1789 (MDCCLXXXIX) was a common year starting on Thursday of the Gregorian calendar and a common year starting on Monday of the Julian calendar, the 1789th year of the Common Era (CE) and Anno Domini (AD) designations, the 789th year of the 2nd millennium, the 89th year of the 18th century, and the 10th and last year of the 1780s decade. As of the start of 1789, the Gregorian calendar was 11 days ahead of the Julian calendar, which remained in localized use until 1923.

Louis XVI was the last king of France before the fall of the monarchy during the French Revolution.

Jeu de paume, nowadays known as real tennis, (US) court tennis or courte paume, is a ball-and-court game that originated in France. It was an indoor precursor of tennis played without racquets, and so "game of the hand", though these were eventually introduced. It is a former Olympic sport, and has the oldest ongoing annual world championship in sport, first established over 250 years ago. The term also refers to the court on which the game is played and its building, which in the 17th century was sometimes converted into a theatre.

The National Constituent Assembly was a constituent assembly in the Kingdom of France formed from the National Assembly on 9 July 1789 during the first stages of the French Revolution. It dissolved on 30 September 1791 and was succeeded by the Legislative Assembly.

The following is a timeline of the French Revolution.

In France under the Ancien Régime, the Estates General or States-General was a legislative and consultative assembly of the different classes of French subjects. It had a separate assembly for each of the three estates, which were called and dismissed by the king. It had no true power in its own right as, unlike the English Parliament, it was not required to approve royal taxation or legislation. It served as an advisory body to the king, primarily by presenting petitions from the various estates and consulting on fiscal policy.

Joseph-Ignace Guillotin was a French physician, politician, and freemason who proposed on 10 October 1789 the use of a device to carry out executions in France, as a less painful method of execution than existing methods. Although he did not invent the guillotine and opposed the death penalty, his name became an eponym for it. The actual inventor of the prototype was a man named Tobias Schmidt, working with the king's physician, Antoine Louis.

This glossary of the French Revolution generally does not explicate names of individual people or their political associations; those can be found in List of people associated with the French Revolution.

The Civil Constitution of the Clergy was a law passed on 12 July 1790 during the French Revolution, that sought the complete control over the Catholic Church in France by the French government. As a result, a schism was created, resulting in an illegal and underground French Catholic Church loyal to the Papacy, and a "constitutional church" that was subservient to the State. The schism was not fully resolved until 1801. King Louis XVI ultimately granted Royal Assent to the measure after originally opposing it, but later expressed regret for having done so.

There is significant disagreement among historians of the French Revolution as to its causes. Usually, they acknowledge the presence of several interlinked factors, but vary in the weight they attribute to each one. These factors include cultural changes, normally associated with the Enlightenment; social change and financial and economic difficulties; and the political actions of the involved parties. For centuries, the French society was divided into three estates or orders.

The French Revolution was a period in the history of France covering the years 1789 to 1799, in which Republicans overthrew the Bourbon monarchy and the Roman Catholic Church perforce underwent radical restructuring. This article covers a period of time slightly longer than a year, from 14 July 1790, the first anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, to the establishment of the Legislative Assembly on 1 October 1791.

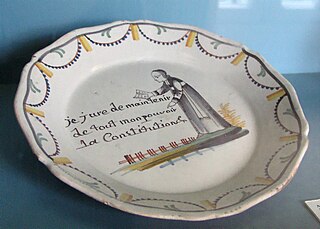

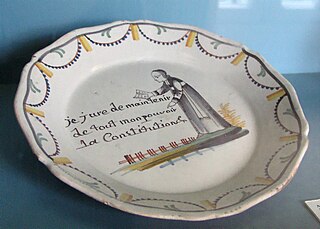

During the French Revolution, the National Assembly abolished the traditional structure of the Catholic Church in France and reorganized it as an institution within the structure of the new French government through the Civil Constitution of the Clergy. One of the new requirements placed upon all clergy was the necessity of an oath of loyalty to the State before all foreign influences such as the Pope. This created a schism within the French clergy, with those taking the oath known as juring priests, and those refusing the oath known as non-juring clergy or refractory clergy.

The Estates General of 1789(French: États Généraux de 1789) was a general assembly representing the French estates of the realm: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. It was the last of the Estates General of the Kingdom of France.

During the French Revolution, the National Assembly, which existed from 17 June 1789 to 9 July 1789, was a revolutionary assembly of the Kingdom of France formed by the representatives of the Third Estate (commoners) of the Estates-General and eventually joined by some members of the First and Second Estates. Thereafter, it became a legislative body known as the National Constituent Assembly, although the shorter form was favored.

The Storming of the Bastille occurred in Paris, France, on 14 July 1789, when revolutionary insurgents attempted to storm and seize control of the medieval armoury, fortress and political prison known as the Bastille. After four hours of fighting and 94 deaths the insurgents were able to enter the Bastille. The governor de Launay and several members of the garrison were killed after surrender. The Bastille then represented royal authority in the centre of Paris. The prison contained only seven inmates at the time of its storming and was already scheduled for demolition, but was seen by the revolutionaries as a symbol of the monarchy's abuse of power. Its fall was the flashpoint of the French Revolution.

La Révolution française is a two-part 1989 historical drama co-produced by France, Germany, Italy and Canada for the 200th anniversary of the French Revolution. The full film runs at 360 minutes, but the edited-for-television version is slightly longer. It purports to tell a faithful and neutral story of the Revolution, from the calling of the Estates-General to the death of Maximilien de Robespierre. The film had a large budget and boasted an international cast. It was shot in French, German and English.

The Tennis Court Oath is an incomplete painting by the French Neoclassical artist Jacques-Louis David, painted between 1790 and 1794 and showing the titular Tennis Court Oath at Versailles, one of the foundational events of the French Revolution.

Louis-François Allard was a French physician and politician.

The Recollects Convent was built originally in 1684 at the Palace of Versailles, France by order of Louis XIV as a house for the religious order of Recollects - a reform branch of the Franciscans created in 16th century in France, Germany, and Holland. After the order was suppressed during the French Revolution, the building was converted into a prison, and then later in the 19th century was used by the French army.

The term "Red Priests" or "Philosopher Priests" is a modern historiographical term that refers to Catholic priests who, to varying degrees, supported the French Revolution (1789-1799). The term "Red Priests" was coined in 1901 by Gilbert Brégail and later adopted by Edmond Campagnac. However, it is anachronistic because the color red, associated with socialist movements since 1848, did not signify supporters of the French Revolution, who were referred to as "Blues" during the civil wars of 1793–1799, in contrast to the royalist "Whites." Hence, a recent historian suggested using the term "Philosopher Priests" to describe this group, a term used at the time to refer to these priests.