Related Research Articles

Friedrich August von Hayek, often referred to by his initials F. A. Hayek, was an Austrian-British polymath, whose areas of interest included economics, political philosophy, psychology, and intellectual history. Hayek shared the 1974 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences with Gunnar Myrdal for work on money and economic fluctuations, and the interdependence of economic, social and institutional phenomena. His account of how prices communicate information is widely regarded as an important contribution to economics that led to him receiving the prize.

Keynesian economics are the various macroeconomic theories and models of how aggregate demand strongly influences economic output and inflation. In the Keynesian view, aggregate demand does not necessarily equal the productive capacity of the economy. It is influenced by a host of factors that sometimes behave erratically and impact production, employment, and inflation.

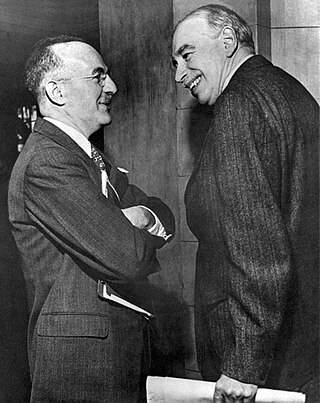

John Maynard Keynes, 1st Baron Keynes,, was an English economist and philosopher whose ideas fundamentally changed the theory and practice of macroeconomics and the economic policies of governments. Originally trained in mathematics, he built on and greatly refined earlier work on the causes of business cycles. One of the most influential economists of the 20th century, he produced writings that are the basis for the school of thought known as Keynesian economics, and its various offshoots. His ideas, reformulated as New Keynesianism, are fundamental to mainstream macroeconomics. He is known as the "father of macroeconomics".

Piero Sraffa FBA was an influential Italian economist who served as lecturer of economics at the University of Cambridge. His book Production of Commodities by Means of Commodities is taken as founding the neo-Ricardian school of economics.

The Bretton Woods Conference, formally known as the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, was the gathering of 730 delegates from all 44 allied nations at the Mount Washington Hotel, in Bretton Woods, New Hampshire, United States, to regulate the international monetary and financial order after the conclusion of World War II.

Arthur Cecil Pigou was an English economist. As a teacher and builder of the School of Economics at the University of Cambridge, he trained and influenced many Cambridge economists who went on to take chairs of economics around the world. His work covered various fields of economics, particularly welfare economics, but also included business cycle theory, unemployment, public finance, index numbers, and measurement of national output. His reputation was affected adversely by influential economic writers who used his work as the basis on which to define their own opposing views. He reluctantly served on several public committees, including the Cunliffe Committee and the 1919 Royal Commission on income tax.

William Henry Beveridge, 1st Baron Beveridge, was a British economist and Liberal politician who was a progressive, social reformer, and eugenicist who played a central role in designing the British welfare state. His 1942 report Social Insurance and Allied Services served as the basis for the welfare state put in place by the Labour government elected in 1945.

Jacob Viner was a Canadian economist and is considered with Frank Knight and Henry Simons to be one of the "inspiring" mentors of the early Chicago school of economics in the 1930s: he was one of the leading figures of the Chicago faculty. Paul Samuelson named Viner as one of the several "American saints in economics" born after 1860. He was an important figure in the field of political economy.

Lionel Charles Robbins, Baron Robbins, was a British economist, and prominent member of the economics department at the London School of Economics (LSE). He is known for his leadership at LSE, his proposed definition of economics, and for his instrumental efforts in shifting Anglo-Saxon economics from its Marshallian direction. He is famous for the quote, "Humans want what they can't have."

Colin Grant Clark was a British and Australian economist and statistician who worked in both the United Kingdom and Australia. He pioneered the use of gross national product (GNP) as the basis for studying national economies.

Abraham "Abba" Ptachya Lerner was a Russian-born American-British economist.

Events from the year 1931 in the United Kingdom.

Following the global 2007–2008 financial crisis, there was a worldwide resurgence of interest in Keynesian economics among prominent economists and policy makers. This included discussions and implementation of economic policies in accordance with the recommendations made by John Maynard Keynes in response to the Great Depression of the 1930s, most especially fiscal stimulus and expansionary monetary policy.

The Keynesian Revolution was a fundamental reworking of economic theory concerning the factors determining employment levels in the overall economy. The revolution was set against the then orthodox economic framework, namely neoclassical economics.

The post-war displacement of Keynesianism was a series of events which from mostly unobserved beginnings in the late 1940s, had by the early 1980s led to the replacement of Keynesian economics as the leading theoretical influence on economic life in the developed world. Similarly, the allied discipline known as development economics was largely displaced as the guiding influence on economic policies adopted by developing nations.

Anthony Philip Thirlwall was a British economist who was Professor of Applied Economics at the University of Kent. He made major contributions to regional economics; the analysis of unemployment and inflation; balance of payments theory, and to growth and development economics with particular reference to developing countries. He was the author of the bestselling textbook Economics of Development: Theory and Evidence now in its ninth edition. He was also the biographer and literary executor of the famous Cambridge economist Nicholas Kaldor. Perhaps his most notable contribution was to show that if long-run balance of payments equilibrium is a requirement for a country, its growth of national income can be approximated by the ratio of the growth of exports to the income elasticity of demand for imports.

Edward Frank Wise CB was a British economist, civil servant and Labour Party politician. He served as a Member of Parliament (MP) from 1929 to 1931.

Henry Higgs was a British civil servant, economist, and historian of economic thought.

Tyler Beck Goodspeed is an American economist and economic historian who was the acting chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers from June 2020 to January 2021. He resigned from his position on January 7 in the wake of the 2021 storming of the United States Capitol.

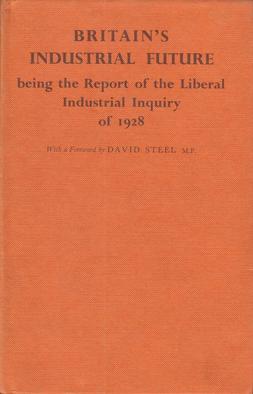

Britain's Industrial Future, commonly known as the Yellow Book, was the report of the British Liberal Party's Industrial Inquiry of 1928.

References

- 1 2 3 J. C. Stamp, The Report of the Macmillan Committee, The Economic Journal , pp. 424–435, Vol. 41, No. 163, September 1931.

- 1 2 3 Charles Loch Mowat, Britain Between the Wars: 1918-1940, pp. 260–261, Taylor & Francis, 1978, ISBN 0-416-29510-X.

- ↑ Donald Edward Moggridge, Maynard Keynes: An Economist's Biography, p. 510, Routledge, 1992, ISBN 0-415-05141-X.

- ↑ The Penguin Dictionary of Economics George Bannock, R. E. Baxter and Evan Davis. 5th Edition. Penguin Books 1992.

- 1 2 Friedrich A. von Hayek, The Road to Serfdom , pp. 66–67, University of Chicago Press, 1944.

- ↑ Philip Williamson, National Crisis and National Government, pp. 255–258, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 0-521-52141-6.

- 1 2 Chris Wrigley, A Companion to Early Twentieth-Century Britain, pp. 250-251, Wiley-Blackwell, 2003, ISBN 0-631-21790-8.

- 1 2 W. A. Thomas, The Finance of British Industry 1918–1976, pp. 117–118, Taylor & Francis, 2006, ISBN 0-415-37862-1.

- 1 2 Raymond Frost, The Macmillan Gap 1931-53, Oxford Economic Papers, Oxford University Press, p. 1.

- ↑ M. M. Postan, An Economic History of Western Europe: 1945-1964, p. 122, Taylor & Francis, 2006, ISBN 0-415-37921-0.