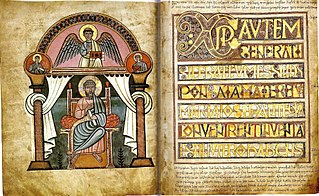

The Lindisfarne Gospels is an illuminated manuscript gospel book probably produced around the years 715–720 in the monastery at Lindisfarne, off the coast of Northumberland, which is now in the British Library in London. The manuscript is one of the finest works in the unique style of Hiberno-Saxon or Insular art, combining Mediterranean, Anglo-Saxon and Celtic elements.

An illuminated manuscript is a formally prepared document where the text is decorated with flourishes such as borders and miniature illustrations. Often used in the Roman Catholic Church for prayers and liturgical books such as psalters and courtly literature, the practice continued into secular texts from the 13th century onward and typically include proclamations, enrolled bills, laws, charters, inventories, and deeds.

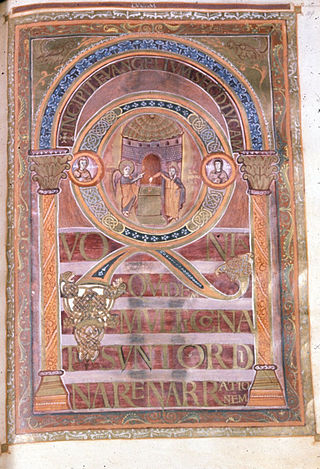

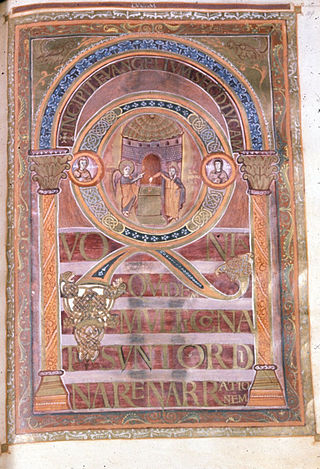

The Book of Kells is an illuminated manuscript and Celtic Gospel book in Latin, containing the four Gospels of the New Testament together with various prefatory texts and tables. It was created in a Columban monastery in either Ireland or Scotland, and may have had contributions from various Columban institutions from each of these areas. It is believed to have been created c. 800 AD. The text of the Gospels is largely drawn from the Vulgate, although it also includes several passages drawn from the earlier versions of the Bible known as the Vetus Latina. It is regarded as a masterwork of Western calligraphy and the pinnacle of Insular illumination. The manuscript takes its name from the Abbey of Kells, County Meath, which was its home for centuries.

The Book of Durrow is an illuminated manuscript dated to c. 700 that consists of text from the four Gospels gospel books, written in an Irish adaption of Vulgate Latin, and illustrated in the Insular script style.

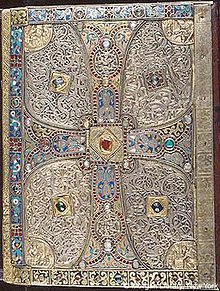

The Codex Aureus of St. Emmeram is a 9th-century illuminated Gospel Book. It takes its name from Saint Emmeram's Abbey, where it was for most of its history and is lavishly illuminated. The cover of the codex is decorated with gems and relief figures in gold, and can be precisely dated to 870, and is an important example of Carolingian art, as well as one of very few surviving treasure bindings of this date.

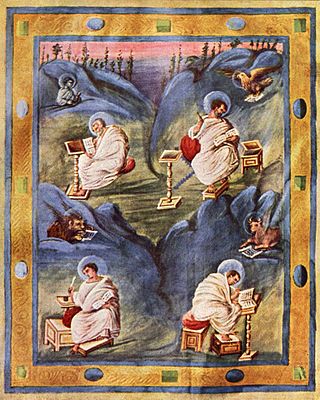

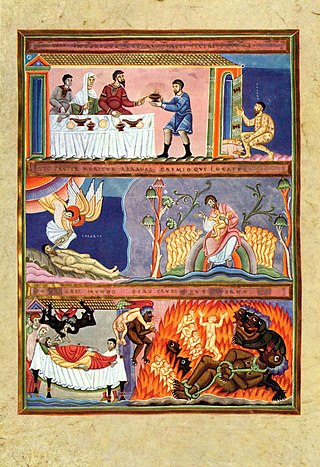

The Irish Gospels of St. Gall or Codex Sangallensis 51 is an 8th-century Insular Gospel Book, written either in Ireland or by Irish monks in the Abbey of St. Gall in Switzerland, where it is now in the Abbey library of St. Gallen as MS 51. It has 134 folios. Amongst its eleven illustrated pages are a Crucifixion, a Last Judgement, a Chi Rho monogram page, a carpet page, and Evangelist portraits.

British Library, Add MS 40618 is a late 8th century illuminated Irish Gospel Book with 10th century Anglo-Saxon additions. The manuscript contains a portion of the Gospel of Matthew, the majority of the Gospel of Mark and the entirety of the Gospels of Luke and John. There are three surviving Evangelist portraits, one original and two 10th century replacements, along with 10th century decorated initials. It is catalogued as number 40618 in the Additional manuscripts collection at the British Library.

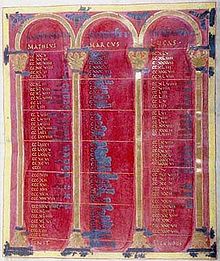

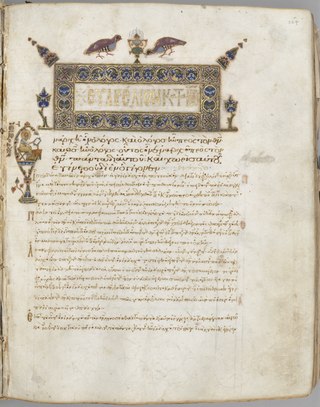

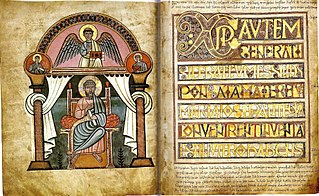

British Library, Add MS 11848 is an illuminated Carolingian Latin Gospel Book produced at Tours. It contains the Vulgate translation of the four Gospels written on vellum in Carolingian minuscule with Square and Rustic Capitals and Uncials as display scripts. The manuscript has 219 extant folios which measure approximately 330 by 230 mm. The text is written in area of about 205 by 127 mm. In addition to the text of the Gospels, the manuscript contains the letter of St. Jerome to Pope Damasus and of Eusebius of Caesarea to Carpian, along with the Eusebian canon tables. There are prologues and capitula lists before each Gospel. A table of readings for the year was added, probably between 1675 and 1749, to the end of the volume. This is followed by a list of capitula incipits and a word grid which were added in the Carolingian period.

The Stockholm Codex Aureus is a Gospel book written in the mid-eighth century in Southumbria, probably in Canterbury, whose decoration combines Insular and Italian elements. Southumbria produced a number of important illuminated manuscripts during the eighth and early ninth centuries, including the Vespasian Psalter, the Stockholm Codex Aureus, three Mercian prayer books, the Tiberius Bede and the British Library's Royal Bible.

Carolingian art comes from the Frankish Empire in the period of roughly 120 years from about 780 to 900—during the reign of Charlemagne and his immediate heirs—popularly known as the Carolingian Renaissance. The art was produced by and for the court circle and a group of important monasteries under Imperial patronage; survivals from outside this charmed circle show a considerable drop in quality of workmanship and sophistication of design. The art was produced in several centres in what are now France, Germany, Austria, northern Italy and the Low Countries, and received considerable influence, via continental mission centres, from the Insular art of the British Isles, as well as a number of Byzantine artists who appear to have been resident in Carolingian centres.

Ottonian art is a style in pre-romanesque German art, covering also some works from the Low Countries, northern Italy and eastern France. It was named by the art historian Hubert Janitschek after the Ottonian dynasty which ruled Germany and Northern Italy between 919 and 1024 under the kings Henry I, Otto I, Otto II, Otto III and Henry II. With Ottonian architecture, it is a key component of the Ottonian Renaissance. However, the style neither began nor ended to neatly coincide with the rule of the dynasty. It emerged some decades into their rule and persisted past the Ottonian emperors into the reigns of the early Salian dynasty, which lacks an artistic "style label" of its own. In the traditional scheme of art history, Ottonian art follows Carolingian art and precedes Romanesque art, though the transitions at both ends of the period are gradual rather than sudden. Like the former and unlike the latter, it was very largely a style restricted to a few of the small cities of the period, and important monasteries, as well as the court circles of the emperor and his leading vassals.

The Otho-Corpus Gospels is a badly damaged and fragmentary 8th century illuminated manuscript. It was part of the Cotton library and was mostly burnt in the 1731 fire at Ashburnham House. The manuscript now survives as charred fragments in the British Library. Thirty six pages of the manuscript were not in the Cotton collection and survived the fire. They are now in the library of Corpus Christi College, Cambridge.

A treasure binding or jewelled bookbinding is a luxurious book cover using metalwork in gold or silver, jewels, or ivory, perhaps in addition to more usual bookbinding material for book covers such as leather, velvet, or other cloth. The actual bookbinding technique is the same as for other medieval books, with the folios, normally of vellum, stitched together and bound to wooden cover boards. The metal furnishings of the treasure binding are then fixed, normally by tacks, onto these boards. Treasure bindings appear to have existed from at least Late Antiquity, though there are no surviving examples from so early, and Early Medieval examples are very rare. They were less used by the end of the Middle Ages, but a few continued to be produced in the West even up to the present day, and many more in areas where Eastern Orthodoxy predominated. The bindings were mainly used on grand illuminated manuscripts, especially gospel books designed for the altar and use in church services, rather than study in the library.

The Vienna Coronation Gospels, also known simply as the Coronation Gospels, is a late 8th century illuminated gospel book produced at the court of Charlemagne in Aachen. It was used by the future emperor at his coronation on Christmas Day 800, when he placed three fingers of his right hand on the first page of the Gospel of Saint John and took his oath. Traditionally, it is considered to be the same manuscript that was found in the tomb of Charlemagne when it was opened in the year 1000 by Emperor Otto III. The Coronation Evangeliar cover was created by Hans von Reutlingen, c. 1500. The Coronation Evangeliar is part of the Imperial Treasury (Schatzkammer) in the Hofburg Palace in Vienna, Austria.

A carpet page is a full page in an illuminated manuscript containing intricate, non-figurative, patterned designs. They are a characteristic feature of Insular manuscripts, and typically placed at the beginning of a Gospel Book. Carpet pages are characterised by mainly geometrical ornamentation which may include repeated animal forms. They are distinct from pages devoted to highly decorated historiated initials, though the style of decoration may be very similar.

Insular art, also known as Hiberno-Saxon art, was produced in the post-Roman era of Great Britain and Ireland. The term derives from insula, the Latin term for "island"; in this period Britain and Ireland shared a largely common style different from that of the rest of Europe. Art historians usually group Insular art as part of the Migration Period art movement as well as Early Medieval Western art, and it is the combination of these two traditions that gives the style its special character.

The Codex Aureus of Echternach is an illuminated Gospel Book, created in the approximate period 1030–1050, with a re-used front cover from around the 980s. It is now in the Germanisches Nationalmuseum in Nuremberg.

The Cross of Lothair or Lothair Cross is a crux gemmata processional cross dating from about 1000 AD, though its base dates from the 14th century. It was made in Germany, probably at Cologne. It is an outstanding example of medieval goldsmith's work, and "an important monument of imperial ideology", forming part of the Aachen Cathedral Treasury, which includes several other masterpieces of sacral Ottonian art. The measurements of the original portion are 50 cm height, 38.5 cm width, 2.3 cm depth.

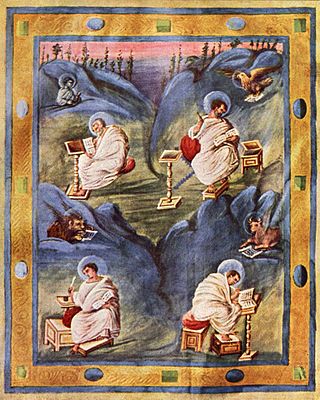

The Harley Golden Gospels, British Library, Harley MS 2788, is a Carolingian illuminated manuscript Gospel book produced in about 800–825, probably in Aachen, Germany. It is one of the manuscripts attributed to the "Ada School", which is named after the Ada Gospels. It has four pairs of full-page Evangelist portraits and illuminated "Incipit" pages, canon tables, and other illuminations. As with other examples of the Codex Aureus, the text is written in gold ink.

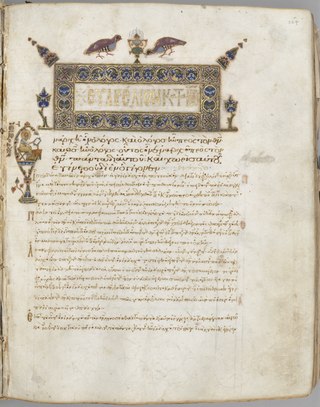

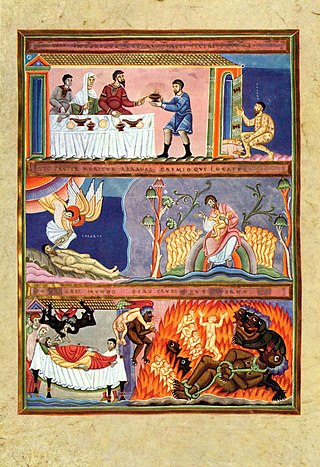

The Gregorian Sacramentary is a 10th-century illuminated Latin manuscript containing a sacramentary. Since the 16th century it has been in the Vatican Library, shelfmark Vat. Lat. 3806.