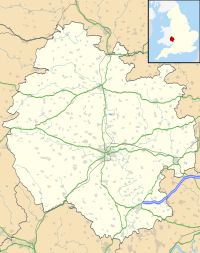

Hereford is a cathedral city and the county town of Herefordshire, England. It lies on the River Wye, approximately 16 miles (26 km) east of the border with Wales, 24 miles (39 km) south-west of Worcester and 23 miles (37 km) north-west of Gloucester. With a population of 53,112 in 2021, it is the largest settlement in Herefordshire.

Worcester is a cathedral city in Worcestershire, England, of which it is the county town. It is 30 mi (48 km) south-west of Birmingham, 27 mi (43 km) north of Gloucester and 23 mi (37 km) north-east of Hereford. The population was 103,872 in the 2021 census.

Stokesay Castle is one of the finest surviving fortified manor houses in England, and situated at Stokesay in Shropshire. It was largely built in its present form in the late 13th century by Laurence of Ludlow, on the earlier castle founded by its original owners the de Lacy family, from whom it passed to their de Verdun heirs, who retained feudal overlordship of Stokesay until at least 1317. Laurence 'of' Ludlow was one of the leading wool merchants in England, who intended it to form a secure private house and generate income as a commercial estate. Laurence's descendants continued to own the castle until the 16th century, when it passed through various private owners. By the time of the outbreak of the First English Civil War in 1642, Stokesay was owned by William Craven, 1st Earl of Craven (1608–1697), a supporter of King Charles I. After the Royalist war effort collapsed in 1645, Parliamentary forces besieged the castle in June and quickly forced its garrison to surrender. Parliament ordered the property to be slighted, but only minor damage was done to the walls, allowing Stokesay to continue to be used as a house by the Baldwyn family until the end of the 17th century.

Leominster is a market town in Herefordshire, England; it is located at the confluence of the River Lugg and its tributary the River Kenwater. The town is 12 miles north of Hereford and 7 miles south of Ludlow in Shropshire. With a population of 11,700, Leominster is the largest of the five towns in the county; the others being Ross-on-Wye, Ledbury, Bromyard and Kington.

The history of Herefordshire starts with a shire in the time of King Athelstan, and Herefordshire is mentioned in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 1051. The first Anglo-Saxon settlers, the 7th-century Magonsætan, were a sub-tribal unit of the Hwicce who occupied the Severn valley. The Magonsætan were said to be in the intervening lands between the Rivers Wye and Severn. The undulating hills of marl clay were surrounded by the Welsh mountains to the west; by the Malvern Hills to the east; by the Clent Hills of the Shropshire borders to the north, and by the indeterminate extent of the Forest of Dean to the south. The shire name first recorded in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle may derive from "Here-ford", Old English for "army crossing", the location for the city of Hereford.

Leigh is a village and civil parish in the Malvern Hills district of the county of Worcestershire, England.

Wychbold is a village in the Wychavon district of Worcestershire. The village is situated on the A38 between Droitwich Spa and Bromsgrove, and by Junction 5 of the M5 motorway.

de Lacy is the surname of an old Norman family which originated from Lassy, Calvados. The family took part in the Norman Conquest of England and the later Norman invasion of Ireland. The name is first recorded for Hugh de Lacy (1020–1085). His sons, Walter and Ilbert, left Normandy and travelled to England with William the Conqueror. The awards of land by the Conqueror to the de Lacy sons led to two distinct branches of the family: the northern branch, centred on Blackburnshire and west Yorkshire was held by Ilbert's descendants; the southern branch of Marcher Lords, centred on Herefordshire and Shropshire, was held by Walter's descendants.

Hartlebury Castle, a Grade I listed building, near Hartlebury in Worcestershire, central England, was built in the mid-13th century as a fortified manor house, on manorial land earlier given to the Bishop of Worcester by King Burgred of Mercia. It lies near Stourport-on-Severn in an area with several large manors and country houses, including Witley Court, Astley Hall, Pool House, Areley Hall and Hartlebury and Abberley Hall. Later, it became the bishop's principal residence.

British Camp is an Iron Age hill fort located at the top of Herefordshire Beacon in the Malvern Hills. The hill fort is protected as a Scheduled Ancient Monument and is owned and maintained by Malvern Hills Conservators. The fort is thought to have been first constructed in the 2nd century BC. A Norman castle was built on the site.

Bewdley Bridge is a three-span masonry arch bridge over the River Severn at Bewdley, Worcestershire, designed by civil engineer Thomas Telford. The two side spans are each 52 feet (16 m), with the central span 60 feet (18 m). The central arch rises 18 feet (5.5 m). Smaller flood arches on the bank bridge the towpath. The bridge is 27 feet (8.2 m) wide.

Ewyas was a possible early Welsh kingdom which may have been formed around the time of the Roman withdrawal from Britain in the 5th century. The name was later used for a much smaller commote or administrative sub-division, which covered the area of the modern Vale of Ewyas and a larger area to the east including the villages of Ewyas Harold and Ewyas Lacy.

Roger Mortimer, 1st Baron Mortimer of Chirk was a 14th-century Marcher lord, notable for his opposition to Edward II of England during the Despenser War.

Berkhamsted Castle is a Norman motte-and-bailey castle in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire. The castle was built to obtain control of a key route between London and the Midlands during the Norman conquest of England in the 11th century. Robert of Mortain, William the Conqueror's half brother, was probably responsible for managing its construction, after which he became the castle's owner. The castle was surrounded by protective earthworks and a deer park for hunting. The castle became a new administrative centre of the former Anglo-Saxon settlement of Berkhamsted. Subsequent kings granted the castle to their chancellors. The castle was substantially expanded in the mid-12th century, probably by Thomas Becket.

Pain fitzJohn was an Anglo-Norman nobleman and administrator, one of King Henry I of England's "new men", who owed their positions and wealth to the king.

Worcester's early importance is partly due to its position on trade routes, but also because it was a centre of Church learning and wealth, due to the very large possessions of the See and Priory accumulated in the Anglo-Saxon period. After the reformation, Worcester continued as a centre of learning, with two early grammar schools with strong links to Oxford University.

Castle Frome is a village and civil parish in the county of Herefordshire, England, and is 10 miles (16 km) north-east from the city and county town of Hereford. The closest large town is the market town of Bromyard, 5 miles (8 km) to the north. The Norman font in Castle Frome church is "one of the outstanding works of the Herefordshire school".

Llancillo is a civil parish in south-west Herefordshire, England, and is approximately 13 miles (20 km) south-west from Hereford. The parish borders Wales at the south in which is the nearest town, Abergavenny, 7 miles (11 km) to the south-southwest. In the parish is the isolated Grade II* listed 11th-century Church of St Peter.