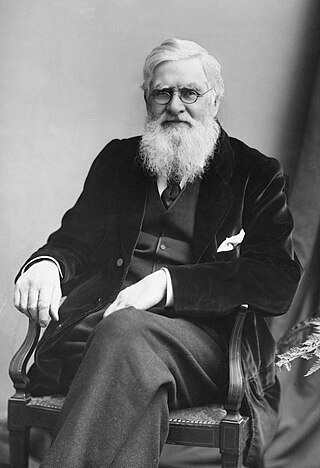

Alfred Russel Wallace was an English naturalist, explorer, geographer, anthropologist, biologist and illustrator. He independently conceived the theory of evolution through natural selection; his 1858 paper on the subject was published that year alongside extracts from Charles Darwin's earlier writings on the topic. It spurred Darwin to set aside the "big species book" he was drafting and quickly write an abstract of it, which was published in 1859 as On the Origin of Species.

David Ricardo was a British political economist, politician, and member of the Parliament of Great Britain and Ireland. He is recognized as one of the most influential classical economists, alongside figures such as Thomas Malthus, Adam Smith and James Mill.

James Mill was a Scottish historian, economist, political theorist and philosopher. He is counted among the founders of the Ricardian school of economics. He also wrote The History of British India (1817) and was one of the prominent historians to take a colonial approach. He was the first writer to divide Indian history into three parts: Hindu, Muslim and British, a classification which has proved surpassingly influential in the field of Indian historical studies.

Georgism, also called in modern times Geoism, and known historically as the single tax movement, is an economic ideology holding that people should own the value that they produce themselves, while the economic rent derived from land—including from all natural resources, the commons, and urban locations—should belong equally to all members of society. Developed from the writings of American economist and social reformer Henry George, the Georgist paradigm seeks solutions to social and ecological problems, based on principles of land rights and public finance that attempt to integrate economic efficiency with social justice.

The Radicals were a loose parliamentary political grouping in Great Britain and Ireland in the early to mid-19th century who drew on earlier ideas of radicalism and helped to transform the Whigs into the Liberal Party.

John Brown was an English Anglican priest, playwright and essayist.

Francis William Newman was an English classical scholar and moral philosopher, prolific miscellaneous writer and activist for vegetarianism and other causes.

The Coefficients was a monthly dining club founded in 1902 by the Fabian campaigners Sidney and Beatrice Webb as a forum for British socialist reformers and imperialists of the Edwardian era. The name of the dining club was a reflection of the group's focus on "efficiency".

Leopold James Maxse was an English amateur tennis player and journalist and editor of the conservative British publication, National Review, between August 1893 and his death in January 1932; he was succeeded as editor by his sister, Violet Milner. He was the son of Admiral Frederick Maxse, a Radical Liberal Unionist, who bought the National Review for him in 1893. Before the Great War, Maxse argued against liberal idealism in foreign policy, Cobdenite pacifism, Radical cosmopolitanism and, following the turn of the century, constantly warned of the 'German menace'.

The Land and Labour League was formed in October 1869 by a group of radical trade unionists affiliated to the International Working Men's Association. Its formation was precipitated by discussion of the land question at the Basle Congress of 1869. The League advocated the full nationalisation of land, and was for a brief time the centre of a working class republican network in London, with its own paper, The Republican. Despite petering out by 1873 the League had some radicalising impact on the Land Tenure Reform Association established by John Stuart Mill, which adopted a policy of taxing the unearned increment on land value under pressure from the League.

Liberalism is a political and moral philosophy based on the rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, right to private property and equality before the law. Liberals espouse various and often mutually warring views depending on their understanding of these principles but generally support private property, market economies, individual rights, liberal democracy, secularism, rule of law, economic and political freedom, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and freedom of religion, constitutional government and privacy rights. Liberalism is frequently cited as the dominant ideology of modern history.

Benjamin Lucraft was a famous craftsman chair-carver in London where his radical inclinations led him to be involved in many political movements.

Sir Charles Wentworth Dilke, 2nd Baronet was an English Liberal and Radical politician. A republican in the early 1870s, he later became a leader in the radical challenge to Whig control of the Liberal Party, making a number of important contributions, including in the legislation increasing democracy in 1883–1885, his support of the growing labour and feminist movements, and his prolific writings on international affairs.

Liberal socialism is a political philosophy that incorporates liberal principles to socialism. This synthesis sees liberalism as the political theory that takes the inner freedom of the human spirit as a given and adopts liberty as the goal, means and rule of shared human life. Socialism is seen as the method to realize this recognition of liberty through political and economic autonomy and emancipation from the grip of pressing material necessity. Liberal socialism opposes abolishing certain components of capitalism and supports something approximating a mixed economy that includes both social ownership and private property in capital goods.

Charles Alan Fyffe (1845–1892) was an English historian, who was also well known as a journalist and a political candidate.

Admiral Frederick Augustus Maxse was a British Royal Navy officer and radical liberal campaigner.

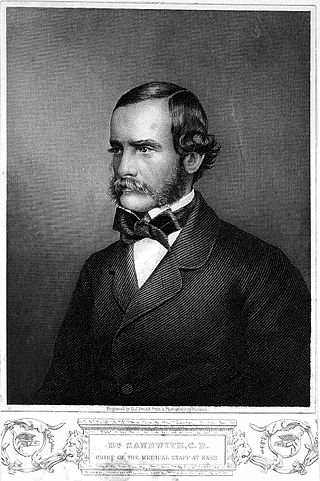

Humphry Sandwith IV was an English army physician, known also as a writer and activist.

John Hales was a British trade unionist and radical activist who served as secretary of the International Workingmen's Association.

James Beal (1829–1891) was an English land agent and auctioneer, known as a London reformer. Over many years he was a prominent radical.

Thomas Evans was a British revolutionary conspirator. Active in the 1790s and the period 1816–1820, he is otherwise a shadowy character, known mainly as a hardline follower of Thomas Spence.