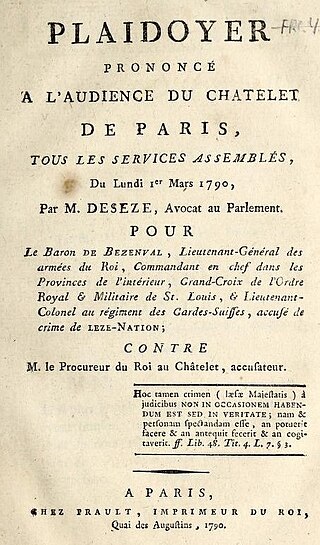

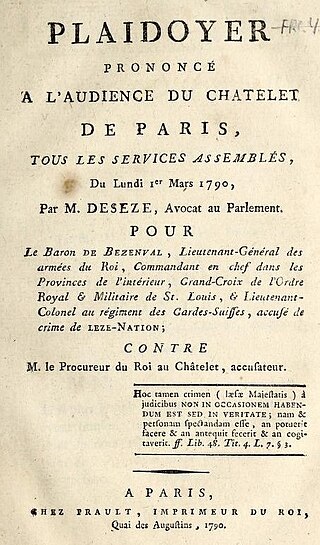

Raymond Romain, Comte de Sèze or Desèze was a French advocate. Together with François Tronchet and Malesherbes, he defended Louis XVI, when the King was brought before the Convention for trial. De Sèze is remembered for a speech on Louis' behalf which impressed even his opponents.

Antoine de Rivarol was a French royalist writer and translator who lived during the Revolutionary era. He was briefly married to the translator Louisa Henrietta de Rivarol.

Louis Philippe, comte de Ségur was a French diplomat and historian.

Jean Joseph Mounier was a French politician and judge.

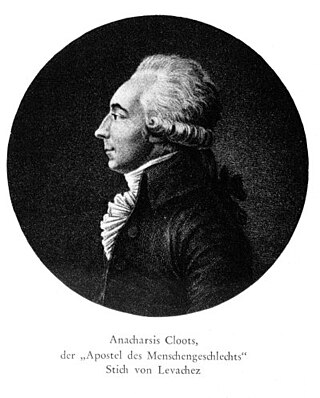

Jean-Baptiste du Val-de-Grâce, baron de Cloots, better known as Anacharsis Cloots, was a Prussian nobleman who was a significant figure in the French Revolution. Perhaps the first to advocate a world parliament, an idea later espoused by Albert Camus and Albert Einstein, he was a world federalist and an internationalist anarchist. He was nicknamed "orator of mankind", "citizen of humanity" and "a personal enemy of God". American author Herman Melville refers to an "Anacharsis Clootz delegation" as a representation of global humanity in both Moby-Dick (1851), The Confidence-Man, and later in Billy Budd.

Thomas de Mahy, Marquis de Favras, was a French aristocrat and supporter of the House of Bourbon during the French Revolution. Often seen as a martyr of the Royalist cause, Favras was executed for his part in "planning against the people of France" under the Count of Provence.

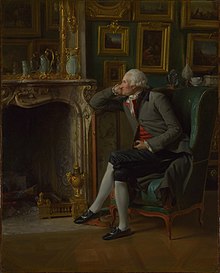

Pierre Victor, baron de Besenval de Brünstatt, also Pierre Victor, baron de Besenval de Brunstatt, was a Swiss military officer in French service.

A closing argument, summation, or summing up is the concluding statement of each party's counsel reiterating the important arguments for the trier of fact, often the jury, in a court case. A closing argument occurs after the presentation of evidence. A closing argument may not contain any new information and may only use evidence introduced at trial. It is not customary to raise objections during closing arguments, except for egregious behavior. However, such objections, when made, can prove critical later in order to preserve appellate issues.

Charles Thévenin was a neoclassical French painter, known for heroic scenes from the time of the French Revolution and First French Empire.

Antoine-François Momoro was a French printer, bookseller and politician during the French Revolution. An important figure in the Cordeliers club and in Hébertisme, he is the originator of the phrase ″Unité, Indivisibilité de la République; Liberté, égalité, fraternité ou la mort″, one of the mottoes of the French Republic.

The Grand Châtelet was a stronghold in Ancien Régime Paris, on the right bank of the Seine, on the site of what is now the Place du Châtelet; it contained a court and police headquarters and a number of prisons.

Joseph Alexandre Pierre, vicomte de Ségur (1756–1805), was a French poet, songwriter, and playwright.

Waldegg Castle, or Schloss Waldegg, is a castle near Solothurn, in the municipality of Feldbrunnen-St. Niklaus of the Canton of Solothurn in Switzerland. It is a Swiss heritage site of national significance.

Pierre-Ulric Dubuisson was an 18th-century French actor, playwright and theatre director.

Jean-Pierre-Louis de Luchet (1740–1792), also known as the Marquis de La Roche du Maine, or Marquis de Luchet, was a French journalist, essayist, and theatre manager.

Jean-Baptiste-Pierre Le Brun was a French painter, art collector and art dealer. Simon Denis was his pupil.

The Hôtel de Besenval is a historic hôtel particulier from the early 18th century in Paris with a cour d'honneur and a large English landscape garden, an architectural style commonly known as entre cour et jardin. This refers to a residence between the courtyard in front of the building and the garden at the back. The building is listed as a Monument historique by decree of 20 October 1928. It has housed the Embassy of the Swiss Confederation and the residence of the Swiss ambassador to France since 1938. The residence is named after its most famous former owner: Pierre Victor, Baron de Besenval de Brunstatt, usually just referred to as Baron de Besenval.

Luc-Vincent Thiéry (1734–1822) was a French lawyer and author, best known for his publications about Paris.

La Gimblette is one of the most famous paintings by the French painter Jean-Honoré Fragonard and one of the most famous Rococo paintings. Like other paintings by Fragonard, such as The Swing,La Gimblette also has a frivolous component.

"The lovers' paradise in the middle of the 18th century is no longer ours at the end of the 20th century. It is therefore not surprising that these pictures remain, in some respects, strange to us."

Victor von Gibelin, also called Beau Gibelin, was a Swiss military officer in French service and a politician in his hometown of Solothurn in Switzerland. He was the last officer of the Swiss Guards under King Louis XVI. He became famous for his friendship with Pierre Victor, Baron de Besenval de Brunstatt, a Swiss military officer in French service from Solothurn, and for his eyewitness report of the events surrounding the Storming of the Palais des Tuileries on 10 August 1792. His report was published posthumously in German and in French in 1866.

"Let's go and see, there's the handsome Gibelin, standing guard!"