Background

The immediate background to the introduction of the Prairial Law was the attempted assassinations of Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois on 23 May and of Maximilien Robespierre on 25 May. Introducing the decree at the Convention, Georges Couthon, who had drafted it, argued that political crimes were far worse than common crimes because in the latter "only individuals are wounded" whereas in the former "the existence of free society is threatened". Under these circumstances, "indulgence is an atrocity... clemency is parricide". [2] The law was an extension of the centralisation and organisation of the Terror, following the decrees of 16 April and 8 May which had suspended the revolutionary court in the provinces and brought all political cases for trial in the capital. [3] The result of these laws was that by June 1794 Paris was full of suspects awaiting trial. On 29 April it was reported that the forty prisons of Paris contained 6,921 prisoners; by 11 June this number had increased to 7,321 and by 28 July to 7,800. [4]

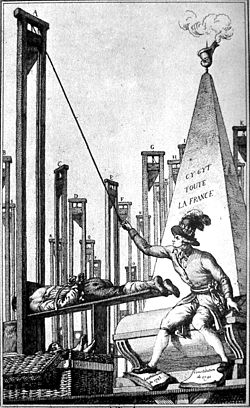

No Revolutionary Tribunal could work fast enough to prevent the ship of state sinking under such a sea of crime. What was to be done? Precedents had been created at Lyon, Marseille and elsewhere.... at Orange in particular, there had been set up, by decree of the Convention, a Commission of Five, which, by dispensing with the usual formalities of counsel and witness, had succeeded in condemning to death, within two months, 332 out of the 591 persons brought before it. [4]

The law was also prompted by the idea that members of the Convention who had supported Georges Danton were politically unreliable - a view shared by Robespierre, Couthon, Saint-Just and others. They felt that these people needed to be brought swiftly to justice without a full debate by the Convention itself. They considered Jean-Pierre-André Amar, for example, to be suspect. [5]

Consequences

The proposals were met with dismay when they were presented to the Convention. The Committee of Public Safety had not reviewed the text before it was presented, although it was presented in the name of the Committee itself. The Committee of General Security had not even been informed that the law was being drafted. [12]

Some of the deputies were uneasy, in particular, about the removal of their immunity and asked for the debate to be adjourned so the clauses could be examined. Robespierre refused and demanded immediate discussion. At his insistence the entire decree was voted on, clause by clause. It passed. [5] The next day, 11 June, when Robespierre was absent, Bourdon de l'Oise and Merlin de Douai put forward an amendment proclaiming the inalienable right of the Convention to impeach its own members. The amendment was passed. [5]

Furious, Robespierre and Couthon returned to the Convention the next day, 12 June, and demanded that the amendment of the previous day be revoked. Robespierre made a number of veiled threats and during the debate clashed particularly with Jean-Lambert Tallien. [13] The Convention acceded to Robespierre's wishes and restored the original text of the decree Couthon had drafted. [5]

As the Terror accelerated and members felt more and more threatened, Tallien and others began to make plans for the overthrow of Robespierre. Less than two months later, on 27 July, Tallien and his associates overthrew Robespierre, beginning the Thermidorian Reaction.

The Law of 22 Prairial was repealed on 1 August 1794 and Antoine Quentin Fouquier-Tinville, who had presided over the Revolutionary Tribunal, was arrested and later guillotined. [14]

This page is based on this

Wikipedia article Text is available under the

CC BY-SA 4.0 license; additional terms may apply.

Images, videos and audio are available under their respective licenses.