Related Research Articles

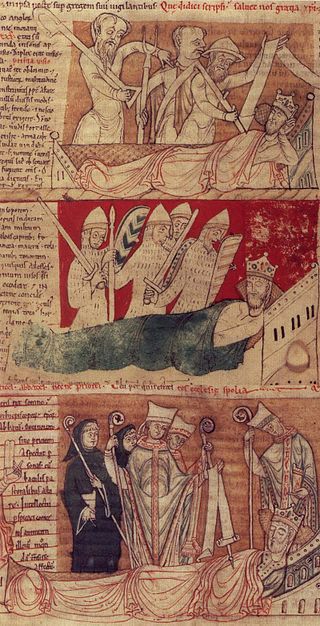

Bede, also known as Saint Bede, the Venerable Bede, and Bede the Venerable, was an English monk and an author and scholar. He was one of the greatest teachers and writers during the Early Middle Ages, and his most famous work, Ecclesiastical History of the English People, gained him the title "The Father of English History". He served at the monastery of St Peter and its companion monastery of St Paul in the Kingdom of Northumbria of the Angles.

Justus was the fourth Archbishop of Canterbury. Pope Gregory the Great sent Justus from Italy to England on a mission to Christianize the Anglo-Saxons from their native paganism, probably arriving with the second group of missionaries despatched in 601. Justus became the first Bishop of Rochester in 604 and attended a church council in Paris in 614.

Old English literature refers to poetry and prose written in Old English in early medieval England, from the 7th century to the decades after the Norman Conquest of 1066, a period often termed Anglo-Saxon England. The 7th-century work Cædmon's Hymn is often considered as the oldest surviving poem in English, as it appears in an 8th-century copy of Bede's text, the Ecclesiastical History of the English People. Poetry written in the mid 12th century represents some of the latest post-Norman examples of Old English. Adherence to the grammatical rules of Old English is largely inconsistent in 12th-century work, and by the 13th century the grammar and syntax of Old English had almost completely deteriorated, giving way to the much larger Middle English corpus of literature.

Aldhelm, Abbot of Malmesbury Abbey, Bishop of Sherborne, and a writer and scholar of Latin poetry, was born before the middle of the 7th century. He is said to have been the son of Kenten, who was of the royal house of Wessex. He was certainly not, as his early biographer Faritius asserts, the brother of King Ine. After his death he was venerated as a saint, his feast day being the day of his death, 25 May.

Cædmon is the earliest English poet whose name is known. A Northumbrian cowherd who cared for the animals at the double monastery of Streonæshalch during the abbacy of St. Hilda, he was originally ignorant of "the art of song" but learned to compose one night in the course of a dream, according to the 8th-century historian Bede. He later became a zealous monk and an accomplished and inspirational Christian poet.

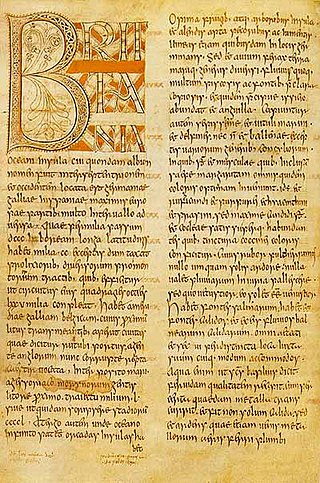

The Ecclesiastical History of the English People, written by Bede in about AD 731, is a history of the Christian Churches in England, and of England generally; its main focus is on the conflict between the pre-Schism Roman Rite and Celtic Christianity. It was composed in Latin, and is believed to have been completed in 731 when Bede was approximately 59 years old. It is considered one of the most important original references on Anglo-Saxon history, and has played a key role in the development of an English national identity.

Ecgbert was an 8th-century cleric who established the archdiocese of York in 735. In 737, Ecgbert's brother became king of Northumbria and the two siblings worked together on ecclesiastical issues. Ecgbert was a correspondent of Bede and Boniface and the author of a legal code for his clergy. Other works have been ascribed to him, although the attribution is doubted by modern scholars.

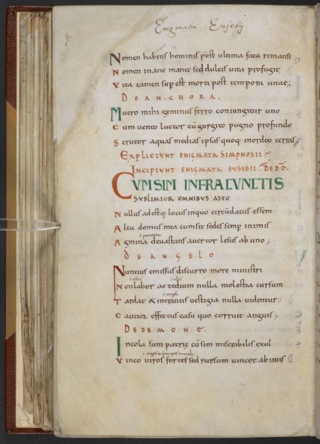

Tatwine was the tenth Archbishop of Canterbury from 731 to 734. Prior to becoming archbishop, he was a monk and abbot of a Benedictine monastery. Besides his ecclesiastical career, Tatwine was a writer, and riddles he composed survive. Another work he composed was on the grammar of the Latin language, which was aimed at advanced students of that language. He was subsequently considered a saint.

Byrhtferth was a priest and monk who lived at Ramsey Abbey in Huntingdonshire in England. He had a deep impact on the intellectual life of later Anglo-Saxon England and wrote many computistic, hagiographic, and historical works. He was a leading man of science and best known as the author of many different works. His Manual (Enchiridion), a scientific textbook, is Byrhtferth's best known work.

Milred was an Anglo-Saxon prelate who served as Bishop of Worcester from c. 744 until his death in 774.

John of Worcester was an English monk and chronicler who worked at Worcester Priory. He is usually held to be the author of the Chronicon ex chronicis.

Eadnoth the Younger or Eadnoth I was a medieval monk and prelate, successively Abbot of Ramsey and Bishop of Dorchester. From a prominent family of priests in the Fens, he was related to Oswald, Bishop of Worcester, Archbishop of York and founder of Ramsey Abbey. Following in the footsteps of his illustrious kinsman, he initially became a monk at Worcester. He is found at Ramsey supervising construction works in the 980s, and around 992 actually became Abbot of Ramsey. As abbot, he founded two daughter houses in what is now Cambridgeshire, namely, a monastery at St Ives and a nunnery at Chatteris. At some point between 1007 and 1009, he became Bishop of Dorchester, a see that encompassed much of the eastern Danelaw. He died at the Battle of Assandun in 1016, fighting Cnut the Great.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons.

Cædmon's Hymn is a short Old English poem attributed to Cædmon, a supposedly illiterate and unmusical cow-herder who was, according to the Northumbrian monk Bede, miraculously empowered to sing in honour of God the Creator. The poem is Cædmon's only known composition.

Frithegod, was a poet and clergyman in the mid 10th-century who served Oda of Canterbury, an Archbishop of Canterbury. As a non-native of England, he came to Canterbury and entered Oda's service as a teacher and scholar. After Oda's death he likely returned to the continent. His most influential writing was a poem on the life of Wilfrid, an 8th-century bishop and saint, named Breviloquium Vitae Wilfridi. Several manuscripts of this poem survive, as well as a few other of Frithegod's poems. He was also known for the complexity of his writings, with one historian even calling them "damnably difficult".

Michael Lapidge, FBA is a scholar in the field of Medieval Latin literature, particularly that composed in Anglo-Saxon England during the period 600–1100 AD; he is an emeritus Fellow of Clare College, Cambridge, a Fellow of the British Academy, and winner of the 2009 Sir Israel Gollancz Prize.

Anglo-Saxon riddles are a significant genre of Anglo-Saxon literature. The riddle was a major, prestigious literary form in early medieval England, and riddles were written both in Latin and Old English verse. The pre-eminent composer of Latin riddles in early medieval England was Aldhelm, while the Old English verse riddles found in the tenth-century Exeter Book include some of the most famous Old English poems.

The Epistola ad Acircium, sive Liber de septenario, et de metris, aenigmatibus ac pedum regulis is a Latin treatise by the West-Saxon scholar Aldhelm. It is dedicated to one Acircius, understood to be King Aldfrith of Northumbria. It was a seminal text in the development of riddles as a literary form in medieval England.

The Enigmata Eusebii are a collection of sixty Latin, hexametrical riddles composed in early medieval England, probably in the eighth century.

References

- 1 2 Joseph P. McGowan, review of Michael Lapidge, ed. and tr. Bede's Latin Poetry. Oxford Medieval Texts. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2019. Pp. xvi, 605. $135.00. ISBN 978-0-19-924277-1, in The Medieval Review (4 April 2021).

- ↑ Patrick Sims-Williams, 'Milred of Worcester's Collection of Latin Epigrams and its Continental Counterparts', Anglo-Saxon England, 10 (1981), 21-38.

- ↑ Patrick, Sims-Williams, Religion and Literature in Western England 600-800, Cambridge Studies in Anglo-Saxon England, 3 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), pp. 328-59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bede's Latin Poetry, ed. and trans. by Michael Lapidge (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 2019), ISBN 9780199242771.

- 1 2 3 Frederick Tupper, Jr., 'Riddles of the Bede Tradition', Modern Philology, 2 (1905), 561-72.

- ↑ Andy Orchard, A Commentary on the Old English and Anglo-Latin Riddle Tradition, Supplements to the Dumbarton Oaks Medieval Library (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2021), pp. 113-15.