Bohemia is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohemian kings, including Moravia and Czech Silesia, in which case the smaller region is referred to as Bohemia proper as a means of distinction.

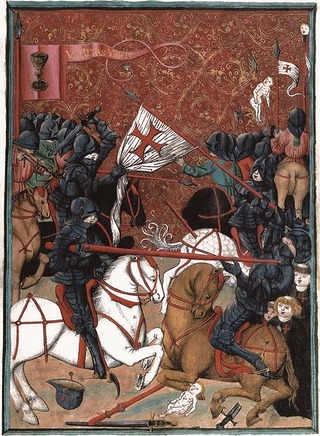

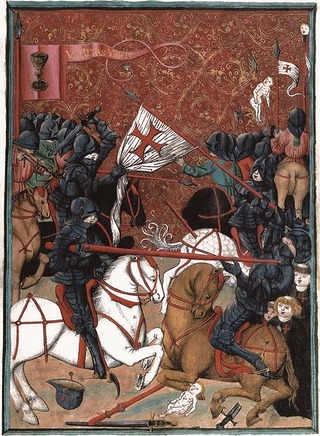

The Hussites were a Czech proto-Protestant Christian movement that followed the teachings of reformer Jan Hus, a part of the Bohemian Reformation.

The Defenestrations of Prague were three incidents in the history of Bohemia in which people were defenestrated. Though already existing in Middle French, the word defenestrate is believed to have first been used in English in reference to the episodes in Prague in 1618 when the disgruntled Protestant estates threw two royal governors and their secretary out of a window of the Hradčany Castle and wrote an extensive apologia explaining their action. In the Middle Ages and early modern times, defenestration was not uncommon—the act carried elements of lynching and mob violence in the form of murder committed together.

The history of the Czech lands – an area roughly corresponding to the present-day Czech Republic – starts approximately 800 years BCE. A simple chopper from that age was discovered at the Red Hill archeological site in Brno. Many different primitive cultures left their traces throughout the Stone Age, which lasted approximately until 2000 BCE. The most widely known culture present in the Czech lands during the pre-historical era is the Únětice Culture, leaving traces for about five centuries from the end of the Stone Age to the start of the Bronze Age. Celts – who came during the 5th century BCE – are the first people known by name. One of the Celtic tribes were the Boii (plural), who gave the Czech lands their first name Boiohaemum – Latin for the Land of Boii. Before the beginning of the Common Era the Celts were mostly pushed out by Germanic tribes. The most notable of those tribes were the Marcomanni and traces of their wars with the Roman Empire were left in south Moravia.

Ferdinand II was Holy Roman Emperor, King of Bohemia, Hungary, and Croatia from 1619 until his death in 1637. He was the son of Archduke Charles II of Inner Austria and Maria of Bavaria, who were devout Catholics. In 1590, when Ferdinand was 11 years old, they sent him to study at the Jesuits' college in Ingolstadt because they wanted to isolate him from the Lutheran nobles. A few months later, his father died, and he inherited Inner Austria–Styria, Carinthia, Carniola and smaller provinces. His cousin, Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor, who was the head of the Habsburg family, appointed regents to administer these lands.

The Battle of White Mountain was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years' War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the next three hundred years.

Frederick V was the Elector Palatine of the Rhine in the Holy Roman Empire from 1610 to 1623, and reigned as King of Bohemia from 1619 to 1620. He was forced to abdicate both roles, and the brevity of his reign in Bohemia earned him the derisive sobriquet "the Winter King".

Albrecht Wenzel Eusebius von Wallenstein, Duke of Friedland, also von Waldstein, was a Bohemian military leader and statesman who fought on the Catholic side during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648). His successful martial career made him one of the richest and most influential men in the Holy Roman Empire by the time of his death. Wallenstein became the supreme commander of the armies of the Imperial Army of Holy Roman Emperor Ferdinand II and was a major figure of the Thirty Years' War.

The Czech lands, then also known as Lands of the Bohemian Crown, were largely subject to the Habsburgs from the end of the Thirty Years' War in 1648 until the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of 1867. There were invasions by the Turks early in the period, and by the Prussians in the next century. The Habsburgs consolidated their rule and under Maria Theresa (1740–1780) adopted enlightened absolutism, with distinct institutions of the Bohemian Kingdom absorbed into centralized structures. After the Napoleonic Wars and the establishment of the Austrian Empire, a Czech National Revival began as a scholarly trend among educated Czechs, led by figures such as František Palacký. Czech nationalism took a more politically active form during the 1848 revolution, and began to come into conflict not only with the Habsburgs but with emerging German nationalism.

The House of Lobkowicz is an important Bohemian noble family that dates back to the 14th century and is one of the oldest noble families of the region. Over the centuries, the family expanded their possessions through marriage with the most powerful families of the region, which resulted in gaining vast territories all across central Europe. Due to that, the family was also incorporated into the German, Austrian and Belgian nobility.

Czech nobility consists of the noble families from historical Czech lands, especially in their narrow sense, i.e. nobility of Bohemia proper, Moravia and Austrian Silesia – whether these families originated from those countries or moved into them through the centuries. These are connected with the history of Great Moravia, Duchy of Bohemia, later Kingdom of Bohemia, Margraviate of Moravia, the Duchies of Silesia and the Crown of Bohemia, the constitutional predecessor state of the modern-day Czech Republic.

The Lands of the Bohemian Crown were the states in Central Europe during the medieval and early modern periods with feudal obligations to the Bohemian kings. The crown lands primarily consisted of the Kingdom of Bohemia, an electorate of the Holy Roman Empire according to the Golden Bull of 1356, the Margraviate of Moravia, the Duchies of Silesia, and the two Lusatias, known as the Margraviate of Upper Lusatia and the Margraviate of Lower Lusatia, as well as other territories throughout its history. This agglomeration of states nominally under the rule of the Bohemian kings was referred to simply as Bohemia. They are now sometimes referred to in scholarship as the Czech lands, a direct translation of the Czech abbreviated name.

The Kingdom of Bohemia, sometimes referenced in English literature as the Czech Kingdom, was a medieval and early modern monarchy in Central Europe. It was the predecessor state of the modern Czech Republic.

The history of Moravia, one of the Czech lands, is diverse and characterized by many periods of foreign governance.

This article covers the period from the origin of the Moravian Church, as well as the related Hussite Church and Unity of the Brethren, in the early fourteenth century to the beginning of mission work in 1732. Further expanding the article, attention will also be paid to the early Moravian settlement at Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, following their first arrival in Nazareth, Pennsylvania in 1740.

The Bohemian Revolt was an uprising of the Bohemian estates against the rule of the Habsburg dynasty that began the Thirty Years' War. It was caused by both religious and power disputes. The estates were almost entirely Protestant, mostly Utraquist Hussite but there was also a substantial German population that endorsed Lutheranism. The dispute culminated after several battles in the final Battle of White Mountain, where the estates suffered a decisive defeat. This started re-Catholisation of the Czech lands, but also expanded the scope of the Thirty Years' War by drawing Denmark and Sweden into it. The conflict spread to the rest of Europe and devastated vast areas of Central Europe, including the Czech lands, which were particularly stricken by its violent atrocities.

Kłodzko Land is a historical region in southwestern Poland.

The Margraviate of Moravia was one of the Lands of the Bohemian Crown within the Holy Roman Empire and then Austria-Hungary, existing from 1182 to 1918. It was officially administered by a margrave in cooperation with a provincial diet. It was variously a de facto independent state, and also subject to the Duchy, later the Kingdom of Bohemia. It comprised the historical region called Moravia, which lies within the present-day Czech Republic.

The Estates Revolt was the first anti-Habsburg uprising of the Czech estates, which took place in Prague in January–July 1547, and the third uprising of the estates in the Habsburg Empire after the Revolt of the Comuneros in Spain (1520–1522) and the Revolt of Ghent in Flanders (1539–1540). The uprising was triggered by the absolutist policies of King Ferdinand I of Habsburg, aimed at reducing the political influence of the privileged estates and the recatolization of the lands of the Bohemian Crown.