This article concerns the period 329 BC – 320 BC.

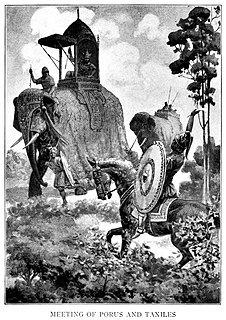

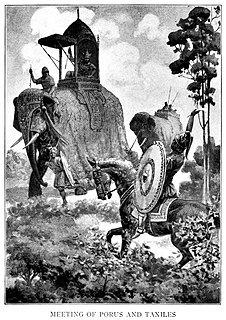

Porus or Poros, was an ancient Indian king whose territory spanned the region between the Hydaspes and Acesines, in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent. He is credited to have been a legendary warrior with exceptional skills. Porus fought against Alexander the Great in the Battle of the Hydaspes, thought to be fought at the site of modern-day Mong, Punjab, which is now part of the modern country of Pakistan. Though not recorded in any available ancient Indian source, Ancient Greek historians describe the battle and the aftermath of Alexander's victory. After the defeat and arrest of Porus in the war, Alexander asked Porus how he would like to be treated. Porus, although defeated, being a valiant, proud king, stated that he be treated like how Alexander himself would expect to be treated. Alexander was reportedly so impressed by his adversary that he not only reinstated him as a satrap of his own kingdom but also granted him dominion over lands to the south-east extending until the Hyphasis (Beas). Porus reportedly died sometime between 321 and 315 BC.

Seleucus I Nicator was one of the Diadochi. Having previously served as an infantry general under Alexander the Great, he eventually assumed the title of basileus and established the Seleucid Empire over much of the territory in the Near East which Alexander had conquered.

Hephaestion, son of Amyntor, was an ancient Macedonian nobleman and a general in the army of Alexander the Great. He was "by far the dearest of all the king's friends; he had been brought up with Alexander and shared all his secrets." This relationship lasted throughout their lives, and was compared, by others as well as themselves, to that of Achilles and Patroclus.

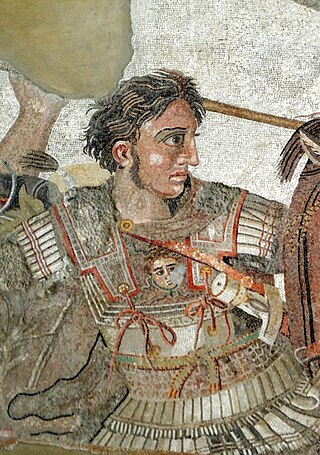

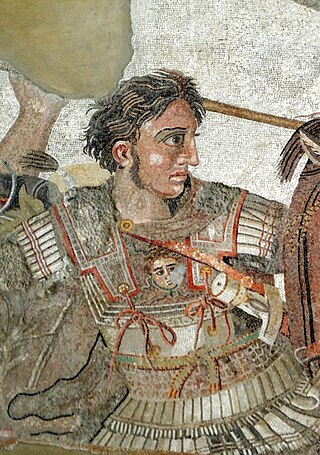

The Battle of Issus occurred in southern Anatolia, on November 5, 333 BC between the Hellenic League led by Alexander the Great and the Achaemenid Empire, led by Darius III, in the second great battle of Alexander's conquest of Asia. The invading Macedonian troops defeated Persia. After the Hellenic League soundly defeated the Persian satraps of Asia Minor at the Battle of the Granicus, Darius took personal command of his army. He gathered reinforcements and led his men in a surprise march behind the Hellenic advance to cut their line of supply. This forced Alexander to countermarch, setting the stage for the battle near the mouth of the Pinarus River and the town of Issus.

The Battle of Gaugamela, also called the Battle of Arbela, was the decisive battle of Alexander the Great's invasion of the Persian Achaemenid Empire. In 331 BC Alexander's army of the Hellenic League met the Persian army of Darius III near Gaugamela, close to the modern city of Dohuk in Iraqi Kurdistan. Though heavily outnumbered, Alexander emerged victorious due to his army's superior tactics and his deft employment of light infantry. It was a decisive victory for the Hellenic League and led to the fall of the Achaemenid Empire.

The wars of Alexander the Great were fought by King Alexander III of Macedon, first against the Achaemenid Persian Empire under Darius III, and then against local chieftains and warlords as far east as Punjab, India. Due to the sheer scale of these wars, and the fact that Alexander was generally undefeated in battle, he has been regarded as one of the most successful military commanders of all time. By the time of his death, he had conquered most of the world known to the ancient Greeks. Although being successful as a military commander, he failed to provide any stable alternative to the Achaemenid Empire—his untimely death threw the vast territories he conquered into civil war.

Meleager was a Macedonian officer who served Alexander the Great with distinction. Among the king's generals who went with him to Asia, he was the most experienced as the only military figure who exceeded his experience was the Macedonian general Antipater who remained in Macedon during Alexander's entire Asian campaign.

The pezhetairoi were the backbone of the Macedonian army and Diadochi kingdoms. They were literally "foot companions".

Taxiles was the Greek chroniclers' name for a prince or king who reigned over the tract between the Indus and the Jhelum (Hydaspes) Rivers in the Punjab region of the Indian subcontinent at the time of Alexander the Great's expedition. His local name was Ambhi, and the Greeks appear to have called him Taxiles or Taxilas, from the name of his capital city of Taxila, near the modern city of Attock, Pakistan.

Philip, son of Machatas and brother of Harpalus, was an officer in the service of Alexander the Great, who in 327 BC was appointed by Alexander as satrap of India, including the provinces westward of the Hydaspes, as far south as the junction of the Indus with the Acesines. After the conquest of the Malli and Oxydracae, these tribes also were added to his government.

Philotas was a Macedonian officer in the service of Alexander the Great, who commanded one taxis or division of the phalanx during the advance into Sogdiana and India. It seems probable that he is the same person mentioned by Curtius, as one of those rewarded by the king at Babylon for their distinguished services. There is little doubt also, that he is the same to whom the government of Cilicia was assigned in the distribution of the provinces after the death of Alexander, 323 BC. In 321 BC, he was deprived of his government by Perdiccas and replaced by Philoxenus, but it would seem that this was only in order to employ him elsewhere, as we find him still closely attached to the party of Perdiccas, and after the death of the regent united with Alcetas, Attalus, and their partisans, in the contest against Antigonus. He was taken prisoner, together with Attalus, Docimus, and Polemon, in 320 BC, and shared with them their imprisonment, as well as the daring enterprise by which they for a time recovered their liberty, when they took possession of their prison, overpowering their guards. He again fell into the power of Antigonus, in 316 BC.

Neoptolemus was a Macedonian officer who served under Alexander the Great.

Peithon, son of Agenor was an officer in the expedition of Alexander the Great to India, who became satrap of the Indus from 325 to 316 BCE, and then satrap of Babylon, from 316 to 312 BCE, until he died at the Battle of Gaza in 312 BCE.

The Partition of Babylon was the first of the conferences and ensuing agreements that divided the territories of Alexander the Great. It was held at Babylon in June 323 BC. Alexander’s death at the age of 32 had left an empire that stretched from Greece all the way to India. The issue of succession resulted from the claims of the various supporters of Philip Arrhidaeus, and the as-of-then unborn child of Alexander and Roxana, among others. The settlement saw Arrhidaeus and Alexander’s child designated as joint kings with Perdiccas serving as regent. The territories of the empire became satrapies divided between the senior officers of the Macedonian army and some local governors and rulers. The partition was solidified at the further agreements at Triparadisus and Persepolis over the following years and began the series of conflicts that comprise the Wars of the Diadochi.

The Battle of the Persian Gate was a military conflict between Achaemenid Persian army, commanded by the satrap of Persis, Ariobarzanes, and the invading Hellenic League, commanded by Alexander the Great. In the winter of 330 BC, Ariobarzanes led a last stand of the outnumbered Persian forces at the Persian Gates near Persepolis, holding the Macedonian army for a month. Alexander eventually found a path to the rear of the Persians from the captured prisoners of war or a local shepherd, eventually capturing Persepolis.

The Indian campaign of Alexander the Great began in 326 BC. After conquering the Achaemenid Empire of Persia, the Macedonian king, Alexander, launched a campaign into the Indian subcontinent in present-day Pakistan, part of which formed the easternmost territories of the Achaememid Empire following the Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley. The rationale for this campaign is usually said to be Alexander's desire to conquer the entire known world, which the Greeks thought ended in India.

The Cophen Campaign was conducted by Alexander the Great between May 327 BC and March 326 BC. It was conducted in Swat in what is now the Punjab region in Pakistan. Alexander's goal was to secure his line of communications so that he could conduct a campaign in India proper. To achieve this, he needed to capture a number of fortresses controlled by the local tribes.