The King's role in the independence of the Belgian Congo

In the early 1950s, political emancipation of the Congolese elites, let alone of the masses, seemed like a distant event. But, it was clear that the Congo could not forever remain immune from the rapid changes that, after the Second World War, profoundly affected colonialism around the world. The independence of the British, French and Dutch colonies in Asia shortly after 1945 had little immediate effect in the Congo, but in the United Nations pressure on Belgium (as on other colonial powers) increased. Belgium had ratified article 73 of the United Nations Charter, which advocated self-determination, and both superpowers put pressure on Belgium to reform its Congo policy. However, the Belgian government tried to resist what it described as 'interference' with its colonial policy.

It became increasingly evident that the Belgian government lacked a strategic long-term vision in relation to the independence of the Belgian Congo. 'Colonial affairs' did not generate much interest or political debate in Belgium, so long as the colony seemed to be thriving and calm. A notable exception was the young King Baudouin, who had succeeded his father, King Leopold III, under dramatic circumstances in 1951, when Leopold III was forced to abdicate. [1] Baudouin took a close interest in the Belgian Congo.

On his first state visit to the Belgian Congo in 1955, King Baudouin was welcomed enthusiastically by cheering crowds of whites and blacks alike, as captured in André Cauvin's documentary film, Bwana Kitoko [ nl ]. [2] Foreign observers, such as the international correspondent of The Manchester Guardian or a Time journalist, [3] remarked that Belgian paternalism "seemed to work", and contrasted Belgium's seemingly loyal and enthusiastic colonial subjects with the restless French and British colonies. On the occasion of his visit, King Baudouin openly endorsed the Governor-General's vision of a "Belgo-Congolese community"; but, in practice, this idea progressed slowly. At the same time, divisive ideological and linguistic issues in Belgium, which heretofore had been successfully kept out of the colony's affairs, began to affect the Congo as well. These included the rise of unionism among workers, the call for public (state) schools to break the missions' monopoly on education, and the call for equal treatment in the colony of both national languages: French and Dutch. Until then, French had been promoted as the unique colonial language. The Governor-General feared that such divisive issues would undermine the authority of the colonial government in the eyes of the Congolese, while also diverting attention from the more pressing need for true emancipation.

One year before independence

While the Belgian government was debating a programme to gradually extend the political emancipation of the Congolese population, it was overtaken by events. On 4 January 1959, a prohibited political demonstration organised in Léopoldville by ABAKO got out of hand. At once, the colonial capital was in the grip of extensive rioting. It took the authorities several days to restore order and, by the most conservative count, several hundred died. The eruption of violence sent a shock-wave through the Congo and Belgium alike. [4] On 13 January, King Baudouin addressed the nation by radio and declared that Belgium would work towards the full independence of the Congo "without delay, but also without irresponsible rashness". [5]

Without committing to a specific date for independence, the government of prime minister Gaston Eyskens had a multi-year transition period in mind. They thought provincial elections would take place in December 1959, national elections in 1960 or 1961, after which administrative and political responsibilities would be gradually transferred to the Congolese, in a process presumably to be completed towards the mid-1960s. On the ground, circumstances were changing much more rapidly. [6] Increasingly, the colonial administration saw varied forms of resistance, such as refusal to pay taxes. In some regions anarchy threatened. [7] At the same time many Belgians resident in the Congo opposed independence, feeling betrayed by Brussels. Faced with a radicalisation of Congolese demands, the government saw the chances of a gradual and carefully planned transition dwindling rapidly.

King Baudouin's speech

King Baudouin addressed the nation, during a radio speech on 13 January 1959, on the road to independence of the Belgian-Congo.

Full Speech (translated to English)

The ultimate goal of our actions is, in prosperity and peace, to assist the Congolese people on their path to independence, without delay, but also without irresponsible rashness.

In a civilized world, the independence of a nation symbolizes, combines and guarantees the values of freedom, order and prosperity.

This goal however, can not be achieved without the following premises:

strong and fair governmental institutions;

a sufficient number of experienced government officials and clerks;

a solid social, economic and financial organization, in the hands of experts in these fields;

a broad intellectual and moral education of the people, without which, a democratic system will only be an excuse for ridicule, deception and oppression of the many by the few.

We aim to create these conditions, which are at the basis of true independence, with the utmost care, in a friendly and passionate cooperation, together with our African citizens.

It is not our intention to force European solutions onto the African peoples. On the contrary, we wish to promote the development of pragmatic policies and solutions, based on the African culture, that answer to the needs of the people. [8]

Events following the King's speech

In 1959, King Baudouin made another visit to the Belgian Congo, finding a great contrast with his visit of four years before. Upon his arrival in Léopoldville, he was pelted with rocks by black Belgo-Congolese citizens who were angry with the imprisonment of Patrice Lumumba, convicted of incitement against the colonial government. Though Baudouin's reception in other cities was considerably better, the shouts of "Vive le roi!" were often followed by "Indépendance immédiate!"

The Belgian government wanted to avoid being drawn into a futile and potentially very bloody colonial war, as had happened to France in Indochina and Algeria, or to the Netherlands in Indonesia. For that reason, it was inclined to give in to the demands for immediate independence voiced by the Congolese leaders. Despite lack of preparation and an insufficient number of educated elite (mainly in the fields of economics, law and military science), the Belgian leaders hoped that things might work out. This became known as "Le Pari Congolais"—the Congolese bet.

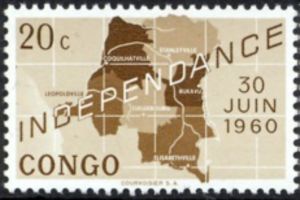

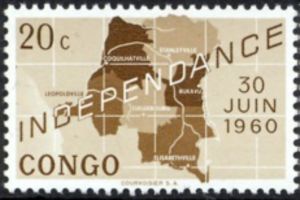

In January 1960, Congolese political leaders were invited to Brussels to participate in the Belgo-Congolese Round Table Conference to discuss independence. [9] Patrice Lumumba was discharged from prison and joined the negotiations in Brussels. In response to the strong united front put up by the Congolese delegation, the conference agreed to grant the Congolese practically all of their demands: a general election to be held in May 1960 and full independence—"Dipenda"—on 30 June 1960. [10]

Patrice Émery Lumumba, born Isaïe Tasumbu Tawosa, was a Congolese politician and independence leader who served as the first prime minister of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from June until September 1960, following the May 1960 election. He was the leader of the Congolese National Movement (MNC) from 1958 until his execution in January 1961. Ideologically an African nationalist and pan-Africanist, he played a significant role in the transformation of the Congo from a colony of Belgium into an independent republic.

The Belgian Congo was a Belgian colony in Central Africa from 1908 until independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo (Léopoldville). The former colony adopted its present name, the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), in 1964.

Baudouin was King of the Belgians from 17 July 1951 until his death in 1993. He was the last Belgian king to be sovereign of the Congo, before it became independent in 1960 and became the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Joseph Kasa-Vubu, alternatively Joseph Kasavubu, was a Congolese politician who served as the first President of the Democratic Republic of the Congo from 1960 until 1965.

The Congo Crisis was a period of political upheaval and conflict between 1960 and 1965 in the Republic of the Congo. The crisis began almost immediately after the Congo became independent from Belgium and ended, unofficially, with the entire country under the rule of Joseph-Désiré Mobutu. Constituting a series of civil wars, the Congo Crisis was also a proxy conflict in the Cold War, in which the Soviet Union and the United States supported opposing factions. Around 100,000 people are believed to have been killed during the crisis.

Pierre Ryckmans, was a Belgian civil servant who served as Governor-General of Belgium's principal African colony, the Belgian Congo, between 1934 and 1946. Ryckmans began his career in the colonial service in 1915 and also spent time in the Belgian mandate of Ruanda-Urundi. His term as Governor-General of the Belgian Congo coincided with World War II in which he was instrumental in bringing the colony into the war on the Allied side after Belgium's defeat in May 1940. He was also a prolific writer on colonial affairs. He was posthumously created a peer of the realm in the Belgian nobility with the rank of count in 1962.

Albert Kalonji was a Congolese politician and businessman from the Luba ya Kasai nobility. He was elected emperor (Mulopwe) of the Baluba ya Kasai(Bambo) and later became king of the Federated State of South Kasai.

Ambroise Boimbo was a Congolese citizen who snatched the ceremonial sword of King Baudouin I of Belgium on June 29, 1960, in Léopoldville on the eve of the independence of the Belgian Congo. He was a former soldier who originated from Monkoto, Tshuapa.

Belgium–Congo relations refers to relations between the Kingdom of Belgium and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The relationship started with the exploration of the Congo River by Henry Morton Stanley.

The Alliance of Bakongo was a Congolese political party, founded by Edmond Nzeza Nlandu, but headed by Joseph Kasa-Vubu, which emerged in the late 1950s as vocal opponent of Belgian colonial rule in what today is the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Additionally, the organization served as the major ethno-religious organization for the Kongo people and became closely intertwined with the Kimbanguist Church which was extremely popular in the lower Congo.

"Indépendance Cha Cha" was a song performed by Joseph Kabasele from the group L'African Jazz in the popular Congolese rumba style. The song has been described as "Kabasele's most memorable song" and one of the first Pan-African hits.

The Belgo-Congolese Round Table Conference was a meeting organized in two parts in 1960 in Brussels between on the one side representatives of the Congolese political class and chiefs and on the other side Belgian political and business leaders. The round table meetings led to the adoption of sixteen resolutions on the future of the Belgian Congo and its institutional reforms. With a broad consensus, the date for independence was set on June 30, 1960.

The Speech at the Ceremony of the Proclamation of the Congo's Independence was a short political speech given by Patrice Lumumba on 30 June 1960 at the ceremonies marking the independence of the Republic of Congo from Belgium. It is best known for its outspoken criticism of colonialism.

Émile Robert Alphonse Hippolyte Janssens was a Belgian military officer and colonial official, best known for his command of the Force Publique at the start of the Congo Crisis. He described himself as the "Little Maniac" and was a staunch disciplinarian, but his refusal to see Congolese independence as marking a change in the nature of his command has been cited as the immediate cause of the mutiny by the Force Publique in July 1960 that plunged Congo-Léopoldville into chaos and anarchy.

The involvement of the Belgian Congo in World War II began with the German invasion of Belgium in May 1940. Despite Belgium's surrender, the Congo remained in the conflict on the Allied side, administered by the Belgian government in exile.

The Léopoldville riots were an outbreak of civil disorder in Léopoldville in the Belgian Congo which took place in January 1959 and which were an important moment for the Congolese independence movement. The rioting occurred when members of the Alliance des Bakongo (ABAKO) political party were not allowed to assemble for a protest and colonial authorities reacted harshly. The exact death toll is not known, but at least 49 people were killed and total casualties may have been as high as 500. Following these riots, a round table conference was organized in Brussels to negotiate the terms of Congo's independence, The Congo received its independence on 30 June 1960, becoming the Republic of the Congo.

Jean Bolikango, later Bolikango Akpolokaka Gbukulu Nzete Nzube, was a Congolese educator, writer, and politician. He served twice as Deputy Prime Minister of the Republic of the Congo, in September 1960 and from February to August 1962. Enjoying substantial popularity among the Bangala people, he headed the Parti de l'Unité Nationale and worked as a key opposition member in Parliament in the early 1960s.

Alphonse Nguvulu Lubunda was a Congolese politician and diplomat.

Jules Gérard-Libois was a Belgian historian and writer. He notably founded and presided over the Centre for Socio-Political Research and Information, known for its series of working papers entitled Courriers hedomadaires which he created in 1958, together with Jean Ladrière, François Perin, and Jean Neuville. For years, Gérard-Libois provided commentary by the elections at the francophone Belgian public broadcaster RTBF.

Albert Delvaux Mafuta Kizola was a Congolese politician who served as Resident Minister of the Republic of the Congo in Belgium.