Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing, anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarian political philosophy within the socialist movement which rejects the state's control of the economy under state socialism. Overlapping with anarchism and libertarianism, libertarian socialists criticize wage slavery relationships within the workplace, emphasizing workers' self-management and decentralized structures of political organization. As a broad socialist tradition and movement, libertarian socialism includes anarchist, Marxist, and anarchist- or Marxist-inspired thought and other left-libertarian tendencies.

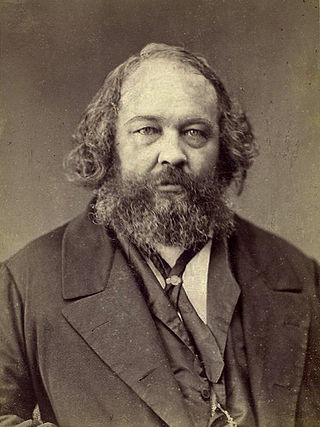

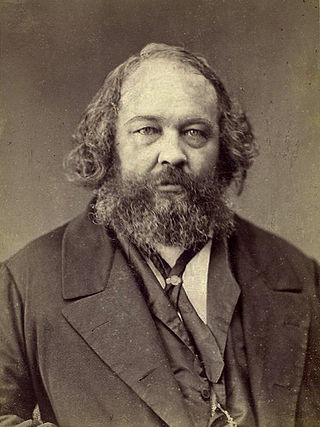

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was a Russian revolutionary anarchist, socialist and founder of collectivist anarchism. He is considered among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major founder of the revolutionary socialist and social anarchist tradition. Bakunin's prestige as a revolutionary also made him one of the most famous ideologues in Europe, gaining substantial influence among radicals throughout Russia and Europe.

The Hague Congress was the fifth congress of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), held from 2–7 September 1872 in The Hague, the Netherlands.

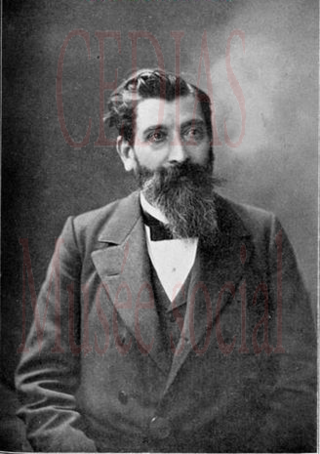

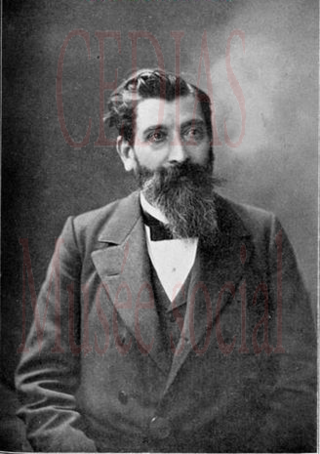

James Guillaume was a leading member of the Jura federation, the anarchist wing of the First International. Later, Guillaume would take an active role in the founding of the Anarchist St. Imier International.

The Anarchist International of St. Imier was an international workers' organization formed in 1872 after the split in the First International between the anarchists and the Marxists. This followed the 'expulsions' of Mikhail Bakunin and James Guillaume from the First International at the Hague Congress. It attracted some affiliates of the First International, repudiated the Hague resolutions, and adopted a Bakuninist programme, and lasted until 1877.

The International Alliance of Socialist Democracy was an organisation founded by Mikhail Bakunin along with 79 other members on October 28, 1868, as an organisation within the International Workingmen's Association (IWA). The establishment of the Alliance as a section of the IWA was not accepted by the general council of the IWA because, according to the IWA statutes, international organisations were not allowed to join, since the IWA already fulfilled the role of an international organisation. The Alliance dissolved shortly afterwards and the former members instead joined their respective national sections of the IWA.

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who grew up during the Restoration and was the first self-described anarchist. French anarchists fought in the Spanish Civil War as volunteers in the International Brigades. According to journalist Brian Doherty, "The number of people who subscribed to the anarchist movement's many publications was in the tens of thousands in France alone."

Anarchism is generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful as well as opposing authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Proponents of anarchism, known as anarchists, advocate stateless societies based on non-hierarchical voluntary associations. While anarchism holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, opposition to the state is not its central or sole definition. Anarchism can entail opposing authority or hierarchy in the conduct of all human relations.

Paul Brousse was a French socialist, leader of the possibilistes group. He was active in the Jura Federation, a section of the International Working Men's Association (IWMA), from the northwestern part of Switzerland and the Alsace. He helped edit the Bulletin de la Fédération Jurassienne, along with anarchist Peter Kropotkin. He was in contact with Gustave Brocher between 1877 and 1880, who became anarchist under Brousse's influence. Paul Brousse edited two newspapers, one in French and another in German. He helped James Guillaume publish its bulletin.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to anarchism, generally defined as the political philosophy which holds the state to be undesirable, unnecessary and harmful, or alternatively as opposing authority and hierarchical organization in the conduct of human relations. Proponents of anarchism, known as anarchists, advocate stateless societies or non-hierarchical voluntary associations.

Black Flame: The Revolutionary Class Politics of Anarchism and Syndicalism is a book written by Lucien van der Walt and Michael Schmidt which deals with “the ideas, history and relevance of the broad anarchist tradition through a survey of 150 years of global history.”

Over the past 150 years, anarchists, anarcho-syndicalists and libertarian socialists have held many congresses, conferences and international meetings in which trade unions, other groups and individuals have participated.

The International Workingmen's Association (IWA), often called the First International (1864–1876), was an international organisation which aimed at uniting a variety of different left-wing socialist, communist and anarchist groups and trade unions that were based on the working class and class struggle. It was founded in 1864 in a workmen's meeting held in St. Martin's Hall, London. Its first congress was held in 1866 in Geneva.

Collectivist anarchism, also called anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates the abolition of both the state and private ownership of the means of production. In their place, it envisions both the collective ownership of the means of production and the entitlement of workers to the fruits of their own labour, which would be ensured by a societal pact between individuals and collectives. Collectivists considered trade unions to be the means through which to bring about collectivism through a social revolution, where they would form the nucleus for a post-capitalist society.

Severino Albarracín Broseta (1851–1878) was a Spanish anarchist. Trained as a teacher, he became a leader of the Spanish Regional Federation of the First International and was a prominent participant in the 1873 Petroleum Revolution general strike in Alcoy. Exiled in Switzerland, he participated in the Jura Federation, where he remained an insurrectionist while working as a laborer. He returned to Spain after several years, where he died of tuberculosis.

Anarchism and libertarianism, as broad political ideologies with manifold historical and contemporary meanings, have contested definitions. Their adherents have a pluralistic and overlapping tradition that makes precise definition of the political ideology difficult or impossible, compounded by a lack of common features, differing priorities of subgroups, lack of academic acceptance, and contentious, historical usage.

The St. Imier Congress was a meeting of the Jura Federation and anti-authoritarian apostates of the First International in September 1872.

The Spanish Regional Federation of the International Workingmen's Association, known by its Spanish abbreviation FRE-AIT, was the Spanish chapter of the socialist working class organization commonly known today as the First International. The FRE-AIT was active between 1870 and 1881 and was influential not only in the labour movement of Spain, but also in the emerging global anarchist school of thought.

The Sonvilier Circular is a 1871 anti-authoritarian treatise by the Jura Federation, a breakaway faction of the First International. Written during their Sonvilier congress, it claimed that hierarchical politics could not produce social revolution, and that authoritarian organization would never produce an egalitarian society. Rather than form political parties, revolutionary organizations had to model the revolutionary society in miniature.

Anarchism in Switzerland appeared, as a political current, within the Jura Federation of the International Workingmen's Association (IWA), under the influence of Mikhail Bakunin and Swiss libertarian activists such as James Guillaume and Adhémar Schwitzguébel. Swiss anarchism subsequently evolved alongside the nascent social democratic movement and participated in the local opposition to fascism during the interwar period. The contemporary Swiss anarchist movement then grew into a number of militant groups, libertarian socialist organizations and squats.