Southern Schleswig is the southern half of the former Duchy of Schleswig in Germany on the Jutland Peninsula. The geographical area today covers the large area between the Eider river in the south and the Flensburg Fjord in the north, where it borders Denmark. Northern Schleswig, congruent with the former South Jutland County, forms the southernmost part of Denmark. The area belonged to the Crown of Denmark until Prussia and Austria declared war on Denmark in 1864. Denmark wanted to give away the German-speaking Holsten and set the new border at the small river Ejderen. Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck concluded that this justified a war, and even proclaimed it a "holy war". He also turned to the Emperor of Austria, Franz Joseph I of Austria for help. A similar war in 1848 had gone poorly for the Prussians. With Prussia's modern weapons and the help from both the Austrians and General Moltke, the Danish army was destroyed or forced to make a disorderly retreat. The Prussian-Danish border was then moved from the Elbe up in Jutland to the Kongeåen creek.

The Duchy of Schleswig was a duchy in Southern Jutland covering the area between about 60 km north and 70 km (45 mi) south of the current border between Germany and Denmark. The territory has been divided between the two countries since 1920, with Northern Schleswig in Denmark and Southern Schleswig in Germany. The region is also called Sleswick in English.

The German Confederation was an association of 39 predominantly German-speaking sovereign states in Central Europe. It was created by the Congress of Vienna in 1815 as a replacement of the former Holy Roman Empire, which had been dissolved in 1806 as a result of the Napoleonic Wars.

The history of Schleswig-Holstein consists of the corpus of facts since the pre-history times until the modern establishing of the Schleswig-Holstein state.

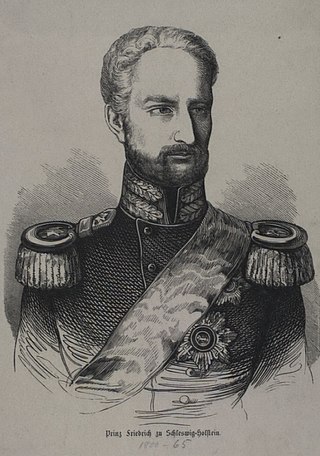

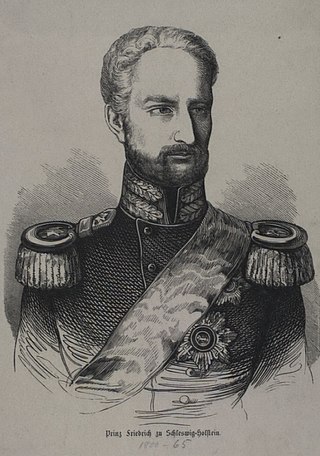

Frederick VIII, Duke of Schleswig-Holstein and of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg was the German pretender to the throne of second duke of Schleswig-Holstein from 1863, although in reality Prussia took overlordship and real administrative power.

The First Schleswig War, also known as the Schleswig-Holstein Uprising and the Three Years' War, was a military conflict in southern Denmark and northern Germany rooted in the Schleswig-Holstein Question: who should control the Duchies of Schleswig, Holstein and Lauenburg, which at the time were ruled by the king of Denmark in a personal union. Ultimately, the Danish side proved victorious with the diplomatic support of the great powers, especially Britain and Russia, since the duchies were close to an important Baltic seaway connecting both powers.

The Second Schleswig War, also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War, was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. The war began on 1 February 1864, when Prussian and Austrian forces crossed the border into the Danish fief Schleswig. Denmark fought troops of the Kingdom of Prussia and the Austrian Empire representing the German Confederation.

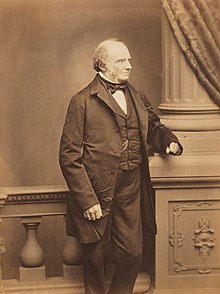

Count Friedrich Ferdinand von Beust was a German and Austrian statesman. As an opponent of Otto von Bismarck, he attempted to conclude a common policy of the German middle states between Austria and Prussia.

The Schleswig–Holstein question was a complex set of diplomatic and other issues arising in the 19th century from the relations of two duchies, Schleswig and Holstein, to the Danish Crown, to the German Confederation, and to each other.

The Gastein Convention, also called the Convention of Badgastein, was a treaty signed at Bad Gastein in Austria on 14 August 1865. It embodied agreements between the two principal powers of the German Confederation, Prussia and Austria, over the governing of the 'Elbe Duchies' of Schleswig, Holstein and Saxe-Lauenburg.

The Battle of Dybbøl was the key battle of the Second Schleswig War, fought between Denmark and Prussia. The battle was fought on the morning of 18 April 1864, following a siege that began on 2 April. Denmark suffered a severe defeat which – with the Prussian capture of the island of Als – ultimately decided the outcome of the war, forcing Danish cession of the duchies of Schleswig and Holstein.

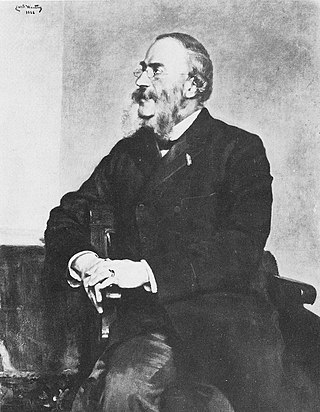

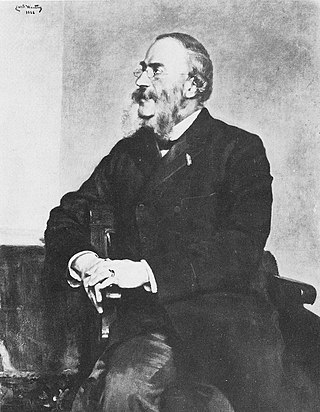

Gerson von Bleichröder was a Jewish German banker. He was also a close confidant of Otto von Bismarck, serving as his financial agent. He became the first non-converted Jew in Prussia to be granted a hereditary title of nobility.

The Schleswig plebiscites were two plebiscites, organized according to section XII, articles 109 to 114 of the Treaty of Versailles of 28 June 1919, in order to determine the future border between Denmark and Germany through the former Duchy of Schleswig. The process was monitored by a commission with representatives from France, the United Kingdom, Norway and Sweden.

The Luxembourg Crisis was a diplomatic dispute and confrontation in 1867 between France and Prussia over the political status of Luxembourg.

The Duchy of Holstein was the northernmost state of the Holy Roman Empire, located in the present German state of Schleswig-Holstein. It originated when King Christian I of Denmark had his County of Holstein-Rendsburg elevated to a duchy by Emperor Frederick III in 1474. Members of the Danish House of Oldenburg ruled Holstein – jointly with the Duchy of Schleswig – for its entire existence.

Prince Frederick Emil August of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg, usually simply known by just his first name, Frederick, Prince of Noer, was a prince of the House of Schleswig-Holstein-Sonderburg-Augustenburg and a cadet-line descendant of the Danish royal house.

On 8 May 1852, after the First War of Schleswig, an agreement called the London Protocol was signed. This international treaty was the revision of an earlier protocol, which had been ratified on 2 August 1850, by the major German powers of Austria and Prussia. The second London Protocol was recognised by the five major European powers—Austria, France, Prussia, Russia, and the United Kingdom—as well as by the Baltic Sea powers of Denmark and Sweden.

Wanke nicht, mein Vaterland, also known as Schleswig-Holstein, meerumschlungen or Schleswig-Holstein-Lied is the unofficial anthem of Schleswig-Holstein. It was written in 1844 and presented at the Schleswiger Sängerfest. The tune was written by Carl Gottlieb Bellmann (1772–1862). The text had originally been written by Berlin-based lawyer Karl Friedrich Straß (1803–1864) but rewritten by Matthäus Friedrich Chemnitz (1815–1870) shortly before the start of the Sängerfest in order to represent the then atmosphere in a better way. The song expresses the wish for a united, independent and German Schleswig-Holstein.

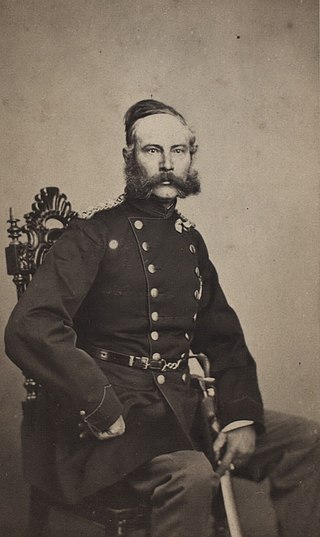

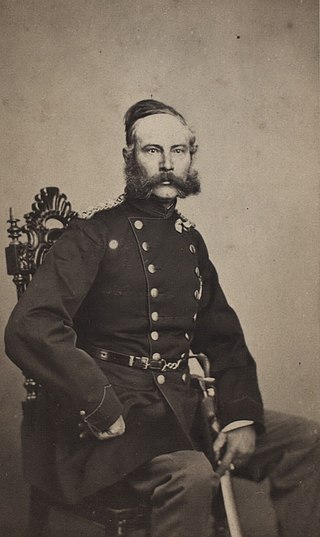

Carl Philip Friedemann Maximilian Müller, more commonly known as Max Müller was a Danish officer who served in the First and Second Schleswig Wars.

The Danish Unitary State was a Danish political designation for the monarchical state formation of Denmark, Schleswig, Holstein, and Saxe-Lauenburg, between the two treaties of Vienna in 1815 and 1864. The usage of the term became relevant after the First Schleswig War, when a need for a constitutional framework for the monarchy was present, which ought to follow the premises of the London Protocol, which prohibited a closer connection between two of the monarchy's possessions. The political designation was ultimately eliminated after The Second Schleswig War and was replaced by the national state in 1866.