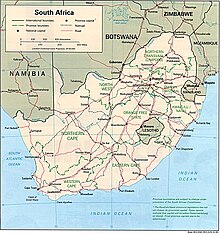

The Republic of South Africa is a unitary parliamentary democratic republic. The President of South Africa serves both as head of state and as head of government. The President is elected by the National Assembly and must retain the confidence of the Assembly in order to remain in office. South Africans also elect provincial legislatures which govern each of the country's nine provinces.

A Bantustan was a territory that the National Party administration of South Africa set aside for black inhabitants of South Africa and South West Africa, as a part of its policy of apartheid.

The Inkatha Freedom Party is a conservative political party in South Africa, which is a part of the current South African government of national unity together with the African National Congress (ANC). Although registered as a national party, it has had only minor electoral success outside its home province of KwaZulu-Natal. Mangosuthu Buthelezi, who served as chief minister of KwaZulu during the Apartheid period, founded the party in 1975 and led it until 2019. He was succeeded as party president in 2019 by Velenkosini Hlabisa.

Balthazar Johannes "B. J." Vorster, better known as John Vorster, was a South African politician who served as the prime minister of South Africa from 1966 to 1978 and the fourth state president of South Africa from 1978 to 1979. Known as B. J. Vorster during much of his career, he came to prefer the anglicized name John in the 1970s.

The United Party was a political party in South Africa. It was the country's ruling political party between 1934 and 1948.

Prince Mangosuthu Gatsha Buthelezi was a South African politician and Zulu prince who served as the traditional prime minister to the Zulu royal family from 1954 until his death in 2023. He was appointed to this post by King Bhekuzulu, the son of King Solomon kaDinuzulu, a brother to Buthelezi's mother Princess Magogo kaDinuzulu.

Goodwill Zwelithini kaBhekuzulu was the King of the Zulu nation from 1968 to his death in 2021.

Liberalism in South Africa has encompassed various traditions and parties.

KwaZulu was a semi-independent bantustan in South Africa, intended by the apartheid government as a homeland for the Zulu people. The capital was moved from Nongoma to Ulundi in 1980.

1994 in South Africa saw the transition from South Africa's National Party government who had ruled the country since 1948 and had advocated the apartheid system for most of its history, to the African National Congress (ANC) who had been outlawed in South Africa since the 1950s for its opposition to apartheid. The ANC won a majority in the first multiracial election held under universal suffrage. Previously, only white people were allowed to vote. There were some incidents of violence in the Bantustans leading up to the elections as some leaders of the Bantusans opposed participation in the elections, while other citizens wanted to vote and become part of South Africa. There were also bombings aimed at both the African National Congress and the National Party and politically-motivated murders of leaders of the opposing ANC and Inkatha Freedom Party (IFP).

The following lists events that happened during 1974 in South Africa.

The apartheid system in South Africa was ended through a series of bilateral and multi-party negotiations between 1990 and 1993. The negotiations culminated in the passage of a new interim Constitution in 1993, a precursor to the Constitution of 1996; and in South Africa's first non-racial elections in 1994, won by the African National Congress (ANC) liberation movement.

The South African Indian Congress (SAIC) was an umbrella body founded in 1921 to coordinate between political organisations representing Indians in the various provinces of South Africa. Its members were the Natal Indian Congress (NIC), the Transvaal Indian Congress (TIC), and, initially, the Cape British Indian Council. It advocated non-violent resistance to discriminatory laws and in its formative years was strongly influenced by the NIC's founder, Mahatma Gandhi.

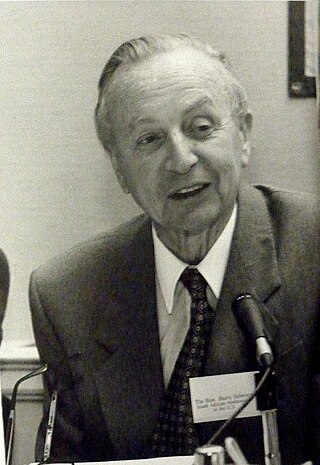

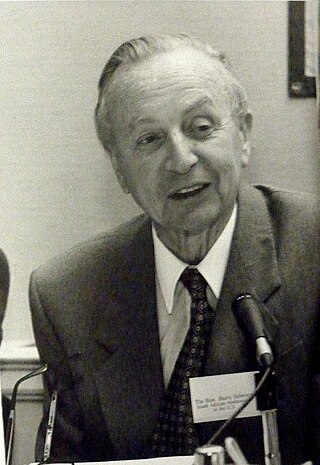

Harry Heinz Schwarz was a South African lawyer, statesman, and long-time political opposition leader against apartheid in South Africa who eventually served as the South African Ambassador to the United States during the country's transition to majority rule.

The Reform Party was an anti-apartheid political party that existed for just five months in 1975 and is one of the predecessor parties to the Democratic Alliance. The Reform Party was created on 11 February by a group of four Members of Parliament (MPs) who left the United Party under the guidance of the leader of the United Party in the Transvaal, Harry Schwarz, who became the party's leader. Schwarz and others were staunchly opposed to apartheid and called for a much more rigorous opposition to the National Party. They said that they no longer felt the UP was "the vehicle in which we can travel the path of verligtheid". The party had four MPs, two senators, ten members of the Transvaal Provincial Council, 14 out of the 36 Johannesburg City Councillors and four Randburg City Councillors. This made it the official opposition in the Transvaal Provincial Council.

Although the Democratic Alliance of South Africa in its present form is fairly new, its roots can be traced far back in South African political history, through a complex sequence of splits and mergers.

Mario Gaspare R. Oriani-Ambrosini was an Italian constitutional lawyer and politician who was a Member of Parliament in South Africa with the Inkatha Freedom Party.

Boervolk Radio presented by the Transvaal Separatists, is an internet-only radio station based in Kempton Park, South Africa.

Walter Sidney Felgate was a South African politician, businessman, and anthropologist. He served in the National Assembly from 1994 to 1997 and then in the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Legislature from 1998 until his retirement in 2003.