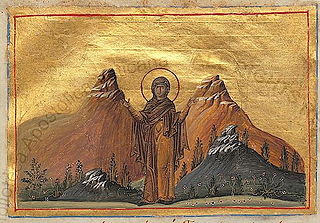

Anthony the Great was a Christian monk from Egypt, revered since his death as a saint. He is distinguished from other saints named Anthony, such as Anthony of Padua, by various epithets: Anthony of Egypt, Anthony the Abbot, Anthony of the Desert, Anthony the Anchorite, Anthony the Hermit, and Anthony of Thebes. For his importance among the Desert Fathers and to all later Christian monasticism, he is also known as the Father of All Monks. His feast day is celebrated on 17 January among the Eastern Orthodox and Catholic churches and on Tobi 22 in the Coptic calendar.

A hermit, also known as an eremite or solitary, is a person who lives in seclusion. Eremitism plays a role in a variety of religions.

Benedict of Aniane, born Witiza and called the Second Benedict, was a Benedictine monk and monastic reformer who had a substantial impact on the religious practice of the Carolingian Empire. His feast day is either February 11 or 12, depending on the liturgical calendar.

Moses the Black, also known as Moses the Strong, Moses the Robber, and Moses the Ethiopian, was an ascetic hieromonk in Egypt in the fourth century AD, and a Desert Father. He is highly venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church and the Oriental Orthodox Church. According to stories about him, he converted from a life of crime to one of asceticism. He is mentioned in Sozomen's Ecclesiastical History, written about 70 years after Moses's death.

Onuphrius lived as a hermit in the desert of Upper Egypt in the 4th or 5th centuries. He is venerated as Saint Onuphrius in both the Roman Catholic and Eastern Catholic churches, as Venerable Onuphrius in Eastern Orthodoxy, and as Saint Nofer the Anchorite in Oriental Orthodoxy.

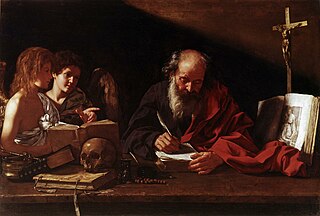

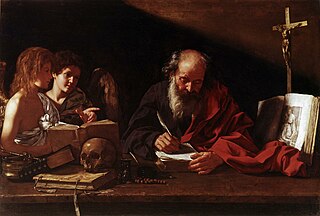

Christian monasticism is a religious way of life of Christians who live ascetic and typically cloistered lives that are dedicated to Christian worship. It began to develop early in the history of the Christian Church, modeled upon scriptural examples and ideals, including those in the Old Testament. It has come to be regulated by religious rules and, in modern times, the Canon law of the respective Christian denominations that have forms of monastic living. Those living the monastic life are known by the generic terms monks (men) and nuns (women). The word monk originated from the Greek μοναχός, itself from μόνος meaning 'alone'.

Thecla was a saint of the early Christian Church, and a reported follower of Paul the Apostle. The earliest record of her life comes from the ancient apocryphal Acts of Paul and Thecla.

September 24 - Eastern Orthodox liturgical calendar - September 26

Melania the Elder, Latin Melania Maior was a Desert Mother who was an influential figure in the Christian ascetic movement that sprang up in the generation after the Emperor Constantine made Christianity a legal religion of the Roman Empire. She was a contemporary of, and well known to, Abba Macarius and other Desert Fathers in Egypt, Jerome, Augustine of Hippo, Paulinus of Nola, and Evagrius of Pontus, and she founded two religious communities on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem. She stands out for the convent she founded for herself and the monastery she established in honour of Rufinus of Aquileia, which belongs to the earliest Christian communities, and because she promoted the asceticism which she, as a follower of Origen, considered indispensable for salvation.

Anthony of Kiev, also called Anthony of the Caves, was a monk and the founder of the monastic tradition in Kievan Rus'. Together with Theodosius of Kiev, he co-founded the Kiev Pechersk Lavra.

Pelagia, distinguished as Pelagia of Antioch, Pelagia the Penitent, and Pelagia the Harlot, was a Christian saint and hermit in the 4th or 5th century. Her feast day was celebrated on 8 October, originally in common with Saints Pelagia the Virgin and Pelagia of Tarsus. Pelagia died as a result of extreme asceticism, which had emaciated her to the point she could no longer be recognized. According to Orthodox tradition, she was buried in her cell. Upon the discovery that the renowned monk had been a woman, the holy fathers tried to keep it a secret, but the gossip spread and her relics drew pilgrims from as far off as Jericho and the Jordan valley.

Saint Anastasia the Patrician was a Byzantine courtier and later saint. She was a lady-in-waiting to the Byzantine empress Theodora. Justinian I, Theodora's husband, may have pursued her, as Theodora grew jealous of her. Anastasia, to avoid any trouble, left for Alexandria in Egypt. She arrived at a place called Pempton, near Alexandria, where she founded a monastery which would later be named after her. She lived with monastic discipline and wove cloth to support herself.

Marcellina was born in Trier, Gaul the daughter of the Praetorian prefect of Gaul, and was the elder sister of Ambrose of Milan and Satyrus of Milan. Marcellina devoted her life as a consecrated virgin to the practice of prayer and asceticism. Her feast is on 17 July.

Marina, distinguished as Marina the Monk and also known as Marinos, Pelagia and Mary of Alexandria, was a Christian saint from part of Asian Byzantium, generally said to be present-day Lebanon. Details of the saint's life vary.

St. Thaïs, of fourth-century Roman Alexandria and of the Egyptian desert, was a repentant courtesan.

Theodora of Alexandria was a saint and martyr who lived during the 5th century in Alexandria, during the reign of Emperor Zeno. Hagiographer Sabine Baring-Gould states that Theodora's story might have been embellished and that her biography was probably pieced together from the lives of other saints, such as Marina the Monk, another 5th century Byzantine saint who also lived as a male among monks, was accused of the same things as Theodora, and was vindicated after her death.

Desert Mothers is a neologism, coined in feminist theology as an analogy to Desert Fathers, for the ammas or female Christian ascetics living in the desert of Egypt, Palestine, and Syria in the 4th and 5th centuries AD. They typically lived in the monastic communities that began forming during that time, though sometimes they lived as hermits. Monastic communities acted collectively with limited outside relations with lay people. Some ascetics chose to venture into isolated locations to restrict relations with others, deepen spiritual connection, and other ascetic purposes. Other women from that era who influenced the early ascetic or monastic tradition while living outside the desert are also described as Desert Mothers.

Apollinaris Syncletica, also known as Apollinaria of Egypt, was a saint and hermit of the 5th century, venerated in the Eastern Orthodox Church and Roman Catholic Church. Her story is most likely apocryphal and "turns on the familiar theme of a girl putting on male attire and living for many years undiscovered".

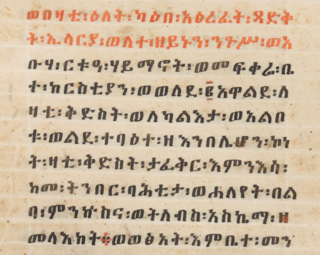

The Legend of Hilaria is a Coptic romance, possibly a Christian version of the pagan Tale of Bentresh. It was written between the 6th and 9th centuries. During the Middle Ages, it was translated into Syriac, Arabic and Ethiopic. It tells the tale of Hilaria, daughter of the Roman emperor Zeno, who disguised herself as a man to become a monk and later heals her sister of an ailment. The tale was incorporated into the synaxaries of the Oriental Orthodox churches, and Hilaria came to be celebrated as a saint.