Executive Order 9066 was a United States presidential executive order signed and issued during World War II by United States president Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942. "This order authorized the forced removal of all persons deemed a threat to national security from the West Coast to "relocation centers" further inland—resulting in the incarceration of Japanese Americans." Two-thirds of the 125,000 people displaced were U.S. citizens.

During World War II, the United States forcibly relocated and incarcerated about 120,000 people of Japanese descent in ten concentration camps operated by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), mostly in the western interior of the country. About two-thirds were U.S. citizens. These actions were initiated by Executive Order 9066, issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on February 19, 1942, following the outbreak of war with the Empire of Japan in December 1941. About 127,000 Japanese Americans then lived in the continental U.S., of which about 112,000 lived on the West Coast. About 80,000 were Nisei and Sansei. The rest were Issei immigrants born in Japan, who were ineligible for citizenship. In Hawaii, where more than 150,000 Japanese Americans comprised more than one-third of the territory's population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were incarcerated.

Milton Stover Eisenhower was an American academic administrator. He served as president of three major American universities: Kansas State University, Pennsylvania State University, and Johns Hopkins University. Eisenhower was also the head of the U.S. delegation to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO). He was the youngest brother of, and advisor to, U.S. President Dwight D. Eisenhower.

The War Relocation Authority (WRA) was a United States government agency established to handle the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. It also operated the Fort Ontario Emergency Refugee Shelter in Oswego, New York, which was the only refugee camp set up in the United States for refugees from Europe. The agency was created by Executive Order 9102 on March 18, 1942, by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and was terminated June 26, 1946, by order of President Harry S. Truman.

The Civil Liberties Act of 1988 is a United States federal law that granted reparations to Japanese Americans who had been wrongly interned by the United States government during World War II and to "discourage the occurrence of similar injustices and violations of civil liberties in the future". The act was sponsored by California Democratic congressman and former internee Norman Mineta in the House and Hawaii Democratic Senator Spark Matsunaga in the Senate. The bill was supported by the majority of Democrats in Congress, while the majority of Republicans voted against it. The act was signed into law by President Ronald Reagan.

The Gila River War Relocation Center was an American concentration camp in Arizona, one of several built by the War Relocation Authority (WRA) during the Second World War for the incarceration of Japanese Americans from the West Coast. It was located within the Gila River Indian Reservation near the town of Sacaton, about 30 mi (48.3 km) southeast of Phoenix. With a peak population of 13,348, it became the fourth-largest city in the state, operating from May 1942 to November 16, 1945.

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U.S. 81 (1943), was a case in which the United States Supreme Court held that the application of curfews against members of a minority group were constitutional when the nation was at war with the country from which that group's ancestors originated. The case arose out of the issuance of Executive Order 9066 following the attack on Pearl Harbor and the U.S. entry into World War II. President Franklin D. Roosevelt had authorized military commanders to secure areas from which "any or all persons may be excluded", and Japanese Americans living in the West Coast were subject to a curfew and other restrictions before being removed to internment camps. The plaintiff, Gordon Hirabayashi, was convicted of violating the curfew and had appealed to the Supreme Court. Yasui v. United States was a companion case decided the same day. Both convictions were overturned in coram nobis proceedings in the 1980s.

John Lesesne DeWitt was a four-star general in the United States Army. He was best known for overseeing the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) was a group of nine people appointed by the U.S. Congress in 1980 to conduct an official governmental study into the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

The Japanese-American Claims Act is a law passed by the United States Congress and signed by President Harry S. Truman on July 2, 1948. The law authorized the settlement of property loss claims by people of Japanese descent who were removed from the Pacific Coast area during World War II. According to a Senate report on the Act, there were concerns about whether the United States government had the right to evacuate and place all people of Japanese ancestry in internment camps. As result of being placed in the Japanese internment camps there was great loss of property, belongings, business, "and the principles of justice and responsible government require that there should be compensation for such losses. "Congress over time appropriated $38 million to settle 23,000 claims for damages totaling $131 million. The final claim was adjudicated in 1965."

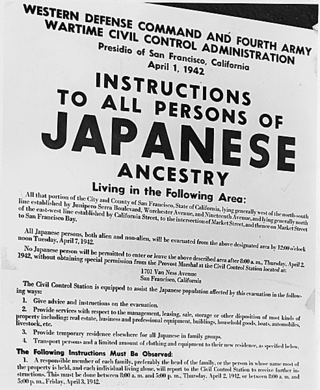

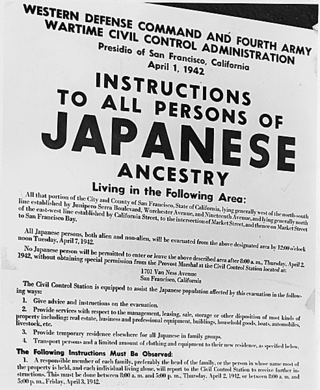

On February 19, 1942, shortly after Japan's surprise attack on Pearl Harbor in Hawaii, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 authorizing the forced removal of over 110,000 Japanese Americans from the West Coast and into internment camps for the duration of the war. The personal rights, liberties, and freedoms of Japanese Americans were suspended by the United States government. In the "relocation centers", internees were housed in tar-papered army-style barracks. Some individuals who protested their treatment were sent to a special camp at Tule Lake, California.

Karl Robin Bendetsen was an American politician and military officer who served in the Washington Army National Guard during World War II and later as the United States Under Secretary of the Army. Bendetsen is remembered primarily for his role as an architect of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, a role he tried to downplay in later years.

Togo "Walter" Tanaka was an American newspaper journalist and editor who reported on the difficult conditions in the Manzanar camp, where he was one of 110,000 Japanese Americans who had been relocated after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

The Manzanar Children's Village was an orphanage for children of Japanese ancestry incarcerated during World War II as a result of Executive Order 9066, under which President Franklin D. Roosevelt authorized the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast of the United States. Contained within the Manzanar concentration camp in Owens Valley, California, it held a total of 101 orphans from June 1942 to September 1945.

Mitsuye Endo Tsutsumi was an American woman of Japanese descent who was unjustly incarcerated during World War II in concentration camps sponsored by the War Relocation Authority. Endo filed a writ of habeas corpus that ultimately led to a United States Supreme Court ruling that the U.S. government could not continue to detain a citizen who was "concededly loyal" to the United States.

Dillon Seymour Myer was a United States government official who served as Director of the War Relocation Authority during World War II, Director of the Federal Public Housing Authority, and Commissioner of the Bureau of Indian Affairs in the early 1950s. He also served as President of the Institute of Inter-American Affairs.

The Japanese American Evacuation and Resettlement Study (JERS) was a research project funded by the War Relocation Authority (WRA), an agency responsible for overseeing the relocation of Japanese Americans, The University of California, the Giannini Foundation, the Columbian Foundation, and the Rockefeller Foundation with the total amount of funding reaching almost 100,000 U.S. dollars. It was conducted by a team of social scientists at the University of California, Berkeley. The team was led by sociologist Dorothy Swaine Thomas, a Lecturer in Sociology for the Giannini Foundation and a professor of rural sociology, and included anthropologists John Collier Jr. and Alexander Leighton, among others. The study combined each of the major social sciences such as sociology, social anthropology, political science, social psychology, and economics to effectively illustrate the effects of internment on Japanese Americans. The terminology of "relocation" can be confusing: The WRA termed the forced removal of Japanese Americans from the West Coast an "evacuation" and called the incarceration of these people in the ten camps as "relocation." Later it also applied the term "relocation" to the program that enabled the evacuees to leave the camps (provided they had been certified as loyal.

The Temporary Detention Camp for Japanese Americans / Santa Anita Assembly Center is one of the places Japanese Americans were held during World War II. The Santa Anita Assembly Center was designated a California Historic Landmark (No.934.07) on May 13, 1980. The Santa Anita Assembly Center is located in what is now the Santa Anita Racetrack in Arcadia, California in Los Angeles County.

Cherry Kinoshita was a Japanese American activist and leader in the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL). She helped found the Seattle Evacuation Redress Committee and fought for financial compensation for Japanese Americans who had been incarcerated during World War II.

Dalton Wells Isolation Center was an American internment camp located in Moab, Utah. The Dalton Wells camp was in use from 1935 to 1943. The camp played a role in two significant events during the twentieth century. During the New Deal programs under President Franklin D. Roosevelt, the camp was built as a CCC camp to provide jobs for young men. Starting in 1942 after the attack on Pearl Harbor and the beginning of World War II, the camp was used as a relocation and isolation center for Japanese Americans. The camp never housed large numbers of Japanese Americans since the camp's function was only to house internees deemed "troublemakers" from other relocation camps after problematic events such as the Manzanar riot. Some consider the camp illegal because it was not authorized by Executive Order 9066.