Soft-paste porcelain is a type of ceramic material in pottery, usually accepted as a type of porcelain. It is weaker than "true" hard-paste porcelain, and does not require either its high firing temperatures or special mineral ingredients. There are many types, using a range of materials. The material originated in the attempts by many European potters to replicate hard-paste Chinese export porcelain, especially in the 18th century, and the best versions match hard-paste in whiteness and translucency, but not in strength. But the look and feel of the material can be highly attractive, and it can take painted decoration very well.

Meissen porcelain or Meissen china was the first European hard-paste porcelain. Early experiments were done in 1708 by Ehrenfried Walther von Tschirnhaus. After his death that October, Johann Friedrich Böttger continued von Tschirnhaus's work and brought this type of porcelain to the market, financed by Augustus the Strong, King of Poland and Elector of Saxony. The production of porcelain in the royal factory at Meissen, near Dresden, started in 1710 and attracted artists and artisans to establish, arguably, the most famous porcelain manufacturer known throughout the world. Its signature logo, the crossed swords, was introduced in 1720 to protect its production; the mark of the swords is reportedly one of the oldest trademarks in existence.

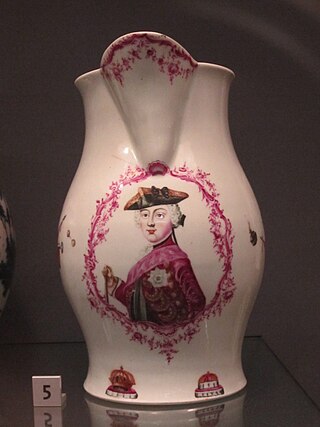

Liverpool porcelain is mostly of the soft-paste porcelain type and was produced between about 1754 and 1804 in various factories in Liverpool. Tin-glazed English delftware had been produced in Liverpool from at least 1710 at numerous potteries, but some then switched to making porcelain. A portion of the output was exported, mainly to North America and the Caribbean.

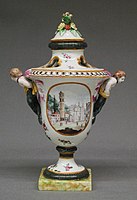

Capodimonte porcelain is porcelain created by the Capodimonte porcelain manufactory, which operated in Naples, Italy, between 1743 and 1759. Capodimonte is the most outstanding factory for early Italian porcelain, the Doccia porcelain of Florence being the other main Italian factory. Capodimonte is most famous for its moulded figurines.

William Billingsley (1758–1828) was an influential painter of porcelain in several English porcelain factories, who also developed his own recipe for soft-paste porcelain, which produced beautiful results but a very high rate of failure in firing. He is a leading name associated with the English Romantic style of paintings of groups of flowers on porcelain that is sometimes called "naturalistic" by older sources, although that may not seem its main characteristic today.

The Frankenthal Porcelain Factory was one of the greatest porcelain manufacturers of Germany and operated in Frankenthal in the Rhineland-Palatinate between 1755 and 1799. From the start they made hard-paste porcelain, and produced both figurines and dishware of very high quality, somewhat reflecting in style the French origin of the business, especially in their floral painting. Initially they were a private business, but from 1761 were owned by the local ruler, like most German porcelain factories of the period.

The Doccia porcelain manufactory, at Doccia, a frazione of Sesto Fiorentino, near Florence, was in theory founded in 1735 by marchese Carlo Ginori near his villa, though it does not appear to have produced wares for sale until 1746. It has remained the most important Italian porcelain factory ever since.

Mennecy-Villeroy porcelain is a French soft-paste porcelain from the manufactory established under the patronage of Louis-François-Anne de Neufville, duc de Villeroy (1695–1766) and — from 1748 — housed in outbuildings in the park of his château de Villeroy, and in the nearby village of Mennecy (Île-de-France). The history of the factory remains somewhat unclear, but it is typically regarded as producing between about 1738 and 1765.

The city of Nevers, Nièvre, now in the Bourgogne-Franche-Comté region in central France, was a centre for manufacturing faience, or tin-glazed earthenware pottery, between around 1580 and the early 19th century. Production of Nevers faience then gradually died down to a single factory, before a revival in the 1880s. In 2017, there were still two potteries making it in the city, after a third had closed. However the quality and prestige of the wares has gradually declined, from a fashionable luxury product for the court, to a traditional regional speciality using styles derived from the past.

The city of Rouen, Normandy has been a centre for the production of faience or tin-glazed earthenware pottery, since at least the 1540s. Unlike Nevers faience, where the earliest potters were immigrants from Italy, who at first continued to make wares in Italian maiolica styles with Italian methods, Rouen faience was essentially French in inspiration, though later influenced by East Asian porcelain. As at Nevers, a number of styles were developed and several were made at the same periods.

French porcelain has a history spanning a period from the 17th century to the present. The French were heavily involved in the early European efforts to discover the secrets of making the hard-paste porcelain known from Chinese and Japanese export porcelain. They succeeded in developing soft-paste porcelain, but Meissen porcelain was the first to make true hard-paste, around 1710, and the French took over 50 years to catch up with Meissen and the other German factories.

Rouen porcelain is soft-paste porcelain made in the city of Rouen, Normandy, France, during a brief period from about 1673 to 1696. It was the earliest French porcelain, but was probably never made on a commercial basis; only nine pieces are now thought to survive.

Real Fábrica del Buen Retiro was a porcelain manufacturing factory in Spain. It was located in Madrid's Parque del Buen Retiro, Madrid on a site near the Fuente del Ángel Caído.

Coalport, Shropshire, England was a centre of porcelain and pottery production between about 1795 and 1926, with the Coalport porcelain brand continuing to be used up to the present. The opening in 1792 of the Coalport Canal, which joins the River Severn at Coalport, had increased the attractiveness of the site, and from 1800 until a merger in 1814 there were two factories operating, one on each side of the canal, making rather similar wares which are now often difficult to tell apart.

China painting, or porcelain painting, is the decoration of glazed porcelain objects such as plates, bowls, vases or statues. The body of the object may be hard-paste porcelain, developed in China in the 7th or 8th century, or soft-paste porcelain, developed in 18th-century Europe. The broader term ceramic painting includes painted decoration on lead-glazed earthenware such as creamware or tin-glazed pottery such as maiolica or faience.

The Lowestoft Porcelain Factory was a soft-paste porcelain factory on Crown Street in Lowestoft, Suffolk, England, which was active from 1757 to 1802. It mostly produced "useful wares" such as pots, teapots, and jugs, with shapes copied from silverwork or from Bow and Worcester porcelain. The factory, built on the site of an existing pottery or brick kiln, was later used as a brewery and malt kiln. Most of its remaining buildings were demolished in 1955.

Vienna porcelain is the product of the Vienna Porcelain Manufactory, a porcelain manufacturer in Alsergrund in Vienna, Austria. It was founded in 1718 and continued until 1864.

Ludwigsburg porcelain is porcelain made at the Ludwigsburg Porcelain Manufactory founded by Charles Eugene, Duke of Württemberg, on 5 April 1758 by decree as the Herzoglich-ächte Porcelaine-Fabrique. It operated from the grounds of the Baroque Ludwigsburg Palace. After a first two decades that were artistically, but not financially, successful, the factory went into a slow decline and was closed in 1824. Much later a series of other companies used the Ludwigsburg name, but the last production was in 2010.

Vezzi porcelain is porcelain made by the Vezzi porcelain factory in Venice, Italy, established in 1720 by the Vezzi family. It was the first porcelain factory in Italy, after the experimental Medici porcelain of the 16th century. It operated only until 1727, so surviving pieces are few, probably fewer than 200. It made "true" hard-paste porcelain, and was only the third factory in Europe to do so, hiring technicians from Meissen porcelain and Vienna porcelain, the first two makers.

Cozzi porcelain is porcelain made by the Cozzi factory in Venice, which operated between 1764 and 1812. Production included sculptural figurines, mostly left in plain glazed white, and tableware, mostly painted with floral designs or with figures in landscapes and buildings, in "bright but rough" colours. They were rather derivative, drawing from Meissen porcelain in particular in the early years.