The Brittoniclanguages form one of the two branches of the Insular Celtic language family; the other is Goidelic. The name Brythonic was derived by Welsh Celticist John Rhys from the Welsh word Brython, meaning Ancient Britons as opposed to an Anglo-Saxon or Gael.

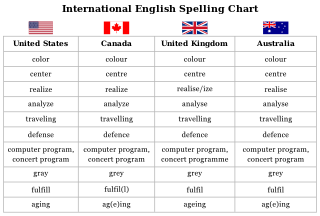

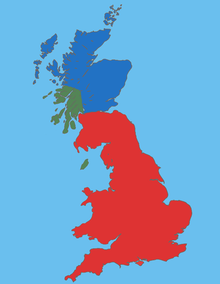

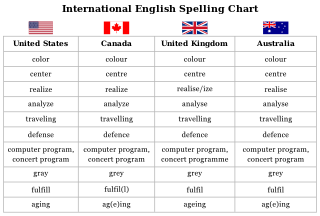

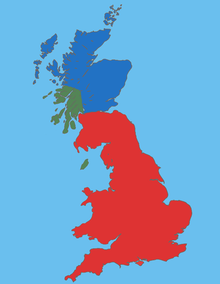

British English (BrE) is, according to Oxford Dictionaries, "English as used in Great Britain, as distinct from that used elsewhere". More narrowly, it can refer specifically to the English language in England, or, more broadly, to the collective dialects of English throughout the British Isles taken as a single umbrella variety, for instance additionally incorporating Scottish English, Welsh English, and Northern Irish English. Tom McArthur in the Oxford Guide to World English acknowledges that British English shares "all the ambiguities and tensions [with] the word 'British' and as a result can be used and interpreted in two ways, more broadly or more narrowly, within a range of blurring and ambiguity".

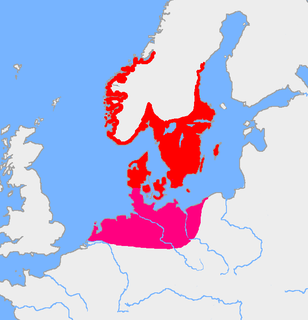

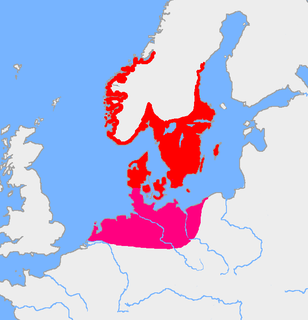

The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family spoken natively by a population of about 515 million people mainly in Europe, North America, Oceania and Southern Africa. The most widely spoken Germanic language, English, is also the world's most widely spoken language with an estimated 2 billion speakers. All Germanic languages are derived from Proto-Germanic, spoken in Iron Age Scandinavia.

Old English, or Anglo-Saxon, is the earliest recorded form of the English language, spoken in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It was brought to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the mid-5th century, and the first Old English literary works date from the mid-7th century. After the Norman conquest of 1066, English was replaced, for a time, by Anglo-Norman as the language of the upper classes. This is regarded as marking the end of the Old English era, since during this period the English language was heavily influenced by Anglo-Norman, developing into a phase known now as Middle English in England and Early Scots in Scotland.

The toponymy of England derives from a variety of linguistic origins. Many English toponyms have been corrupted and broken down over the years, due to language changes which have caused the original meanings to be lost. In some cases, words used in these place-names are derived from languages that are extinct, and of which there are no known definitions. Place-names may also be compounds composed of elements derived from two or more languages from different periods. The majority of the toponyms predate the radical changes in the English language triggered by the Norman Conquest, and some Celtic names even predate the arrival of the Anglo-Saxons in the first millennium AD.

Proto-Germanic is the reconstructed proto-language of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European languages.

English is a West Germanic language that originated from Ingvaeonic languages brought to Britain in the mid 5th to 7th centuries AD by Anglo-Saxon migrants from what is now northwest Germany, southern Denmark and the Netherlands. The Anglo-Saxons settled in the British Isles from the mid-5th century and came to dominate the bulk of southern Great Britain. Their language originated as a group of Ingvaeonic languages which were spoken by the settlers in England and southern and eastern Scotland in the early Middle Ages, displacing the Celtic languages that had previously been dominant. Old English reflected the varied origins of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms established in different parts of Britain. The Late West Saxon dialect eventually became dominant. A significant subsequent influence on the shaping of Old English came from contact with the North Germanic languages spoken by the Scandinavian Vikings who conquered and colonized parts of Britain during the 8th and 9th centuries, which led to much lexical borrowing and grammatical simplification. The Anglian dialects had a greater influence on Middle English.

The Gewisse was a tribe or clan of Anglo-Saxon England, historically assumed to have been based in the upper Thames region around Dorchester on Thames. The Gewisse are one of the direct precursors of modern-day England, being the origin of its predecessor states according to Saxon legend.

Proto-Celtic, or Common Celtic, is the ancestral proto-language of all known Celtic languages, and a descendant of Proto-Indo-European. It is not attested in writing but has been partly reconstructed through the comparative method. Proto-Celtic is generally thought to have been spoken between 1300 and 800 BC, after which it began to split into different languages. Proto-Celtic is often associated with the Urnfield culture and particularly with the Hallstatt culture. Celtic languages share common features with Italic languages that are not found in other branches of Indo-European, suggesting the possibility of an earlier Italo-Celtic linguistic unity.

The Britons, also known as Celtic Britons or Ancient Britons were the Celtic people who inhabited Great Britain from at least the British Iron Age and into the Middle Ages, at which point they diverged into the Welsh, Cornish and Bretons. They spoke the Common Brittonic language, the ancestor of the modern Brittonic languages.

Old English phonology is necessarily somewhat speculative since Old English is preserved only as a written language. Nevertheless, there is a very large corpus of the language, and the orthography apparently indicates phonological alternations quite faithfully, so it is not difficult to draw certain conclusions about the nature of Old English phonology.

Peter Schrijver is a Dutch linguist. He is a professor of Celtic languages at Utrecht University and a researcher of ancient Indo-European linguistics. He worked previously at Leiden University and the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich.

The name of London is derived from a word first attested, in Latinised form, as Londinium. By the first century CE, this was a commercial centre in Roman Britain.

British Latin or British Vulgar Latin was the Vulgar Latin spoken in Great Britain in the Roman and sub-Roman periods. While Britain formed part of the Roman Empire, Latin became the principal language of the elite, especially in the more romanized south and east of the island. However, in the less romanized north and west it never substantially replaced the Brittonic language of the indigenous Britons. In recent years, scholars have debated the extent to which British Latin was distinguishable from its continental counterparts, which developed into the Romance languages.

The Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain is the process which changed the language and culture of most of what became England from Romano-British to Germanic. The Germanic-speakers in Britain, themselves of diverse origins, eventually developed a common cultural identity as Anglo-Saxons. This process principally occurred from the mid-fifth to early seventh centuries, following the end of Roman rule in Britain around the year 410. The settlement was followed by the establishment of the Heptarchy, Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in the south and east of Britain, later followed by the rest of modern England, and the south-east of modern Scotland.

The Insular Celts were speakers of the Insular Celtic languages in the British Isles and Brittany. The term is mostly used for the Celtic peoples of the isles up until the early Middle Ages, covering the British–Irish Iron Age, Roman Britain and Sub-Roman Britain. They included the Celtic Britons, the Picts, and the Gaels.

Brittonicisms in English are the linguistic effects in English attributed to the historical influence of Brittonic speakers as they switched language to English following the Anglo-Saxon settlement of Britain and the establishment of Anglo-Saxon political dominance in Britain.

The decline of Celtic languages in England was the historical process by which the Celtic languages died out in what is modern-day England. It happened in most of southern Great Britain between about 400 and 1000 AD, but in Cornwall, it was finished only in the 18th century.

The Cornish language separated from the southwestern dialect of Common Brittonic at some point between 600 and 1000 AD. The phonological similarity of the Cornish, Welsh, and Breton languages during this period is reflected in their writing systems, and in some cases it is not possible to distinguish these languages orthographically. However, by the time it had ceased to be spoken as a community language around 1800 the Cornish language had undergone significant phonological changes, resulting in a number of unique features which distinguish it from the other neo-Brittonic languages.

The New Quantity System, or the Great British Vowel Shift, was a radical restructuring of the phonological system of the Common Brittonic language which occurred sometime after the middle of the first millennium AD, resulting in the collapse of the early Brittonic system of phonemic vowel length oppositions, which was inherited from Proto-Celtic, and its replacement by a system in which the formerly allophonic qualitative differences between long and short vowels is phonemicized, and vowel length becomes allophonic, and is determined by stress and syllable structure.