This is a list of inmates of Manzanar , an American concentration camp in California used during World War II to hold people of Japanese descent.

- Koji Ariyoshi (1914–1976), a Nisei labor activist

- Paul Bannai (1920–2019), an American politician

- Frank Chuman (1917–2022), a civil rights attorney and author who wrote the Japanese American legal history "Bamboo People" and memoir "Manzanar and Beyond".

- Sue Kunitomi Embrey (1923–2006) was an editor of the Manzanar Free Press, the camp newspaper, and wove camouflage nets to support the war effort. She left Manzanar in late 1943 for Madison, Wisconsin and one year later moved to Chicago, Illinois. Returning to California in 1948, she went on to become a schoolteacher and a labor and community activist. [1] In 1969, Embrey was one of approximately 150 people who attended the first organized Manzanar Pilgrimage (see Manzanar Pilgrimage section, below) and was one of the founders of the annual event. She also went on to become the primary force behind the preservation of the site and its gaining National Historic Site status until her death in May 2006. [1] [2]

- Jerry Fujikawa (1912–1983), an American stage, screen and television actor

- Henry Fukuhara (1913–2010), who was born in Fruitland, California, was incarcerated with his family in April 1942. [3] An artist and watercolorist, Fukuhara would later teach a series of annual artistic workshops at Manzanar beginning in 1998. [3] His workshops, which usually had about 80 students a year, including Milford Zornes, used outdoor structures at Manzanar to teach water color painting. [3]

- Fumiko Hayashida (1911–2014), an American activist,

- Aiko Herzig-Yoshinaga (1945–2018) was born in Los Angeles, was 17 years old when she was incarcerated at Manzanar. Later, she was incarcerated at Jerome and Rohwer, Arkansas. [4] Yoshinaga-Herzig later moved to New York, where she became a community activist in the 1960s and was a member of Asian Americans for Action (AAA), the first Asian American political organization on the East Coast. It included Asian American activists Bill and Yuri Kochiyama. [4] Although she was not trained to be an archival researcher, Yoshinaga-Herzig decided to find out what historical documents about her and her family might exist at the National Archives. [4]

- Herzig-Yoshinaga and her husband, John "Jack" Herzig, pored over mountains of documents from the War Relocation Authority, a task that "was roughly equivalent to indexing all the information in a library, working from a card catalog that only gave a subject description by shelf, without giving individual book titles or authors." [4] Their efforts resulted in the discovery of evidence that the US Government perjured itself before the United States Supreme Court in the 1944 cases Korematsu v. United States , Hirabayashi v. United States, and Yasui v. United States which challenged the constitutionality of the relocation and incarceration. The government had presented falsified evidence to the Court, destroyed evidence, and had withheld other vital information. [5] This evidence provided the legal basis Japanese Americans needed to seek redress and reparations for their wartime imprisonment. The Herzigs' research was also valuable in their work with the National Coalition for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), which filed a class-action lawsuit against the US Government on behalf of the incarcerated people. The US Supreme Court ruled against the plaintiff. [4]

- William Hohri (1927–2010), [6] was incarcerated at Manzanar when he was 15 years old. His family entered Manzanar on April 3, 1942, and remained behind the barbed wire until August 25, 1945. [7] Hohri became a civil rights and anti-war activist after World War II. In the late 1970s he became the chair of the National Coalition for Japanese American Redress (NCJAR), which brought a class action lawsuit against the US Government on March 16, 1983, asserting that it had unjustly incarcerated Japanese Americans during World War II. [8] The lawsuit stated 22 causes of action, including fifteen alleged violations of constitutional rights, and sought $27 billion in damages. [9] Despite the fact the US Supreme Court eventually ruled against the class action plaintiffs, the lawsuit helped bring the Japanese American case for redress and reparations to public awareness. It showed the Congress and the Executive Branch that the US Government would have far greater exposure in the still-pending lawsuit than by legislation under consideration in Congress for reparations. The proposed bill called for $20,000 reparations payments to each former inmate or their immediate relatives, along with money for a civil liberties education fund (see Civil Liberties Act of 1988). [10] [11] [6]

...(The class action lawsuit) remained active until after Congress had passed the redress legislation. While it remained alive, it played a significant part in publicizing the issues. The NCJAR lawsuit demanded $220,000 for each individual whose liberties had been denied. This was more than 10 times greater than the $20,000 per surviving incarcerated person that the redress bills proposed, allowing proponents to portray the legislative solution as a moderate alternative. [4]

- Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston (1934–2024), a writer

- Michi Itami (born 1938), a visual artist

- Isao Kikuchi (1921–2017), an American graphic designer, painter, carver and illustrator

- Joseph Kurihara (1895–1965), a renunciant, also interned at Tule Lake

- Ralph Lazo (1924–1992), from Los Angeles, was of Mexican American and Irish American descent, but when at age 16 he learned that his Japanese American friends and neighbors were being forcibly removed and incarcerated at Manzanar, he was outraged. [12] Lazo was so incensed that he joined friends on a train that took hundreds to Manzanar in May 1942. [13] Manzanar officials never asked him about his ancestry. [14] "Internment was immoral," Lazo told the Los Angeles Times . "It was wrong, and I couldn't accept it." [12] "These people hadn't done anything that I hadn't done except to go to Japanese language school." [15] In 1944, Lazo was elected president of his class at Manzanar High School. [12] He remained at Manzanar until August of that year, when he was inducted into the US Army. [12] He served as a staff sergeant in the South Pacific until 1946, helping liberate the Philippines. Lazo was awarded the Bronze Star for heroism in combat. [12] After the war, he was a strong supporter of redress and reparations for Japanese Americans incarcerated during the war. [15] The film Stand Up for Justice: The Ralph Lazo Story documents his life story, particularly his stand against the incarceration. [16]

- George H. Minamiki, S.J. (1919–2002), a theologian and educator

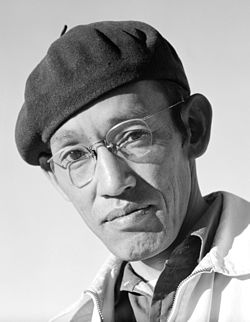

- Toyo Miyatake (1895–1979), who was born in Kagawa, Shikoku, Japan, immigrated to the United States in 1909. He settled in the Little Tokyo section of Los Angeles, and was incarcerated at Manzanar along with his family. A photographer, Miyatake smuggled a lens and film holder into Manzanar and later had a craftsman construct a wooden box with a door that hid the lens. He took many now-famous photos of life and the conditions at Manzanar. His contraband camera was eventually discovered by the camp administration and confiscated. However, camp director Ralph Merritt later allowed Miyatake to photograph freely within the camp, even though he was not allowed to actually press the shutter button, requiring a guard or camp official to perform this simple task. Merritt finally saw no point to this technicality, and allowed Miyatake to take photos. [17]

- Chiye Mori (1915–2001), a poet and journalist

- Rollin Moriyama (1907–1992), a Japanese character actor

- Grace Aiko Nakamura (1927–2017), a teacher

- Robert A. Nakamura (born 1936), a filmmaker and teacher

- Hayward Nishioka (born 1942), a physical education instructor and former judo competitor

- Mary Nomura (born 1925), a singer

- Albert Nozaki (1912–2003), an art director

- Dennis M. Ogawa (born 1943), professor and former chair at the University of Hawaii at Manoa

- Frank Okamura (1911–2006), a horticulturalist

- Joyce Nakamura Okazaki, (born 1934), an official with the Manzanar Committee

- Tura Satana (1938–2011), an actress

- Gordon H. Sato (1927–2017), an American cell biologist

- Gary Shimokawa (born 1942), an American director and producer

- Tak Shindo (1922–2002), a musician, composer and arranger

- Larry Shinoda (1930–1997), a noted American automotive designer

- Paul Takagi (1923-2015), criminologist, civil rights activist. [18]

- Iwao Takamoto (1925–2007), an American animator, television producer, and film director

- Martin Tanaka (1921–1991), an American professional wrestler

- Togo Tanaka (1916–2009), editor of the Rafu Shimpo newspaper, was sent to the Manzanar, where he used his journalism experience to document conditions in the camp. A supporter of cooperation with the authorities, he was labeled a collaborator and was transferred to Death Valley after being the target of riots before the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor. [19]

- John Tateishi (born 1939), former Redress Director of the Japanese American Citizens League

- Kazue Togasaki (1897–1992), one of the first two women of Japanese ancestry to earn a medical degree in the United States. Also interned at Topaz and Tule Lake.

- Harry Ueno (1907–2004), was a Kibei (native-born Japanese American educated in Japan) who was incarcerated at Manzanar with his wife and children. [20] After volunteering for mess hall work, Ueno discovered that Manzanar camp staff were stealing rationed sugar and meat and selling them on the black market. [20] [21] This led to his arrest, which resulted in Ueno becoming the focal point of the Manzanar Riot. [20] Ueno was one of the inmates featured in Emiko Omori's Emmy Award-winning film Rabbit in the Moon. [22]

- Takuji Yamashita (1874–1959), an early 20th-century civil rights pioneer. Also interned at Tule Lake and Minidoka.

- Dave Yanai (born 1943), a basketball coach.

- Karl Yoneda (1906–1999) was born in Glendale, California, but his family moved back to Japan in 1913. [23] [24] He became an activist early in his life. [23] With Japan on a path towards war, Yoneda returned to the United States rather than be drafted into the Japanese Army. [23] He arrived in San Francisco on December 14, 1926. He was taken to the Immigration Detention House on Angel Island, where he was detained for two months, despite having his California birth certificate. [24] Yoneda later moved to Los Angeles, where he found work organizing with the Trade Union Educational League, and later the Japanese Workers' Association. [23] Yoneda arrived at Manzanar on March 22, 1942, one of the first Japanese Americans to arrive as a volunteer to build the camp. [25] Yoneda later distinguished himself in service to the US, volunteering to serve in the Military Intelligence Service. [26] After the war, Yoneda continued to support progressive causes and civil and human rights issues. [23]

- Wendy Yoshimura (born 1943), an American still life watercolor painter and activist