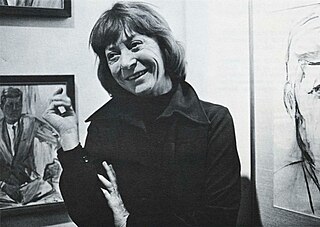

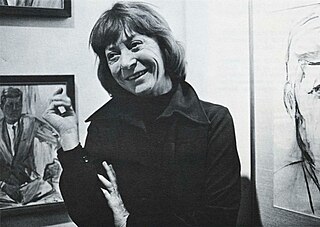

Elaine Marie Catherine de Kooning was an Abstract Expressionist and Figurative Expressionist painter in the post-World War II era. She wrote extensively on the art of the period and was an editorial associate for Art News magazine.

Maria Helena Vieira da Silva was a Portuguese abstract painter. She was considered a leading member of the European abstract expressionism movement known as Art Informel. Her works feature complex interiors and city views using lines that explore space and perspective. She also worked in tapestry and stained glass.

Ethel Kremer Schwabacher was an influential abstract expressionist painter, represented by the Betty Parsons Gallery in the 1950s and 1960s. She was a protégé and first biographer of Arshile Gorky, and friends with many of the prominent painters of New York at that time, including Willem de Kooning, Richard Pousette-Dart, Kenzo Okada, and José Guerrero. She was also the author of a monograph on the artist John Charles Ford and a memoir, "Hungry for Light".

Alma Woodsey Thomas was an African-American artist and teacher who lived and worked in Washington, D.C., and is now recognized as a major American painter of the 20th century. Thomas is best known for the "exuberant", colorful, abstract paintings that she created after her retirement from a 35-year career teaching art at Washington's Shaw Junior High School.

Miriam Schapiro was a Canadian-born artist based in the United States. She was a painter, sculptor, printmaker, and a pioneer of feminist art. She was also considered a leader of the Pattern and Decoration art movement. Schapiro's artwork blurs the line between fine art and craft. She incorporated craft elements into her paintings due to their association with women and femininity. Schapiro's work touches on the issue of feminism and art: especially in the aspect of feminism in relation to abstract art. Schapiro honed in her domesticated craft work and was able to create work that stood amongst the rest of the high art. These works represent Schapiro's identity as an artist working in the center of contemporary abstraction and simultaneously as a feminist being challenged to represent women's "consciousness" through imagery. She often used icons that are associated with women, such as hearts, floral decorations, geometric patterns, and the color pink. In the 1970s she made the hand fan, a typically small woman's object, heroic by painting it six feet by twelve feet. "The fan-shaped canvas, a powerful icon, gave Schapiro the opportunity to experiment … Out of this emerged a surface of textured coloristic complexity and opulence that formed the basis of her new personal style. The kimono, fans, houses, and hearts were the form into which she repeatedly poured her feelings and desires, her anxieties, and hopes".

Dannielle Tegeder is a contemporary artist who works with installation, animation and sound and is best known for her abstract paintings and drawings. She lives in Brooklyn, New York and maintains a studio at The Elizabeth Foundation in Times Square, Manhattan.

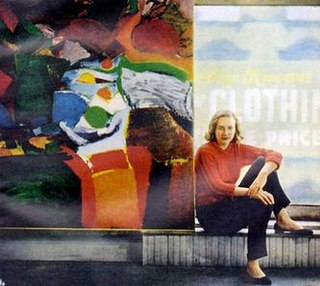

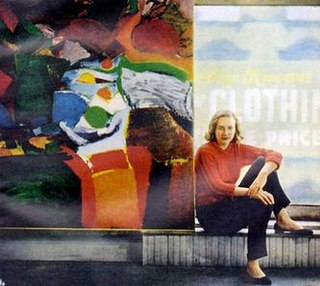

Grace Hartigan was an American Abstract Expressionist painter and a significant member of the vibrant New York School of the 1950s and 1960s. Her circle of friends, who frequently inspired one another in their artistic endeavors, included Jackson Pollock, Larry Rivers, Helen Frankenthaler, Willem and Elaine de Kooning and Frank O'Hara. Her paintings are held by numerous major institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. As director of the Maryland Institute College of Art's Hoffberger School of Painting, she influenced numerous young artists.

Katherine Bradford, née Houston, is an American artist based in New York City, known for figurative paintings, particularly of swimmers, that critics describe as simultaneously representational, abstract and metaphorical. She began her art career relatively late and has received her widest recognition in her seventies. Critic John Yau characterizes her work as independent of canon or genre dictates, open-ended in terms of process, and quirky in its humor and interior logic.

Valerie Jaudon is an American painter commonly associated with various Postminimal practices – the Pattern and Decoration movement of the 1970s, site-specific public art, and new tendencies in abstraction.

Barbara Takenaga is an American artist known for swirling, abstract paintings that have been described as psychedelic and cosmic, as well as scientific, due to their highly detailed, obsessive patterning. She gained wide recognition in the 2000s, as critics such as David Cohen and Kenneth Baker placed her among a leading edge of artists renewing abstraction with paintings that emphasized visual beauty and excess, meticulous technique, and optical effects. Her work suggests possibilities that range from imagined landscapes and aerial maps to astronomical and meteorological phenomena to microscopic views of cells, aquatic creatures or mineral cross-sections. In a 2018 review, The New Yorker described Takenaga as "an abstractionist with a mystic’s interest in how the ecstatic can emerge from the laborious."

Alice Trumbull Mason (1904–1971) was an American artist, writer, and a founding member of the American Abstract Artists group (AAA) in New York City. Mason was recognized as a pioneer of American Abstract Art.

Karin Davie is a contemporary artist who lives and works in New York City and Seattle, Washington.

Clare E. Rojas, also known by stage name Peggy Honeywell, is an American multidisciplinary artist. She is part of the Mission School. Rojas is "known for creating powerful folk-art-inspired tableaus that tackle traditional gender roles." She works in a variety of media, including painting, installations, video, street art, and children's books. Rojas lives in the San Francisco Bay Area.

Polly E. Apfelbaum is an American contemporary visual artist, who is primarily known for her colorful drawings, sculptures, and fabric floor pieces, which she refers to as "fallen paintings". She currently lives and works in New York City, New York.

Candida Alvarez is an American artist and professor, known for her paintings and drawings.

Judith Murray is an American abstract painter based in New York City. Active since the 1970s, she has produced a wide-ranging, independent body of work while strictly adhering to idiosyncratic, self-imposed constants within her practice. Since 1975, she has limited herself to a primary palette of red, yellow, black and white paints—from which she mixes an infinite range of hues—and a near-square, horizontal format offset by a vertical bar painted along the right edge of the canvas; the bar serves as a visual foil for the rest of the work and acknowledges each painting’s boundary and status as an abstract object. Critic Lilly Wei describes Murray's work as "an extended soliloquy on how sensation, sensibility, and digressions can still be conveyed through paint" and how by embracing the factual world the "abstract artist can construct a supreme and sustaining fiction."

Jackie Saccoccio was an American abstract painter. Her works, considered examples of gestural abstraction, featured bright color, large canvases, and deliberately introduced randomness.

Caroline Kent is an American visual artist based in Chicago, best known for her large scale abstract painting works that explore the interplay between language and translation. Inspired by her own personal experiences and her cultural heritage, Kent creates paintings that explore the power and limitations of communication. Her work, influenced by her Mexican heritage, delves into the potentials and confines of language and reconsiders the modernist canon of abstraction. She likens her composition process to choreography, revealing an interconnectedness between language, abstraction, and painting. Kent's artwork showcases an evolving dialogue of space, matter, and time, resulting in a confluence of drawings, paintings, sculpture, and performance, blurring the lines between these mediums.

Lee Hall was an American painter, writer, educator, and a university president. She was an abstract landscape painter. She served as the 13th president of Rhode Island School of Design (RISD). In 1993, Hall wrote a controversial book on the artists Willem de Kooning and Elaine de Kooning.

Wendy Edwards is an American artist known for vibrant, tactile paintings rooted in organic forms and landscape, which have ranged from representation and figuration to free-form abstraction. Her work has been strongly influenced by the 1970s Pattern and Decoration movement and its embrace of ornamentation, repetition, edge-to-edge composition, sensuality and a feminist vision grounded in women's life experience. Critics note in Edwards's paintings an emphasis on surfaces and the materiality of paint, a rhythmic use of linear or geometric elements, and an intuitive orientation toward action, response and immediacy rather than premeditation. In a 2020 review, Boston Globe critic Cate McQuaid wrote, "Edwards's pieces are exuberant, edgy, and thoughtful … [her] sweet, tart colors and delicious textures make the senses a gateway into larger notions about women and men, creation and mortality."