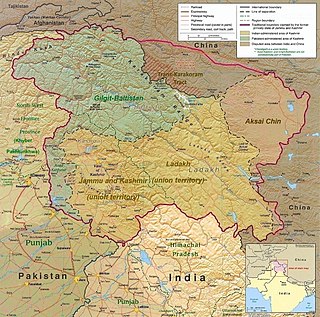

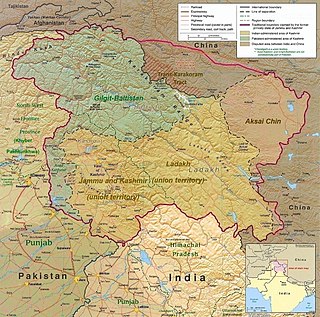

Ladakh is a region administered by India as a union territory and constitutes an eastern portion of the larger Kashmir region that has been the subject of a dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947 and India and China since 1959. Ladakh is bordered by the Tibet Autonomous Region to the east, the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh to the south, both the Indian-administered union territory of Jammu and Kashmir and the Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan to the west, and the southwest corner of Xinjiang across the Karakoram Pass in the far north. It extends from the Siachen Glacier in the Karakoram range to the north to the main Great Himalayas to the south. The eastern end, consisting of the uninhabited Aksai Chin plains, is claimed by the Indian Government as part of Ladakh, but has been under Chinese control.

Gartok is made of twin encampment settlements of Gar Günsa and Gar Yarsa in the Gar County in the Ngari Prefecture of Tibet. Gar Gunsa served as the winter encampment and Gar Yarsa as the summer encampment. But in British nomenclature, the name Gartok was applied only to Gar Yarsa and the practice continues to date.

Ladakh has a long history with evidence of human settlement from as back as 9000 b.c. It has been a crossroad of high Asia for thousands of years and has seen many cultures, empires and technologies born in its neighbours. As a result of these developments Ladakh has imported many traditions and culture from its neighbours and combining them all gave rise to a unique tradition and culture of its own.

The Suru Valley is a valley in the Kargil District in the Union Territory of Ladakh, India. It is drained by the Suru River, a tributary of the Indus River. The valley's most significant town is Sankoo.

Tingmosgang is a fortress in Temisgam village, on the bank of the Indus River in Ladakh, in northwestern India. It is 92 km west of Leh, near Khalatse, and north of the present main road. The town has a palace and the monastery over a hillock.

The Namgyal dynasty was a dynasty whose rulers were the monarchs of the former kingdom of Ladakh that lasted from 1460 to 1842 and were titled the Gyalpo of Ladakh. The Namgyal dynasty succeeded the first dynasty of Maryul and had several conflicts with the neighboring Mughal Empire and various dynasties of Tibet, including the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War. The dynasty eventually fell to the Sikh Empire and Dogras of Jammu. Most of its known history is written in the Ladakh Chronicles.

Lhachen Palgyigon was the founding king of the Kingdom of Maryul, based in modern Ladakh.

Maryul, also called mar-yul of mnga'-ris, was the western-most Tibetan kingdom based in modern-day Ladakh and some parts of Tibet. The kingdom had its capital at Shey.

The Dogra–Tibetan war or Sino-Sikh war was fought from May 1841 to August 1842, between the forces of the Dogra Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire, and those of Tibet, under the protectorate of the Qing dynasty. Gulab Singh's commander was the able general Zorawar Singh Kahluria, who, after the conquest of Ladakh, attempted to extend its boundaries in order to control the trade routes into Ladakh. Zorawar Singh's campaign, suffering from the effects of inclement weather, suffered a defeat at Taklakot (Purang) and Singh was killed. The Tibetans then advanced on Ladakh. Gulab Singh sent reinforcements under the command of his nephew Jawahir Singh. A subsequent battle near Chushul in 1842 led to a Tibetan defeat. A treaty was signed in 1842 maintaining the status quo ante bellum.

The Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal war of 1679–1684 was fought between the Central Tibetan Ganden Phodrang government, with the assistance of Mongol khanates, and the Namgyal dynasty of Ladakh with assistance from the Mughal Empire in Kashmir.

The Ganden Phodrang or Ganden Podrang was the Tibetan system of government established by the 5th Dalai Lama in 1642, when the Oirat lord Güshi Khan who founded the Khoshut Khanate conferred all spiritual and political power in Tibet to him in a ceremony in Shigatse. During the ceremony, the Dalai Lama "made a proclamation declaring that Lhasa would be the capital of Tibet and the government of would be known as Gaden Phodrang" which eventually became the seat of the Gelug school's leadership authority. The Dalai Lama chose the name of his monastic residence at Drepung Monastery for the new Tibetan government's name: Ganden (དགའ་ལྡན), the Tibetan name for Tushita heaven, which, according to Buddhist cosmology, is where the future Buddha Maitreya resides; and Phodrang (ཕོ་བྲང), a palace, hall, or dwelling. Lhasa's Red Fort again became the capital building of Tibet, and the Ganden Phodrang operated there and adjacent to the Potala Palace until 1959.

Demchok , previously called New Demchok, and called Parigas by the Chinese, is a village and military encampment in the Indian-administered Demchok sector, that is disputed between India and China. It is administered as part of the Nyoma tehsil in the Leh district of Ladakh by India, and claimed by China as part of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Tangtse or Drangtse (Tibetan: བྲང་རྩེ, Wylie: brang rtse, THL: drang tsé) is a village in the Leh district of Ladakh, India. It is located in the Durbuk tehsil. Traditionally, it was regarded as the border between the Nubra region to the north and the Pangong region to the south. It was a key halting place on the trade route between Turkestan and Tibet. It was also a site of wars between Ladakh and Tibet.

The Charding Nullah, traditionally known as the Lhari stream and called Demchok River by China, is a small river that originates near the Charding La pass that is also on the border between the two countries and flows northeast to join the Indus River near a peak called "Demchok Karpo" or "Lhari Karpo". There are villages on both sides of the mouth of the river called by the same name "Demchok", which is presumed to have been a single village originally, and has gotten split into two due to geopolitcal reasons. The river serves as the de facto border between China and India in the southern part of the Demchok sector.

The Demchok sector is a disputed area named after the villages of Demchok in Ladakh and Demchok in Tibet, situated near the confluence of the Charding Nullah and Indus River. It is a part of the greater Sino-Indian border dispute between China and India. Both China and India claim the disputed region, with a Line of Actual Control between the two nations situated along the Charding Nullah.

Demchok, was described by a British boundary commission in 1847 as a village lying on the border between the Kingdom of Ladakh and the Tibet. It was a "hamlet of half a dozen huts and tents", divided into two parts by a rivulet which formed the boundary between the two states. The rivulet, a tributary of the Indus River variously called the Demchok River, Charding Nullah, or the Lhari stream, was set as the boundary between Ladakh and Tibet in the 1684 Treaty of Tingmosgang. By 1904–05, the Tibetan side of the hamlet was said to have had 8 to 9 huts of zamindars (landholders), while the Ladakhi side had two. The area of the former Demchok now straddles the Line of Actual Control, the effective border of the People's Republic of China's Tibet Autonomous Region and the Republic of India's Ladakh Union Territory.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Ladakh:

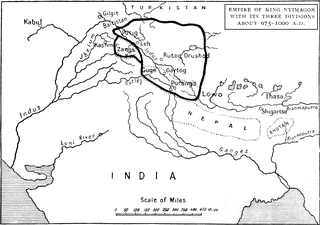

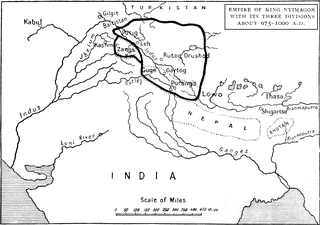

Kyide Nyimagon, whose original name was Khri-skyid-lding, was a member of the Yarlung dynasty of Tibet and a descendant of emperor Langdarma. He migrated to Western Tibet and founded the kingdom of Ngari Khorsum around 912 CE. After his death, his large kingdom was divided among his three sons, giving rise to the three kingdoms of Maryul (Ladakh), Guge-Purang and Zanskar-Spiti.

Tashigang (Tibetan: བཀྲ་ཤིས་སྒང་, Wylie: bkra shis sgang, THL: tra shi gang, transl. "auspicious hillock"), with a Chinese spelling Zhaxigang , is a village in the Gar County of the Ngari Prefecture, Tibet. The village forms the central district of the Zhaxigang Township. It houses an ancient monastery dating to the 11th century.

The Treaty of Tingmosgang, also known as the Treaty of Temisgam, was a tripartite peace agreement signed in 1684 between the Kingdom of Ladakh and the Ganden Phodrang of Tibet, with the support of the Qing dynasty, at the end of the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal war. The original text of the Treaty of Tingmosgang no longer survives, but its contents are summarized in the Ladakh Chronicles. The treaty contained clauses that established diplomatic relations, delineated borders, and regulated trade between Ladakh and Tibet.