The First Epistle of John is the first of the Johannine epistles of the New Testament, and the fourth of the catholic epistles. There is no scholarly consensus as to the authorship of the Johannine works. The author of the First Epistle is termed John the Evangelist, who most modern scholars believe is not the same as John the Apostle. Most scholars believe the three Johannine epistles have the same author, but there is no consensus if this was also the author of the Gospel of John.

Luke the Evangelist is one of the Four Evangelists—the four traditionally ascribed authors of the canonical gospels. The Early Church Fathers ascribed to him authorship of both the Gospel of Luke and the Acts of the Apostles. Prominent figures in early Christianity such as Jerome and Eusebius later reaffirmed his authorship, although a lack of conclusive evidence as to the identity of the author of the works has led to discussion in scholarly circles, both secular and religious.

Matthew the Apostle is named in the New Testament as one of the twelve apostles of Jesus. According to Christian traditions, he was also one of the four Evangelists as author of the Gospel of Matthew, and thus is also known as Matthew the Evangelist.

Mary Magdalene was a woman who, according to the four canonical gospels, traveled with Jesus as one of his followers and was a witness to His crucifixion and resurrection. She is mentioned by name twelve times in the canonical gospels, more than most of the apostles and more than any other woman in the gospels, other than Jesus's family. Mary's epithet Magdalene may be a toponymic surname, meaning that she came from the town of Magdala, a fishing town on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee in Roman Judea.

The New Testament (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events relating to first-century Christianity. The New Testament's background, the first division of the Christian Bible, is called the Old Testament, which is based primarily upon the Hebrew Bible; together they are regarded as Sacred Scripture by Christians.

Polycarp was a Christian bishop of Smyrna. According to the Martyrdom of Polycarp, he died a martyr, bound and burned at the stake, then stabbed when the fire failed to consume his body. Polycarp is regarded as a saint and Church Father in the Catholic Church, Eastern Orthodox Church, Oriental Orthodox Churches, Lutheranism, and Anglicanism.

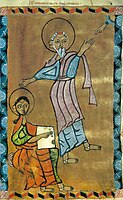

John the Apostle, also known as Saint John the Beloved and, in Eastern Orthodox Christianity, Saint John the Theologian, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus according to the New Testament. Generally listed as the youngest apostle, he was the son of Zebedee and Salome. His brother James was another of the Twelve Apostles. The Church Fathers identify him as John the Evangelist, John of Patmos, John the Elder, and the Beloved Disciple, and testify that he outlived the remaining apostles and was the only one to die of natural causes, although modern scholars are divided on the veracity of these claims.

Mark the Evangelist, also known as John Mark or Saint Mark, is the person who is traditionally ascribed to be the author of the Gospel of Mark. Modern Bible scholars have concluded that the Gospel of Mark was written by an anonymous author rather than an identifiable historical figure. According to Church tradition, Mark founded the episcopal see of Alexandria, which was one of the five most important sees of early Christianity. His feast day is celebrated on April 25, and his symbol is the winged lion.

An epistle is a writing directed or sent to a person or group of people, usually an elegant and formal didactic letter. The epistle genre of letter-writing was common in ancient Egypt as part of the scribal-school writing curriculum. The letters in the New Testament from Apostles to Christians are usually referred to as epistles. Those traditionally attributed to Paul are known as Pauline epistles and the others as catholic epistles.

Pseudepigrapha are falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past. The name of the author to whom the work is falsely attributed is often prefixed with the particle "pseudo-", such as for example "pseudo-Aristotle" or "pseudo-Dionysius": these terms refer to the anonymous authors of works falsely attributed to Aristotle and Dionysius the Areopagite, respectively.

The Apostolic Fathers, also known as the Ante-Nicene Fathers, were core Christian theologians among the Church Fathers who lived in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD who are believed to have personally known some of the Twelve Apostles or to have been significantly influenced by them. Their writings, though widely circulated in early Christianity, were not included in the canon of the New Testament. Many of the writings derive from the same time period and geographical location as other works of early Christian literature which came to be part of the New Testament.

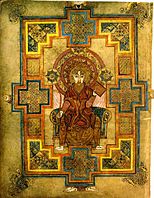

In Christian tradition, the Four Evangelists are Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, the authors attributed with the creation of the four canonical Gospel accounts. In the New Testament, they bear the following titles: the Gospel of Matthew; the Gospel of Mark; the Gospel of Luke; and the Gospel of John.

The New Testament apocrypha are a number of writings by early Christians that give accounts of Jesus and his teachings, the nature of God, or the teachings of his apostles and of their lives. Some of these writings were cited as scripture by early Christians, but since the fifth century a widespread consensus has emerged limiting the New Testament to the 27 books of the modern canon. Roman Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Protestant churches generally do not view the New Testament apocrypha as part of the Bible.

The authorship of the Johannine works has been debated by biblical scholars since at least the 2nd century AD. The debate focuses mainly on the identity of the author(s), as well as the date and location of authorship of these writings.

The Johannine epistles, the Epistles of John, or the Letters of John are the First Epistle of John, the Second Epistle of John, and the Third Epistle of John, three of the catholic epistles in the New Testament. In content and style they resemble the Gospel of John. Specifically in the First Epistle of John, Jesus is identified with the divine Christ, and more than in any other New Testament text, God's love of humanity is emphasised.

John of Patmos is the name traditionally given to the author of the Book of Revelation. Revelation 1:9 states that John was on Patmos, an Aegean island off the coast of Roman Asia, where according to most biblical historians, he was exiled as a result of anti-Christian persecution under the Roman emperor Domitian.

Johannine literature is the collection of New Testament works that are traditionally attributed to John the Apostle, John the Evangelist, or to the Johannine community. They are usually dated to the period c. AD 60–110, with a minority of scholars, including Anglican bishop John Robinson, offering the earliest of these datings.

The term Johannine community refers to an ancient Christian community which placed great emphasis on the teachings of Jesus and his apostle John.

Saint Peter, also known as Peter the Apostle, Simon Peter, Simeon, Simon, or Cephas, was one of the Twelve Apostles of Jesus Christ and one of the first leaders of the early Christian Church. He appears repeatedly and prominently in all four New Testament gospels as well as the Acts of the Apostles. Catholic tradition accredits Peter as the first bishop of Rome—or pope—and also as the first bishop of Antioch.

The name John is prominent in the New Testament and occurs numerous times. Among Jews of this period, the name was one of the most popular, borne by about five percent of men. Thus, it has long been debated which Johns are to be identified with which.