saint with dinner. As she was busy, a servant rushed up to her with dismay, to say that her child, aged seven, had tumbled into the well. “Never mind, put the lid on, and get dinner ready,” said the mistress. The servant put the cover on the well, and prepared the table for the meal. After dinner Julian Sabas asked for the child, that he might bless it. “He is at the bottom of the well,” said the mother, “and we have been so busy getting dinner ready, that we have not had time to pull him out.”

Saint Julian at once went to the well, the lid was taken off, and the mischievous urchin, who was amusing himself with paddling in the water and stirring up the mud, was hauled out, and dismissed to dry his clothes, with the blessing of the hermit. Popular rumour deepened the well from a shallow tank into a profound gulf, and converted a very simple incident into an astounding miracle.

On his way home from Antioch, Saint Julian passed through Cyrus, where the emperor had placed an Arian bishop, named Asterius. The orthodox implored the assistance of the hermit, and he prayed with such ardour that the bishop fell ill, and died the day after Julian left Cyrus. In 372, when Julian Sabas was at Antioch he was very old; he had been a hermit for forty years, and in all that time he had not seen a woman’s face. The year of his death is not known with certainty, but it must have been about 378.