Related Research Articles

Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. This order authorized the secretary of war to prescribe certain areas as military zones, clearing the way for the incarceration of nearly all 120,000 Japanese Americans during the war. Two-thirds of them were U.S. citizens, born and raised in the United States.

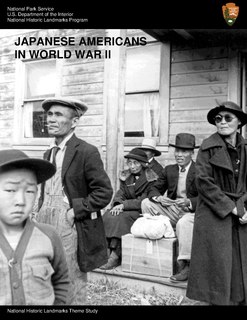

In the United States during World War II, about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, most of whom lived on the Pacific Coast, were forcibly relocated and incarcerated in concentration camps in the western interior of the country. Approximately two-thirds of the internees were United States citizens. These actions were ordered by President Franklin D. Roosevelt shortly after Imperial Japan's attack on Pearl Harbor.

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U.S. 214 (1944), was a landmark decision by the United States Supreme Court to uphold the exclusion of Japanese Americans from the West Coast Military Area during World War II. The decision has widely been criticized, with some scholars describing it as "an odious and discredited artifact of popular bigotry" and as "a stain on American jurisprudence". Chief Justice John Roberts explicitly repudiated the Korematsu decision in his majority opinion in the 2018 case of Trump v. Hawaii. The case is often cited as one of the worst Supreme Court decisions of all time.

Ex parte Endo, or Ex parte Mitsuye Endo, 323 U.S. 283 (1944), was a United States Supreme Court ex parte decision handed down on December 18, 1944, in which the Justices unanimously ruled that the U.S. government could not continue to detain a citizen who was "concededly loyal" to the United States. Although the Court did not touch on the constitutionality of the exclusion of people of Japanese ancestry from the West Coast, which it had found not to violate citizen rights in its Korematsu v. United States decision on the same date, the Endo ruling nonetheless led to the reopening of the West Coast to Japanese Americans after their incarceration in camps across the U.S. interior during World War II.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was the only refugee camp set up in the United States for refugees from Europe. The agency was created by Executive Order 9102 on March 18, 1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was terminated June 26, 1946, by order of President Harry S. Truman.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 is a United States federal law that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been interned by the United States government during World War II. The act was sponsored by California's Democratic Congressman Norman Mineta, an internee as a child, and Wyoming's Republican Senator Alan K. Simpson, who had met Mineta while visiting an internment camp. The third co-sponsor was California Senator Pete Wilson. The bill was supported by the majority of Democrats in Congress, while the majority of Republicans voted against it. The act was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

The Japanese American Citizens League is an Asian American civil rights charity, headquartered in San Francisco, with regional offices across the United States.

The Tule Lake National Monument in Modoc and Siskiyou counties in California, consists primarily of the site of the Tule Lake War Relocation Center, one of ten concentration camps constructed in 1942 by the United States government to incarcerate Japanese Americans forcibly removed from their homes on the West Coast. They totaled nearly 120,000 people, more than two-thirds of whom were United States citizens.

On February 19, 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 relocating over 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast into internment camps for the duration of the war. The personal rights, liberties, and freedoms of Japanese Americans were suspended by the United States government.

The following article focuses on the movement to obtain redress for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, and significant court cases that have shaped civil and human rights for Japanese Americans and other minorities. These cases have been the cause and/or catalyst to many changes in United States law. But mainly, they have resulted in adjusting the perception of Asian immigrants in the eyes of the American government.

Violet Kazue de Cristoforo was a Japanese American poet, composer and translator of haiku. Her haiku reflected the time that she and her family spent in detention in Japanese internment camps during World War II. She wrote more than a dozen books of poetry during her lifetime. Her best known works are Poetic Reflections of the Tule Lake Internment Camp, 1944, which was written nearly 50 years after her detention and May Sky: There Is Always Tomorrow; An Anthology of Japanese American Concentration Camp Kaiko Haiku, for which she was the editor.

Karl Robin Bendetsen was an American colonel who served in Washington Army National Guard during World War II and later as the Under Secretary of the Army. Bendetsen is remembered primarily for his role as an architect of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

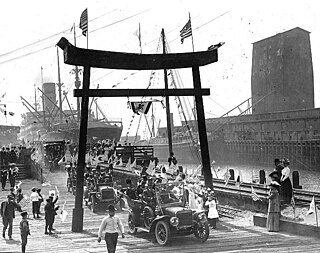

Japanese American history is the history of Japanese Americans or the history of ethnic Japanese in the United States. People from Japan began immigrating to the U.S. in significant numbers following the political, cultural, and social changes stemming from the 1868 Meiji Restoration. Large-scale Japanese immigration started with immigration to Hawaii during the first year of the Meiji period in 1868.

Densho is a nonprofit organization based in Seattle, Washington whose mission is “to preserve and share history of the WWII incarceration of Japanese Americans to promote equity and justice today.” Densho collects video oral histories, photos, documents, and other primary source materials regarding Japanese American history, with a focus on the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. Densho offers a free digital archive of these primary sources, in addition to an online encyclopedia and curricula, for educational purposes.

William Minoru Hohri was an American political activist and the lead plaintiff in the National Council for Japanese American Redress lawsuit seeking monetary reparations for the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. He was sent to the Manzanar concentration camp with his family after the attack on Pearl Harbor triggered the United States' entry into the war. After leading the NCJAR's class action suit against the federal government, which was dismissed, Hohri's advocacy helped convince Congress to pass legislation that provided compensation to each surviving internee. The legislation, signed by President Ronald Reagan in 1988, included an apology to those sent to the camps.

Mitsuye Maureen Endo Tsutsumi was an American woman of Japanese descent who was placed in an internment camp during World War II. Endo filed a writ of habeas corpus that ultimately led to a United States Supreme Court ruling that the U.S. government could not continue to detain a citizen who was "concededly loyal" to the United States.

Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga was an American political activist who played a major role in the Japanese American redress movement. She was the lead researcher of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians, a bipartisan federal committee appointed by Congress in 1980 to review the causes and effects of the Japanese American incarceration during World War II. Herzig-Yoshinaga, who was confined in the Manzanar, California and Jerome and Rohwer, Arkansas concentration camps as a young woman, uncovered government documents that debunked the wartime administration's claims of "military necessity" and helped compile the CWRIC's final report, Personal Justice Denied, which led to the issuance of a formal apology and reparations for former camp inmates. She also contributed pivotal evidence and testimony to the Hirabayashi, Korematsu and Yasui coram nobis cases.

There is a population of Japanese Americans and Japanese expatriates in Greater Seattle, whose origins date back to the second half of the 19th century. Prior to World War II, Seattle's Japanese community had grown to become the second largest Nihonmachi on the West Coast of North America.

Lillian Baker was a conservative author and lecturer She is known for supporting Japanese-American Internment throughout her career.

William M. Marutani was the first Asian-American male judge in Pennsylvania (1975). Marutani was the only Japanese American commissioner to sit on the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC).

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Personal Justice Denied: Report of the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians". National Archives. Government Printing Office, Washington DC. December 1982. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ↑ "Redress Hearings Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) Hearings (1981)". Nikkei for Civil Rights and Redress. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ "Internment History Timeline". Children of the Camps. PBS.

- ↑ "Public Law 100-383 -- August 10, 1988". Internment Archives. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ "Text of the Civil Liberties Act of 1987". GovTrack. GovTrack. Retrieved 21 June 2014.

- ↑ "Japanese Latin Americans | Densho Encyclopedia". encyclopedia.densho.org. Retrieved 2021-09-23.