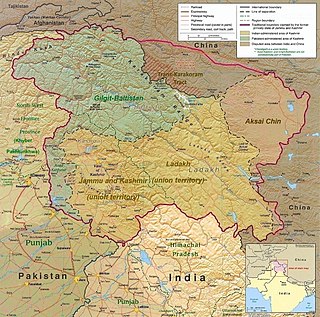

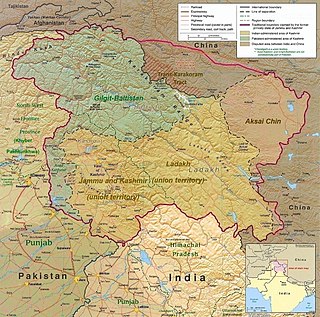

Ladakh is a region administered by India as a union territory and constitutes an eastern portion of the larger Kashmir region that has been the subject of a dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947 and India and China since 1959. Ladakh is bordered by the Tibet Autonomous Region to the east, the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh to the south, both the Indian-administered union territory of Jammu and Kashmir and the Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan to the west, and the southwest corner of Xinjiang across the Karakoram Pass in the far north. It extends from the Siachen Glacier in the Karakoram range to the north to the main Great Himalayas to the south. The eastern end, consisting of the uninhabited Aksai Chin plains, is claimed by the Indian Government as part of Ladakh, but has been under Chinese control.

Leh is a city in Indian-administered Ladakh in the disputed Kashmir region. It is the largest city and the joint capital of Ladakh. Leh, located in the Leh district, was also the historical capital of the Kingdom of Ladakh. The seat of the kingdom, Leh Palace, the former residence of the royal family of Ladakh, was built in the same style and about the same time as the Potala Palace in Tibet. Since they were both constructed in a similar style and at roughly the same time, the Potala Palace in Tibet and Leh Palace, the royal residence, are frequently contrasted. Leh is at an altitude of 3,524 m (11,562 ft), and is connected via National Highway 1 to Srinagar in the southwest and to Manali in the south via the Leh-Manali Highway.

Baltistan also known as Baltiyul or Little Tibet, is a mountainous region in the Pakistani-administered territory of Gilgit-Baltistan and constitutes a northern portion of the larger Kashmir region that has been the subject of a dispute between India and Pakistan since 1947. It is located near the Karakoram and borders Gilgit to the west, China's Xinjiang to the north, Indian-administered Ladakh to the southeast, and the Indian-administered Kashmir Valley to the southwest. The average altitude of the region is over 3,350 metres (10,990 ft). Baltistan is largely administered under the Baltistan Division.

Kargil district is a district in Indian-administered Ladakh in the disputed Kashmir-region, which is administered as a union territory of Ladakh. It is named after the city of Kargil, where the district headquarters lies. The district is bounded by the Indian-administered union territory of Jammu and Kashmir to the west, the Pakistani-administered administrative territory of Gilgit–Baltistan to the north, Ladakh's Leh district to the east, and the Indian state of Himachal Pradesh to the south. Encompassing three historical regions known as Purig, Dras and Zanskar, the district lies to the northeast of the Great Himalayas and encompasses the majority of the Zanskar Range. Its population inhabits the river valleys of the Dras, Suru, Wakha Rong, and Zanskar.

Skardu is a city located in Pakistan-administered Gilgit-Baltistan in the disputed Kashmir region. Skardu serves as the capital of Skardu District and the Baltistan Division. It is situated at an average elevation of nearly 2,500 metres above sea level in the Skardu Valley, at the confluence of the Indus and Shigar rivers. The city is an important gateway to the eight-thousanders of the nearby Karakoram mountain range. The Indus River running through the region separates the Karakoram from the Ladakh Range.

Kargil or Kargyil is a city in Indian-administered Ladakh in the Kashmir region. It is the joint capital of Ladakh, an Indian-administered union territory. It is also the headquarters of the Kargil district. It is the second-largest city in Ladakh after Leh. Kargil is located 204 kilometres (127 mi) east of Srinagar in Jammu and Kashmir, and 234 kilometres (145 mi) to the west of Leh. It is on the bank of the Suru River near its confluence with the Wakha Rong river, the latter providing the most accessible route to Leh.

The Suru Valley is a valley in the Kargil District in the Union Territory of Ladakh, India. It is drained by the Suru River, a tributary of the Indus River. The valley's most significant town is Sankoo.

Tingmosgang is a fortress in Temisgam village, on the bank of the Indus River in Ladakh, in northwestern India. It is 92 km west of Leh, near Khalatse, and north of the present main road. The town has a palace and the monastery over a hillock.

Zorawar Singh was a military general of the Dogra Rajput ruler, Gulab Singh, who served as the Raja of Jammu under the Sikh Empire. He served as the governor (wazir-e-wazarat) of Kishtwar and extended the territories of the kingdom by conquering Ladakh and Baltistan. He also boldly attempted the conquest of Western Tibet but was killed in battle of To-yo during the Dogra-Tibetan war. In reference to his legacy of conquests in the Himalaya Mountains including Ladakh, Tibet, Baltistan and Skardu as General and Wazir, Zorowar Singh has been referred to as the "Napoleon of India", and "Conqueror of Ladakh".

The Namgyal dynasty was a dynasty whose rulers were the monarchs of the former kingdom of Ladakh that lasted from 1460 to 1842 and were titled the Gyalpo of Ladakh. The Namgyal dynasty succeeded the first dynasty of Maryul and had several conflicts with the neighboring Mughal Empire and various dynasties of Tibet, including the Tibet–Ladakh–Mughal War. The dynasty eventually fell to the Sikh Empire and Dogras of Jammu. Most of its known history is written in the Ladakh Chronicles.

Maryul, also called mar-yul of mnga'-ris, was the western-most Tibetan kingdom based in modern-day Ladakh and some parts of Tibet. The kingdom had its capital at Shey.

The Dogra–Tibetan war or Sino-Sikh war was fought from May 1841 to August 1842, between the forces of the Dogra Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu, under the suzerainty of the Sikh Empire, and those of Tibet, under the protectorate of the Qing dynasty. Gulab Singh's commander was the able general Zorawar Singh Kahluria, who, after the conquest of Ladakh, attempted to extend its boundaries in order to control the trade routes into Ladakh. Zorawar Singh's campaign, suffering from the effects of inclement weather, suffered a defeat at Taklakot (Purang) and Singh was killed. The Tibetans then advanced on Ladakh. Gulab Singh sent reinforcements under the command of his nephew Jawahir Singh. A subsequent battle near Chushul in 1842 led to a Tibetan defeat. A treaty was signed in 1842 maintaining the status quo ante bellum.

Demchok , previously called New Demchok, and called Parigas by the Chinese, is a village and military encampment in the Indian-administered Demchok sector, that is disputed between India and China. It is administered as part of the Nyoma tehsil in the Leh district of Ladakh by India, and claimed by China as part of the Tibet Autonomous Region.

Tangtse or Drangtse (Tibetan: བྲང་རྩེ, Wylie: brang rtse, THL: drang tsé) is a village in the Leh district of Ladakh, India. It is located in the Durbuk tehsil. Traditionally, it was regarded as the border between the Nubra region to the north and the Pangong region to the south. It was a key halting place on the trade route between Turkestan and Tibet. It was also a site of wars between Ladakh and Tibet.

The following outline is provided as an overview of and topical guide to Ladakh:

}} Mehta Basti Ram was a Dogra officer and commander of the Fateh Shibji battalion under Raja Gulab Singh of Jammu. Basti Ram later served as the governor (thanadar) of Leh in Ladakh between 1847 and 1861. Basti Ram joined the service of Raja Gulab Singh in 1821 and became an officer under General Zorawar Singh during his conquest of Ladakh between 1834 and 1841. After holding positions such as the governor of Taklakot (briefly) and thanadar of Zanskar, he became the second governor of Leh under Maharaja Gulab Singh.

The culture of Ladakh refers to the traditional customs, belief systems, and political systems that are followed by Ladakhi people in India. The languages, religions, dance, music, architecture, food, and customs of the Ladakh region are similar to neighboring Tibet. Ladakhi is the traditional language of Ladakh. The popular dances in Ladakh include the khatok chenmo, cham, etc. The people of Ladakh also celebrate several festivals throughout the year, some of the most famous are Hemis Tsechu and Losar.

Marol is a village situated near the confluence of the Suru River and the Indus River in the Kharmang District of Baltistan, Pakistan. It is close to the India–Pakistan border (LOC).

The Dogra invasion of Ladakh was a successful military campaign led by Dogra Rajput general Zorawar Singh from August 1834 to October 1835 during the reign of Gulab Singh of Dogra dynasty against the Namgyal dynasty of Ladakh.

The Ladakh Rebellion (1835–1840) was a revolts led by former Ladakhi king Tsehpal Namgyal and the newly installed king, Moru Tadzi, against Dogra rule. Encouraged by the Sikh governor of Kashmir, the two kings, along with local leaders, attempted to overthrow the Dogra administration. They blocked trade routes, confiscated property, and imprisoned Dogra officials. General Zorawar Singh, marched into Ladakh, deposed Moru Tadzi, and reinstated Tsehpal Namgyal under strict terms of tribute. The rebellion was quelled, and Ladakh was fully annexed into the Jammu kingdom.