Lillian Baker was a conservative author and lecturer. [1] She is known for supporting Japanese-American Internment throughout her career. [2]

Lillian Baker was a conservative author and lecturer. [1] She is known for supporting Japanese-American Internment throughout her career. [2]

Baker was the widow of a World War II veteran. [1] In the 1970s, Baker and others in California objected to the words "concentration camp" on a proposed state historical marker at the site of Manzanar. [2] She opposed efforts to designate Manzanar a national historic site. [1]

Baker downplayed the suffering of Japanese-American internees during the war. [1] She justified Japanese-American Internment, and opposed the government to formally apologize to interned Japanese Americans, and pay reparations to Japanese-American internees. During testimony in front of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), Baker assaulted Nisei veteran James Kawaminami, attempting to snatch the papers from his hands. [3] She wrote several books on the topic of Japanese-American internment. [2]

Lillian Baker was a founder of the Americans for Historical Accuracy. [1] She also founded the International Club for the Collection of Hatpins and Hatpin Holders. In 1976, she was regional campaign manager for S.I. Hayakawa's U.S. Senate bid in California. [2] Baker was awarded by the conservative Freedoms Foundation at Valley Forge. [1]

Baker died on October 21, 1996, at the age of 75 at her home in Gardena. [1]

Manzanar is the site of one of ten American concentration camps, where more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated during World War II from March 1942 to November 1945. Although it had over 10,000 inmates at its peak, it was one of the smaller internment camps. It is located at the foot of the Sierra Nevada mountains in California's Owens Valley, between the towns of Lone Pine to the south and Independence to the north, approximately 230 miles (370 km) north of Los Angeles. Manzanar means "apple orchard" in Spanish. The Manzanar National Historic Site, which preserves and interprets the legacy of Japanese American incarceration in the United States, was identified by the United States National Park Service as the best-preserved of the ten former camp sites.

During World War II, the United States, by order of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, forcibly relocated and incarcerated at least 125,284 people of Japanese descent in 75 identified incarceration sites. Most lived on the Pacific Coast, in concentration camps in the western interior of the country. Approximately two-thirds of the inmates were United States citizens. These actions were initiated by Executive Order 9066 following Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor. Of the 127,000 Japanese Americans who were living in the continental United States at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, 112,000 resided on the West Coast. About 80,000 were Nisei and Sansei. The rest were Issei immigrants born in Japan who were ineligible for U.S. citizenship under U.S. law.

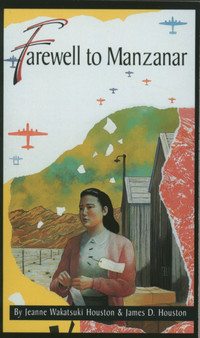

Farewell to Manzanar is a memoir published in 1973 by Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston and James D. Houston. The book describes the experiences of Jeanne Wakatsuki and her family before, during, and following their relocation to the Manzanar internment camp due to the United States government's internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It was adapted into a made-for-TV movie in 1976 starring Yuki Shimoda, Nobu McCarthy, James Saito, Pat Morita, and Mako.

The Heart Mountain War Relocation Center, named after nearby Heart Mountain and located midway between the northwest Wyoming towns of Cody and Powell, was one of ten concentration camps used for the internment of Japanese Americans evicted during World War II from their local communities in the West Coast Exclusion Zone by the executive order of President Franklin Roosevelt.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 is a United States federal law that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been wrongly interned by the United States government during World War II and to "discourage the occurrence of similar injustices and violations of civil liberties in the future". The act was sponsored by California Democratic congressman and former internee Norman Mineta in the House and Hawaii Democrat Senator Spark Matsunaga in the Senate. The bill was supported by the majority of Democrats in Congress, while the majority of Republicans voted against it. The act was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

The Tule Lake National Monument in Modoc and Siskiyou counties in California, consists primarily of the site of the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, one of ten concentration camps constructed in 1942 by the United States government to incarcerate Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes on the West Coast. They totaled nearly 120,000 people, more than two-thirds of whom were United States citizens. Among the inmates, the notation "鶴嶺湖" was sometimes applied.

Minidoka National Historic Site is a National Historic Site in the western United States. It commemorates the more than 13,000 Japanese Americans who were imprisoned at the Minidoka War Relocation Center during the Second World War. Among the inmates, the notation 峰土香 or 峯土香 was sometimes applied.

The Topaz War Relocation Center, also known as the Central Utah Relocation Center (Topaz) and briefly as the Abraham Relocation Center, was an American concentration camp that housed Americans of Japanese descent and immigrants who had come to the United States from Japan, called Nikkei. President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 in February 1942, ordering people of Japanese ancestry to be incarcerated in what were euphemistically called "relocation centers" like Topaz during World War II. Most of the people incarcerated at Topaz came from the Tanforan Assembly Center and previously lived in the San Francisco Bay Area. The camp was opened in September 1942 and closed in October 1945.

The Poston Internment Camp, located in Yuma County in southwestern Arizona, was the largest of the 10 American concentration camps operated by the War Relocation Authority during World War II.

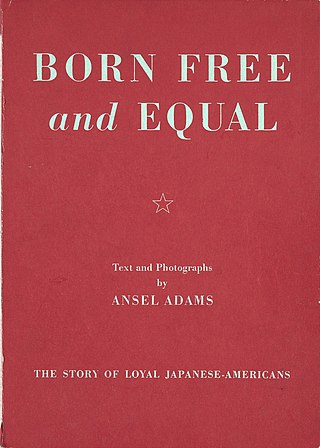

Born Free and Equal: The Story of Loyal Japanese-Americans is a book by Ansel Adams containing photographs from his 1943–1944 visit to the internment camp then named Manzanar War Relocation Center in Owens Valley, Inyo County, California. The book was published in 1944 by U.S. Camera in New York.

On February 19, 1942, shortly after Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the forced removal of over 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast and into internment camps for the duration of the war. The personal rights, liberties, and freedoms of Japanese Americans were suspended by the United States government. In the "relocation centers", internees were housed in tar-papered army-style barracks. Some individuals who protested their treatment were sent to a special camp at Tule Lake, California.

Camp Tulelake was a federal work facility and War Relocation Authority isolation center located in Siskiyou County, five miles west of Tulelake, California. It was established by the United States government in 1935 during the Great Depression for vocational training and work relief for young men, in a program known as the Civilian Conservation Corps. The camp was established initially for CCC enrollees to work on the Klamath Reclamation Project.

William Minoru Hohri was an American political activist and the lead plaintiff in the National Council for Japanese American Redress lawsuit seeking monetary reparations for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. He was sent to the Manzanar concentration camp with his family after the attack on Pearl Harbor triggered the United States' entry into the war. After leading the NCJAR's class action suit against the federal government, which was dismissed, Hohri's advocacy helped convince Congress to pass legislation that provided compensation to each surviving internee. The legislation, signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1988, included an apology to those sent to the camps.

The Manzanar Children's Village was an orphanage for children of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II as a result of Executive Order 9066, under which President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast of the United States. Contained within the Manzanar concentration camp in Owens Valley, California, it held a total of 101 orphans from June 1942 to September 1945.

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga was a Japanese American political activist who played a major role in the Japanese American redress movement. She was the lead researcher of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC), a bipartisan federal committee appointed by Congress in 1980 to review the causes and effects of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II. As a young woman, Herzig-Yoshinaga was confined in the Manzanar Concentration Camp in California, the Jerome War Relocation Center in Arkansas, and the Rohwer War Relocation Center, which is also in Arkansas. She later uncovered government documents that debunked the wartime administration's claims of "military necessity" and helped compile the CWRIC's final report, Personal Justice Denied, which led to the issuance of a formal apology and reparations for former camp inmates. She also contributed pivotal evidence and testimony to the Hirabayashi, Korematsu and Yasui coram nobis cases.

Ralph Lazo was the only known non-spouse, non-Japanese American who voluntarily relocated to a Japanese American internment camp during World War II. His experience was the subject of the 2004 narrative short film Stand Up for Justice: The Ralph Lazo Story.

Mary Kageyama Nomura is an American singer of Japanese descent who was relocated and incarcerated for her ancestry at the Manzanar concentration camp during World War II and became known as The songbird of Manzanar.

Dalton Wells Isolation Center was a camp located in Moab, Utah. The Dalton Wells camp was in use from 1935 to 1943. The camp played a role in two significant events during the twentieth century. During the New Deal programs under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the camp was built as a CCC camp to provide jobs for young men. Starting in 1942 after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the beginning of World War II, the camp was used as a relocation and isolation center for Japanese Americans. The camp never housed large numbers of Japanese Americans since the camp's function was only to house internees deemed "troublemakers" from other relocation camps after problematic events such as the Manzanar riot.