The Kinked-Demand curve theory is an economic theory regarding oligopoly and monopolistic competition. Kinked demand was an initial attempt to explain sticky prices.

The Kinked-Demand curve theory is an economic theory regarding oligopoly and monopolistic competition. Kinked demand was an initial attempt to explain sticky prices.

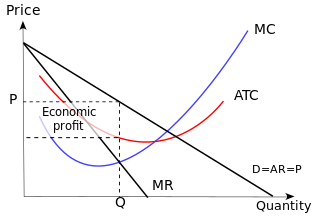

"Kinked" demand curves and traditional demand curves are similar in that they are both downward-sloping. They are distinguished by a hypothesized concave bend with a discontinuity at the bend - the "kink." Therefore, the first derivative point is undefined and leads to a jump discontinuity in the marginal revenue curve.

Classical economic theory assumes that a profit-maximizing producer with some market power (either due to oligopoly or monopolistic competition) will set marginal costs equal to marginal revenue. This idea can be envisioned graphically by the intersection of an upward-sloping marginal cost curve and a downward-sloping marginal revenue curve . In classical theory, any change in the marginal cost structure or the marginal revenue structure will be immediately reflected in a new price and/or quantity sold of the item. This result does not occur if a "kink" exists. Because of this jump discontinuity in the marginal revenue curve, marginal costs could change without necessarily changing the price or quantity.

The two seminal papers on kinked demand were written nearly simultaneously in 1939 on both sides of the Atlantic. Paul Sweezy of Harvard College published "Demand Under Conditions of Oligopoly." Sweezy argued that an ordinary demand curve does not apply to oligopoly markets and promotes a kinked demand curve.

From Queen's College in Oxford, Robert Lowe Hall and Charles J. Hitch wrote "Price Theory and Business Behavior," presenting similar ideas but including more rigorous empirical testing, including a business survey of 39 respondents in the manufacturing industry.

Hall and Hitch further present a hypothesis for the initial setting of prices; this explains why the "kink" in the curve is located where it is. They base this on a notion of "full cost" - marginal cost of each unit plus a percent of overhead costs or fixed costs with an additional percent added for profit. They emphasize the importance of industry tradition in history in determining this initial price, noting further, "An overwhelming majority of the entrepreneurs thought that a price based on full average cost…was the ‘right’ price, the one which ‘ought’ to be charged."

Others such as George Stigler have argued against kinked demand. His primary opposition is summarized in a Working Paper out of the Stanford University Economics Department by seminal authors Elmore, Kautz, Walls et al.

New classical economists, led by Chicago’s George Stigler, worked to discredit the kinked demand models. Stigler first argues that the kinked demand models are not useful, as Hall and Hitch’s model only explains observed phenomenon and is not predictive. He further explains that the kinked demand analysis only suggests why prices remain sticky and does not describe the mechanism that establishes the kink and how the kink can reform once prices change. Stigler also asserts that the model is unnecessary because Chicago theory already included allowances for short-run sticky prices due to collusion, menu costs, and regulatory or bureaucratic inefficiencies in markets.

Game theory and models of strategic interaction have largely replaced kinked demand to explain price dislocations and slowly adjusting prices. For further information see:

Microeconomics is a branch of economics that studies the behavior of individuals and firms in making decisions regarding the allocation of scarce resources and the interactions among these individuals and firms. Microeconomics focuses on the study of individual markets, sectors, or industries as opposed to the economy as a whole, which is studied in macroeconomics.

A monopoly is a market in which one person or company is the only supplier of a particular good or service. A monopoly is characterized by a lack of economic competition to produce a particular thing, a lack of viable substitute goods, and the possibility of a high monopoly price well above the seller's marginal cost that leads to a high monopoly profit. The verb monopolise or monopolize refers to the process by which a company gains the ability to raise prices or exclude competitors. In economics, a monopoly is a single seller. In law, a monopoly is a business entity that has significant market power, that is, the power to charge overly high prices, which is associated with unfair price raises. Although monopolies may be big businesses, size is not a characteristic of a monopoly. A small business may still have the power to raise prices in a small industry.

Monopolistic competition is a type of imperfect competition such that there are many producers competing against each other but selling products that are differentiated from one another and hence not perfect substitutes. In monopolistic competition, a company takes the prices charged by its rivals as given and ignores the impact of its own prices on the prices of other companies. If this happens in the presence of a coercive government, monopolistic competition will fall into government-granted monopoly. Unlike perfect competition, the company maintains spare capacity. Models of monopolistic competition are often used to model industries. Textbook examples of industries with market structures similar to monopolistic competition include restaurants, cereals, clothing, shoes, and service industries in large cities. The "founding father" of the theory of monopolistic competition is Edward Hastings Chamberlin, who wrote a pioneering book on the subject, Theory of Monopolistic Competition (1933). Joan Robinson's book The Economics of Imperfect Competition presents a comparable theme of distinguishing perfect from imperfect competition. Further work on monopolistic competition was undertaken by Dixit and Stiglitz who created the Dixit-Stiglitz model which has proved applicable used in the sub fields of international trade theory, macroeconomics and economic geography.

Neoclassical economics is an approach to economics in which the production, consumption, and valuation (pricing) of goods and services are observed as driven by the supply and demand model. According to this line of thought, the value of a good or service is determined through a hypothetical maximization of utility by income-constrained individuals and of profits by firms facing production costs and employing available information and factors of production. This approach has often been justified by appealing to rational choice theory.

An oligopoly is a market in which pricing control lies in the hands of a few sellers.

In economics, specifically general equilibrium theory, a perfect market, also known as an atomistic market, is defined by several idealizing conditions, collectively called perfect competition, or atomistic competition. In theoretical models where conditions of perfect competition hold, it has been demonstrated that a market will reach an equilibrium in which the quantity supplied for every product or service, including labor, equals the quantity demanded at the current price. This equilibrium would be a Pareto optimum.

In economics, imperfect competition refers to a situation where the characteristics of an economic market do not fulfil all the necessary conditions of a perfectly competitive market. Imperfect competition causes market inefficiencies, resulting in market failure. Imperfect competition usually describes behaviour of suppliers in a market, such that the level of competition between sellers is below the level of competition in perfectly competitive market conditions.

New Keynesian economics is a school of macroeconomics that strives to provide microeconomic foundations for Keynesian economics. It developed partly as a response to criticisms of Keynesian macroeconomics by adherents of new classical macroeconomics.

This aims to be a complete article list of economics topics:

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to industrial organization:

Francis Ysidro Edgeworth was an Anglo-Irish philosopher and political economist who made significant contributions to the methods of statistics during the 1880s. From 1891 onward, he was appointed the founding editor of The Economic Journal.

In economics, market power refers to the ability of a firm to influence the price at which it sells a product or service by manipulating either the supply or demand of the product or service to increase economic profit. In other words, market power occurs if a firm does not face a perfectly elastic demand curve and can set its price (P) above marginal cost (MC) without losing revenue. This indicates that the magnitude of market power is associated with the gap between P and MC at a firm's profit maximising level of output. The size of the gap, which encapsulates the firm's level of market dominance, is determined by the residual demand curve's form. A steeper reverse demand indicates higher earnings and more dominance in the market. Such propensities contradict perfectly competitive markets, where market participants have no market power, P = MC and firms earn zero economic profit. Market participants in perfectly competitive markets are consequently referred to as 'price takers', whereas market participants that exhibit market power are referred to as 'price makers' or 'price setters'.

Non-price competition is a marketing strategy "in which one firm tries to distinguish its product or service from competing products on the basis of attributes like design and workmanship". It often occurs in imperfectly competitive markets because it exists between two or more producers that sell goods and services at the same prices but compete to increase their respective market shares through non-price measures such as marketing schemes and greater quality. It is a form of competition that requires firms to focus on product differentiation instead of pricing strategies among competitors. Such differentiation measures allowing for firms to distinguish themselves, and their products from competitors, may include, offering superb quality of service, extensive distribution, customer focus, or any sustainable competitive advantage other than price. When price controls are not present, the set of competitive equilibria naturally correspond to the state of natural outcomes in Hatfield and Milgrom's two-sided matching with contracts model.

Bertrand competition is a model of competition used in economics, named after Joseph Louis François Bertrand (1822–1900). It describes interactions among firms (sellers) that set prices and their customers (buyers) that choose quantities at the prices set. The model was formulated in 1883 by Bertrand in a review of Antoine Augustin Cournot's book Recherches sur les Principes Mathématiques de la Théorie des Richesses (1838) in which Cournot had put forward the Cournot model. Cournot's model argued that each firm should maximise its profit by selecting a quantity level and then adjusting price level to sell that quantity. The outcome of the model equilibrium involved firms pricing above marginal cost; hence, the competitive price. In his review, Bertrand argued that each firm should instead maximise its profits by selecting a price level that undercuts its competitors' prices, when their prices exceed marginal cost. The model was not formalized by Bertrand; however, the idea was developed into a mathematical model by Francis Ysidro Edgeworth in 1889.

Cournot competition is an economic model used to describe an industry structure in which companies compete on the amount of output they will produce, which they decide on independently of each other and at the same time. It is named after Antoine Augustin Cournot (1801–1877) who was inspired by observing competition in a spring water duopoly. It has the following features:

To solve the Bertrand paradox, the Irish economist Francis Ysidro Edgeworth put forward the Edgeworth Paradox in his paper "The Pure Theory of Monopoly", published in 1897.

An Edgeworth price cycle is cyclical pattern in prices characterized by an initial jump, which is then followed by a slower decline back towards the initial level. The term was introduced by Maskin and Tirole (1988) in a theoretical setting featuring two firms bidding sequentially and where the winner captures the full market.

In economics, profit is the difference between revenue that an economic entity has received from its outputs and total costs of its inputs, also known as surplus value. It is equal to total revenue minus total cost, including both explicit and implicit costs.

Huw David Dixon is a British economist. He has been a professor at Cardiff Business School since 2006, having previously been Head of Economics at the University of York (2003–2006) after being a professor of economics there (1992–2003), and the University of Swansea (1991–1992), a Reader at Essex University (1987–1991) and a lecturer at Birkbeck College 1983–1987.

In microeconomics, the Bertrand–Edgeworth model of price-setting oligopoly looks at what happens when there is a homogeneous product where there is a limit to the output of firms which are willing and able to sell at a particular price. This differs from the Bertrand competition model where it is assumed that firms are willing and able to meet all demand. The limit to output can be considered as a physical capacity constraint which is the same at all prices, or to vary with price under other assumptions.