Related Research Articles

Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 7th Earl of Shaftesbury, styled Lord Ashley from 1811 to 1851, was a British Tory politician, philanthropist, and social reformer. He was the eldest son of the 6th Earl of Shaftesbury and Lady Anne Spencer, and elder brother of Henry Ashley, MP. A social reformer who was called the "Poor Man's Earl", he campaigned for better working conditions, reform to lunacy laws, education and the limitation of child labour. He was also an early supporter of the Zionist movement and the YMCA and a leading figure in the evangelical movement in the Church of England.

James Martineau was a British religious philosopher influential in the history of Unitarianism.

Harriet Martineau was an English social theorist often seen as the first female sociologist. She wrote from a sociological, holistic, religious and feminine angle, translated works by Auguste Comte, and, rarely for a woman writer at the time, earned enough to support herself. The young Princess Victoria enjoyed her work and invited her to her 1838 coronation. Martineau advised "a focus on all [society's] aspects, including key political, religious, and social institutions". She applied thorough analysis to women's status under men. The novelist Margaret Oliphant called her "a born lecturer and politician... less distinctively affected by her sex than perhaps any other, male or female, of her generation."

Barnwood House Hospital was a private mental hospital in Barnwood, Gloucester, England. It was founded by the Gloucester Asylum Trust in 1860 as Barnwood House Institution and later became known as Barnwood House Hospital. The hospital catered for well-to-do patients, with reduced terms for those in financial difficulties. It was popular with the military and clergy, and once counted an archbishop amongst its patients. During the late nineteenth century Barnwood House flourished under superintendent Frederick Needham, making a healthy profit and receiving praise from the Commissioners in Lunacy. Even the sewerage system was held up as a model of good asylum practice. After the First World War service patients, including war poet and composer Ivor Gurney, were treated with a regime of psychotherapy and recreations such as cricket.

The Agapemonites or Community of The Son of Man was a Christian religious group or sect that existed in England from 1846 to 1956. It was named from the Greek: agapemone meaning "abode of love". The Agapemone community was founded by the Reverend Henry Prince in Spaxton, Somerset. The sect also built a church in Upper Clapton, London, and briefly had bases in Stoke-by-Clare in Suffolk, Brighton and Weymouth.

Fulbourn Hospital is a mental health facility located between the Cambridgeshire village of Fulbourn and the Cambridge city boundary at Cherry Hinton, about 5 miles (8 km) south-east of the city centre. It is managed by the Cambridgeshire and Peterborough NHS Foundation Trust. The Ida Darwin Hospital site is situated behind Fulbourn Hospital. It is run and managed by the same trust, with both hospitals sharing the same facilities and staff pool.

The Woman in White is Wilkie Collins's fifth published novel, written in 1860 and set from 1849 to 1850. It started its publication on 26 November 1859 and its publication was completed on 25 August 1860. It is a mystery novel and falls under the genre of "sensation novels".

Thomas Michael Greenhow MD MRCS FRCS was an English surgeon and epidemiologist.

Robert Gardiner Hill MD was a British surgeon specialising in the treatment of lunacy. He is normally credited with being the first superintendent of a small asylum to develop a mode of treatment in which reliance on mechanical medical restraint and coercion could be dropped altogether. In practice he reached this situation in 1838.

The bibliography of Charles Dickens (1812–1870) includes more than a dozen major novels, many short stories, several plays, several non-fiction books, and individual essays and articles. Dickens's novels were serialized initially in weekly or monthly magazines, then reprinted in standard book formats.

The Commissioners in Lunacy or Lunacy Commission were a public body established by the Lunacy Act 1845 to oversee asylums and the welfare of mentally ill people in England and Wales. It succeeded the Metropolitan Commissioners in Lunacy.

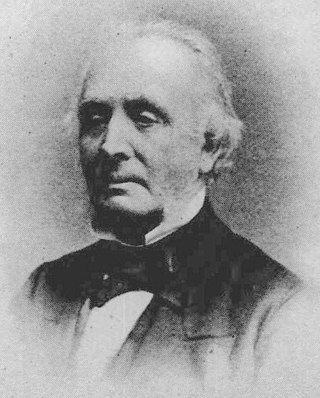

John Thomas Perceval was a British army officer who was confined in lunatic asylums for three years and spent the rest of his life campaigning for reform of the lunacy laws and for better treatment of asylum inmates. He was one of the founders of the Alleged Lunatics' Friend Society and acted as their honorary secretary for about twenty years. Perceval's two books about his experience in asylums were republished by anthropologist Gregory Bateson in 1962, and in recent years he has been hailed as a pioneer of the mental health advocacy movement.

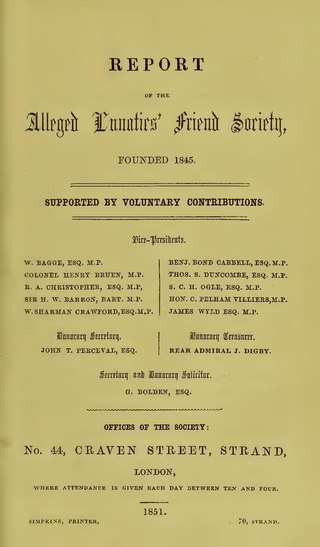

The Alleged Lunatics' Friend Society was an advocacy group started by former asylum patients and their supporters in 19th-century Britain. The Society campaigned for greater protection against wrongful confinement or cruel and improper treatment, and for reform of the lunacy laws. The Society is recognised today as a pioneer of the psychiatric survivors movement.

The lunatic asylum, insane asylum or mental asylum was an early precursor of the modern psychiatric hospital.

Harriet Sarah, Lady Mordaunt was the Scottish wife of an English baronet and member of parliament, Sir Charles Mordaunt. She was the respondent in a sensational divorce case in which the Prince of Wales was embroiled, and after a counter-petition led to a finding of mental disorder she spent the remaining 36 years of her life out of sight in a series of privately rented houses, and then in various private lunatic asylums, finally ending her days in Sutton, Surrey.

Forbes Benignus Winslow DCL, FRCP Edin., MRCP, MRCS, MD, was a British psychiatrist, author and an authority on lunacy during the Victorian era.

Louisa, Countess of Craven, originally Louisa Brunton (1782–1860) was an English actress.

Frances Elizabeth Lupton was an Englishwoman of the Victorian era who worked to open up educational opportunities for women. She married into the politically active Lupton family of Leeds, where she co-founded Leeds Girls' High School in 1876 and was the Leeds representative of the North of England Council for Promoting the Higher Education of Women.

John Stevenson Bushnan (1807–1884) was an English physician and medical writer.

Sir Samuel Fludyer, 3rd Baronet (1800–1876) was the grandson of the first Baronet, Sir Samuel Fludyer, who was reckoned at the time of his death to be the richest man in the country with a wealth of £900,000. He was the only son of Sir Samuel Brudenell Fludyer, who inherited most of the first Sir Samuel's fortune, and had his children painted by Thomas Lawrence, the foremost portrait painter of the time, indicating the family's wealth and social standing. The portrait shows Sir Samuel between his sisters Maria and Carolina Louisa.

References

- ↑

- Scull, Andrew T. Social Order/Mental Disorder: Anglo-American Psychiatry in Historical Perspective. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989.

- Scull, Andrew T. The Theory and Practice of Civil commitment. Michigan Law Review 82:101-117 (1984) via JSTOR. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- ↑

- Mitchell, Sally. Frances Power Cobbe: Victorian Feminist, Journalist, Reformer. Charlottesville (Va): University of Virginia Press, 2004.

- Loewenthal, Kate Miriam. The Psychology of Religion: A Short Introduction. Oxford: Oneworld, 2000

- ↑

- McCormick, Donald. Temple of Love. New York: Citadel Press, 1965

- Knox, Ronald Arbuthnott. Enthusiasm: A Chapter in the History of Religion: with Special Reference to the XVII and XVIII Centuries. Oxford: Oxford University Press at The Clarendon Press, 1962

- ↑ Essex Record Office, Baptisms at St Mary's Church, Bocking / 1851 Census, place of birth entry, Bocking

- ↑ Dr. Stilwell's History of the Case of Miss Nottidge, The Lancet, July 21, 1849

- ↑ Spiritual Wives, Vol 2, William Hepworth Dixon, 1868

- 1 2 3 4 5 Spiritual Wives,

- ↑ Nottidge v. Ripley and Another (1849), reported in The Times: June 25–27, 1849

- 1 2 3 Nottidge v. Ripley and Another (1849)

- ↑ The Lancet, 21 July 1849

- ↑ Nottidge v. Ripley and Another (1849) / Frances Power Cobbe: Victorian Feminist, Journalist and Reformer, Sally Mitchell, 2004

- ↑ The Household Narrative of Current Events - May 1850, p110, Dickens

- ↑ Nottidge v. Prince (1860), The Times: June 5–9, and July 26, 1860

- ↑ Parry, Edward Abbott. The Drama of the Law. London: T. Fisher Unwin, 1924. p.138+.

- ↑ Biographical Sketches 1852-1875: Barry Cornwall, Harriet Martineau