Elizabeth I was Queen of England and Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. She was the last monarch of the House of Tudor.

Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester, was an English statesman and the favourite of Elizabeth I from her accession until his death. He was a suitor for the queen's hand for many years.

Lord Guildford Dudley was an English nobleman who was married to Lady Jane Grey. She occupied the English throne from 10 July until 19 July 1553, having been declared the heir of King Edward VI. Guildford Dudley had a humanist education and married Jane in a magnificent celebration about six weeks before the King's death. After Guildford's father, the Duke of Northumberland, had engineered Jane's accession, Jane and Guildford spent her brief rule residing in the Tower of London. They were still in the Tower when their regime collapsed and remained there in different quarters as prisoners. They were condemned to death for high treason in November 1553. Queen Mary I was inclined to spare their lives, but Thomas Wyatt's rebellion against Mary's plans to marry Philip of Spain led to the young couple's execution, a measure that was widely seen as unduly harsh.

John Dudley, 2nd Earl of Warwick, KB was an English nobleman and the heir of John Dudley, 1st Duke of Northumberland, leading minister and regent under King Edward VI from 1550–1553. As his father's career progressed, John Dudley respectively assumed his father's former titles, Viscount Lisle and Earl of Warwick. Interested in the arts and sciences, he was the dedicatee of several books by eminent scholars, both during his lifetime and posthumously. His marriage to the former Protector Somerset's eldest daughter, in the presence of the King and a magnificent setting, was a gesture of reconciliation between the young couple's fathers. However, their struggle for power flared up again and ended with the Duke of Somerset's execution. In July 1553, after King Edward's death, Dudley was one of the signatories of the letters patent that attempted to set Lady Jane Grey on the throne of England, and took arms against Mary Tudor, alongside his father. The short campaign did not see any military engagements and ended as the Duke of Northumberland and his son were taken prisoners at Cambridge. John Dudley the younger was condemned to death yet reprieved. He died shortly after his release from the Tower of London.

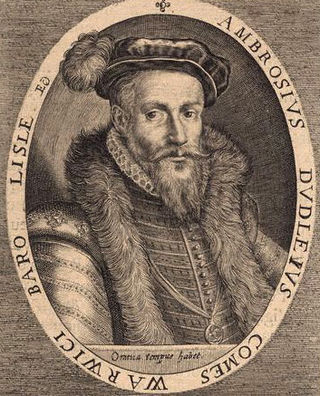

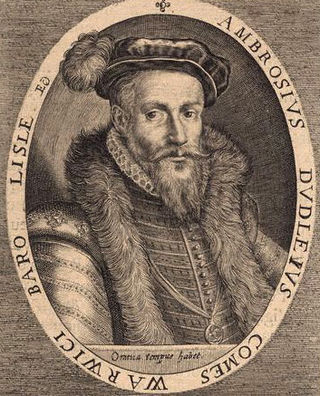

Ambrose Dudley, 3rd Earl of Warwick, KG was an English nobleman and general, and an elder brother of Queen Elizabeth I's favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Their father was John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, who led the English government from 1550–1553 under King Edward VI and unsuccessfully tried to establish Lady Jane Grey on the English throne after the King's death in July 1553. For his participation in this venture, Ambrose Dudley was imprisoned in the Tower of London and condemned to death. Reprieved, his rehabilitation came after he fought for King Philip in the Battle of St. Quentin.

Lettice Knollys, Countess of Essex and Countess of Leicester, was an English noblewoman and mother to the courtiers Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, and Lady Penelope Rich. By her second marriage to Elizabeth I's favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, she incurred the Queen's unrelenting displeasure.

Amy, Lady Dudley was the first wife of Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester, favourite of Elizabeth I of England. She is primarily known for her death by falling down a flight of stairs, the circumstances of which have often been regarded as suspicious. Amy Robsart was the only child of a substantial Norfolk gentleman. In the vernacular of the day, her name was spelled as Amye Duddley.

Douglas, Lady Sheffield, was an English noblewoman, the lover of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester and mother by him of explorer/cartographer Sir Robert Dudley, an illegitimate son.

Kenilworth. A Romance is a historical romance novel by Sir Walter Scott, one of the Waverley novels, first published on 13 January 1821. Set in 1575, it leads up to the elaborate reception of Queen Elizabeth at Kenilworth Castle by the Earl of Leicester, who is complicit in the murder of his wife Amy Robsart at Cumnor.

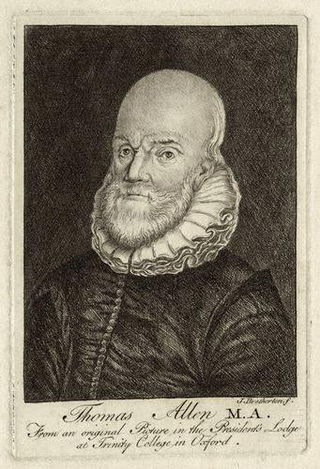

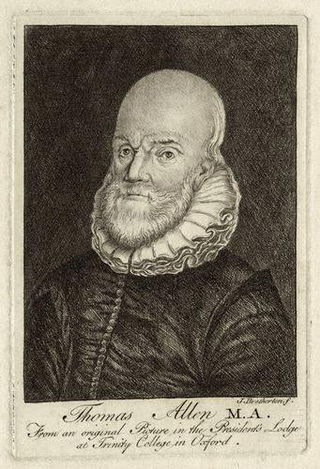

Thomas Allen (or Alleyn) (21 December 1542 – 30 September 1632) was an English mathematician and astrologer. Highly reputed in his lifetime, he published little, but was an active private teacher of mathematics. He was also well connected in the English intellectual networks of the period.

Sir Christopher Blount was an English soldier, secret agent, and rebel. He served as a leading household officer of Robert Dudley, 1st Earl of Leicester. A Catholic, Blount corresponded with Mary, Queen of Scots's Paris agent, Thomas Morgan, probably as a double agent. After the Earl of Leicester's death he married the Dowager Countess, Lettice Knollys, mother of Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex. Blount became a comrade-in-arms and confidant of the Earl of Essex and was a leading participant in the latter's rebellion in February 1601. About five weeks later he was beheaded on Tower Hill for high treason.

Sir Thomas Heneage PC was an English politician and courtier at the court of Elizabeth I.

Thomas Morgan of Llantarnam (1546–1606), of the Welsh Morgan of Monmouthshire, was a confidant and spy for Mary, Queen of Scots, and was involved in the Babington plot to kill Queen Elizabeth I of England. In his youth, Thomas, a staunch Catholic, worked as Secretary of the Archbishop of York until 1568, and then for Lord Shrewsbury who had Mary under his care at this time. Morgan's Catholic leanings soon brought him into the confidence of the Scottish queen and Mary enlisted Morgan as her secretary and go-between for the period extending between 1569 -1572 which coincided with a series of important conspiracies against Elizabeth. Morgan was imprisoned for 3 years in the Tower of London before exiling himself to France.

Katherine Hastings, Countess of Huntingdon was an English noblewoman.

Francis James Burgoyne was a British librarian and author. Born in Blaenavon, he was the Chief Librarian of Lambeth from 1887 until his death in 1913; according to an article in the South London Press, "under his care the Lambeth Libraries became the best equipped institutions of the kind in the Metropolis". An obituary in the Pall Mall Gazette said that "in addition to several authoritative works on public library administration, [he] published some important contributions to Baconian literature".

Sir Charles Arundell, was an English gentleman, lord of the manor of South Petherton, Somerset, notable as an early Roman Catholic recusant and later as a leader of the English exiles in France. He has been suggested as the author of Leicester's Commonwealth, an anonymous work which attacked Queen Elizabeth's favourite, the Earl of Leicester.

Alice Dudley, Duchess of Dudley, also known as Duchess Dudley, was the second wife of the explorer Sir Robert Dudley. In 1605, after giving birth to seven daughters, she was abandoned by her husband, who went into exile in Tuscany, remarried, and eventually sold his English estates. In 1644, by way of reparation for her losses, King Charles I created Alice Dudley a duchess in her own right "for her natural life", the dukedom thus created not being heritable.

The succession to the childless Elizabeth I was an open question from her accession in 1558 to her death in 1603, when the crown passed to James VI of Scotland. While the accession of James went smoothly, the succession had been the subject of much debate for decades. In some scholarly views, it was a major political factor of the entire reign, even if not so voiced. Separate aspects have acquired their own nomenclature: the "Norfolk conspiracy", Patrick Collinson's "Elizabethan exclusion crisis", the "Secret Correspondence", and the "Valentine Thomas affair".

Henry Dudley was an English soldier and an elder brother of Queen Elizabeth I's favourite, Robert Dudley, Earl of Leicester. Their father was John Dudley, Duke of Northumberland, who led the English government from 1550 to 1553 under Edward VI and unsuccessfully tried to establish Lady Jane Grey on the English throne after the King's death in July 1553. For his participation in this venture Henry Dudley was imprisoned in the Tower of London and condemned to death, but pardoned.

Ambrose Smith or Smythe was a London mercer in Cheapside and silkman who supplied Elizabeth I