Related Research Articles

Louis Marie-Anne Couperus was a Dutch novelist and poet. His oeuvre contains a wide variety of genres: lyric poetry, psychological and historical novels, novellas, short stories, fairy tales, feuilletons and sketches. Couperus is considered to be one of the foremost figures in Dutch literature. In 1923, he was awarded the Tollensprijs.

In the United States, a patroon was a landholder with manorial rights to large tracts of land in the 17th century Dutch colony of New Netherland on the east coast of North America. Through the Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions of 1629, the Dutch West India Company first started to grant this title and land to some of its invested members. These inducements to foster colonization and settlement are the basis for the patroon system. By the end of the eighteenth century, virtually all of the American states had abolished primogeniture and entail; thus patroons and manors evolved into simply large estates subject to division and leases.

The Cultivation System was a Dutch government policy from 1830–1870 for its Dutch East Indies colony. Requiring a portion of agricultural production to be devoted to export crops, it is referred to by Indonesian historians as tanam paksa.

The Vorstenlanden were four native, princely states on the island of Java in the colonial Dutch East Indies. They were nominally self-governing vassals under suzerainty of the Kingdom of the Netherlands. Their political autonomy however became increasingly constrained by severe treaties and settlements. Two of these continue to exist as a princely territory within the current independent republic of Indonesia.

Karawaci is a district of Tangerang City, Banten, Indonesia. It has an area of 13.475 km² and a population of 184,388 at the 2020 Census. Lippo Karawaci, a planned community, is located here.

Bekasi Regency is a regency of West Java Province, Indonesia. Its regency seat is in the district of Central Cikarang. It is bordered by Jakarta and by Bekasi City to the west, by Bogor Regency to the south, and by Karawang Regency to the east.

Batuceper is a district of Tangerang City, Banten, Indonesia.

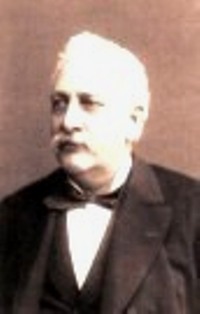

John Ricus Couperus was a Dutch lawyer, member of the Council of Justice in Padang, member of the High Military Court of the Dutch East Indies and the landheer of Tjikopo. He was also the father of the Dutch writer Louis Couperus and knight in the Order of the Netherlands Lion.

Phoa Keng Hek Sia was a Chinese Indonesian Landheer (landlord), social activist and founding president of Tiong Hoa Hwe Koan, an influential Confucian educational and social organisation meant to better the position of ethnic Chinese in the Dutch East Indies. He was also one of the founders of Institut Teknologi Bandung.

Khouw Tian Sek, Luitenant der Chinezen, popularly known as Teng Seck, was a Chinese Indonesian landlord in colonial Batavia. He is best known today as the patriarch of the prominent Khouw family of Tamboen.

Tan Liok Tiauw Sia was a prominent Chinese-Indonesian landowner, planter and industrial pioneer in the late colonial period, best known today as the last Landheer of Batoe-Tjepper, now the district of Batuceper.

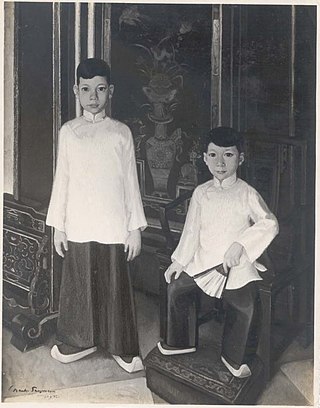

The Lauw-Sim-Zecha family is an Indonesian family of the 'Cabang Atas' or the Chinese gentry of the Dutch East Indies. They came to prominence at the start of the nineteenth century as Pachters, Landheeren (landlords) and Kapitan Cina in the colonial capital, Batavia, and in the hill station of Sukabumi, West Java. The family is of mixed Peranakan Chinese and Indo-Bohemian descent.

The Cabang Atas —literally 'highest branch' in Indonesian—was the traditional Chinese establishment or gentry of colonial Indonesia. They were the families and descendants of the Chinese officers, high-ranking colonial civil bureaucrats with the ranks of Majoor, Kapitein and Luitenant der Chinezen. They were referred to as the baba bangsawan [‘Chinese gentry’] in Indonesian, and the ba-poco in Java Hokkien.

Oei Tjie Sien was a Chinese-born colonial Indonesian tycoon and the founder of Kian Gwan, Southeast Asia's largest conglomerate at the start of the twentieth century. He is better known as the father of Oei Tiong Ham, Majoor-titulair der Chinezen (1866–1924), who modernized and vastly expanded the Oei family's business empire.

Letnan Cina Oey Thai Lo was a notable Chinese-Indonesian tycoon who acted as a pachter for tobacco in the early 19th century.

The particuliere landerijen or particuliere landen, also called tanah partikelir in Indonesian, were landed domains in a feudal system of land tenure used in parts of the Java). Dutch jurists described these domains as ‘sovereign’ and of comparable legal status to indirectly ruled Vorstenlanden [princely states] in the Indies subject to the Dutch Crown. The lord of such a domain was called a Landheer [Dutch for 'landlord'], and by law possessed landsheerlijke rechten or hak-hak ketuanan [seigniorial jurisdiction] over the inhabitants of his domain — jurisdiction exercised elsewhere by the central government.

Oey Djie San, Kapitein der Chinezen was a Chinese-Indonesian public figure, bureaucrat and landlord, best known for his role as Landheer of Karawatji and Kapitein der Chinezen of Tangerang. In the latter capacity, he headed the local Chinese civil administration in Tangerang as part of the Dutch colonial system of 'indirect rule'.

Oey Giok Koen, Kapitein der Chinezen was a Chinese-Indonesian public figure, bureaucrat and Landheer, best known for his role as Kapitein der Chinezen of Tangerang and Meester Cornelis, and as one of the richest landowners in the Dutch East Indies. As Kapitein, he headed the local Chinese civil administration in Tangerang and Meester Cornelis as part of the Dutch colonial system of 'indirect rule'. In 1893, he bought the particuliere landen or private domains of Tigaraksa and Pondok Kosambi.

Oey Khe Tay, Kapitein der Chinezen was a Chinese-Indonesian bureaucrat and landlord, best known for his role as Kapitein der Chinezen of Tangerang and Landheer of Karawatji. In the former capacity, he acted as the head of the Chinese civil administration in Tangerang as part of the Dutch colonial system of ‘indirect rule’.

Tan Tiang Po, Luitenant der Chinezen, also spelled Tan Tjeng Po, was a colonial Chinese-Indonesian bureaucrat, landowner, philanthropist and the penultimate Landheer (landlord) of the domain of Batoe-Tjepper in the Dutch East Indies.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kropveld, D. C. J. H. (1911). The Laws of Netherland East India Relating to Land: Being a Short Exposition of Their Leading Principles and Chief Provisions, and an Explanation of Dutch Terms, with Chapters on Netherland East India and Its Laws in General and on Dutch East Indian Mining Law. Stevens. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- 1 2 Anderson, Benedict Richard O'Gorman (2006). Java in a Time of Revolution: Occupation and Resistance, 1944-1946. Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-979-3780-14-6 . Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cribb, Robert (2008). Gangsters and Revolutionaries: The Jakarta People's Militia and the Indonesian Revolution, 1945-1949. Singapore: Equinox Publishing. ISBN 978-979-3780-71-9 . Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- 1 2 Creutzberg, P. (2012). Indonesia's Export Crops 1816–1940. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-011-6437-5 . Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Nola, Luthvi Febryka (November 2013). [jurnal.dpr.go.id "Sengketa Tanah Partikelir"]. Jurnal DPR RI. 4 (2): 183–196. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

{{cite journal}}: Check|url=value (help) - 1 2 3 4 Kahin, Audrey (2015). Historical Dictionary of Indonesia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-7456-5 . Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Gautama, Sudargo; Harsono, Budi (1972). Agrarian Law. Lembaga Penelitian Hukum dan Kriminologi, Universitas Padjadjaran. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Indonesia Circle. Indonesia Circle, School of Oriental and African Studies. 1996. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ Milone, Pauline Dublin (1967). "Indische Culture, and Its Relationship to Urban Life". Comparative Studies in Society and History. 9 (4): 407–426. doi:10.1017/S0010417500004618. ISSN 0010-4175. JSTOR 177686.

- ↑ Heuken, Adolf (2007). Historical Sites of Jakarta. Cipta Loka Caraka. Retrieved 15 July 2020.

- ↑ Salmon, Claudine (2006). "Women's Social Status as Reflected in Chinese Epigraphs from Insulinde (16th-20th Centuries)". Archipel. 72 (1): 157–194. doi:10.3406/arch.2006.4030.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Peratoeran baroe atas tanah-tanah particulier di tanah Djawa seblah Roelan Tjimanoek (Staatsblad 1912 No. 422). Batavia: Landsdrukkerij. 1913. p. 24.

- ↑ Almanak van Nederlandsch-Indië voor het jaar ... (in Dutch) (Vol. 44 ed.). Lands Drukkery. 1871. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ Faes, J. (1902). Over de erfpachtsrechten uitgeoefend door Chineezen en de occupatie-rechten der inlandsche bevolking, op de gronden der particuliere landerijen, ten westen der Tjimanoek (in Dutch). Buitenzorgsche drukkerij. Retrieved 18 November 2020.

- ↑ Bosma, Ulbe; Raben, Remco (2008). Being "Dutch" in the Indies: A History of Creolisation and Empire, 1500-1920. NUS Press. ISBN 978-9971-69-373-2 . Retrieved 18 November 2020.