Glia, also called glial cells (gliocytes) or neuroglia, are non-neuronal cells in the central nervous system and the peripheral nervous system that do not produce electrical impulses. The neuroglia make up more than one half the volume of neural tissue in our body. They maintain homeostasis, form myelin in the peripheral nervous system, and provide support and protection for neurons. In the central nervous system, glial cells include oligodendrocytes, astrocytes, ependymal cells and microglia, and in the peripheral nervous system they include Schwann cells and satellite cells.

Neurotoxicity is a form of toxicity in which a biological, chemical, or physical agent produces an adverse effect on the structure or function of the central and/or peripheral nervous system. It occurs when exposure to a substance – specifically, a neurotoxin or neurotoxicant– alters the normal activity of the nervous system in such a way as to cause permanent or reversible damage to nervous tissue. This can eventually disrupt or even kill neurons, which are cells that transmit and process signals in the brain and other parts of the nervous system. Neurotoxicity can result from organ transplants, radiation treatment, certain drug therapies, recreational drug use, exposure to heavy metals, bites from certain species of venomous snakes, pesticides, certain industrial cleaning solvents, fuels and certain naturally occurring substances. Symptoms may appear immediately after exposure or be delayed. They may include limb weakness or numbness, loss of memory, vision, and/or intellect, uncontrollable obsessive and/or compulsive behaviors, delusions, headache, cognitive and behavioral problems and sexual dysfunction. Chronic mold exposure in homes can lead to neurotoxicity which may not appear for months to years of exposure. All symptoms listed above are consistent with mold mycotoxin accumulation.

Astrogliosis is an abnormal increase in the number of astrocytes due to the destruction of nearby neurons from central nervous system (CNS) trauma, infection, ischemia, stroke, autoimmune responses or neurodegenerative disease. In healthy neural tissue, astrocytes play critical roles in energy provision, regulation of blood flow, homeostasis of extracellular fluid, homeostasis of ions and transmitters, regulation of synapse function and synaptic remodeling. Astrogliosis changes the molecular expression and morphology of astrocytes, in response to infection for example, in severe cases causing glial scar formation that may inhibit axon regeneration.

Microglia are a type of neuroglia located throughout the brain and spinal cord. Microglia account for about 10-15% of cells found within the brain. As the resident macrophage cells, they act as the first and main form of active immune defense in the central nervous system (CNS). Microglia originate in the yolk sac under a tightly regulated molecular process. These cells are distributed in large non-overlapping regions throughout the CNS. Microglia are key cells in overall brain maintenance—they are constantly scavenging the CNS for plaques, damaged or unnecessary neurons and synapses, and infectious agents. Since these processes must be efficient to prevent potentially fatal damage, microglia are extremely sensitive to even small pathological changes in the CNS. This sensitivity is achieved in part by the presence of unique potassium channels that respond to even small changes in extracellular potassium. Recent evidence shows that microglia are also key players in the sustainment of normal brain functions under healthy conditions. Microglia also constantly monitor neuronal functions through direct somatic contacts and exert neuroprotective effects when needed.

Neuroprotection refers to the relative preservation of neuronal structure and/or function. In the case of an ongoing insult the relative preservation of neuronal integrity implies a reduction in the rate of neuronal loss over time, which can be expressed as a differential equation. It is a widely explored treatment option for many central nervous system (CNS) disorders including neurodegenerative diseases, stroke, traumatic brain injury, spinal cord injury, and acute management of neurotoxin consumption. Neuroprotection aims to prevent or slow disease progression and secondary injuries by halting or at least slowing the loss of neurons. Despite differences in symptoms or injuries associated with CNS disorders, many of the mechanisms behind neurodegeneration are the same. Common mechanisms of neuronal injury include decreased delivery of oxygen and glucose to the brain, energy failure, increased levels in oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, excitotoxicity, inflammatory changes, iron accumulation, and protein aggregation. Of these mechanisms, neuroprotective treatments often target oxidative stress and excitotoxicity—both of which are highly associated with CNS disorders. Not only can oxidative stress and excitotoxicity trigger neuron cell death but when combined they have synergistic effects that cause even more degradation than on their own. Thus limiting excitotoxicity and oxidative stress is a very important aspect of neuroprotection. Common neuroprotective treatments are glutamate antagonists and antioxidants, which aim to limit excitotoxicity and oxidative stress respectively.

The neuroimmune system is a system of structures and processes involving the biochemical and electrophysiological interactions between the nervous system and immune system which protect neurons from pathogens. It serves to protect neurons against disease by maintaining selectively permeable barriers, mediating neuroinflammation and wound healing in damaged neurons, and mobilizing host defenses against pathogens.

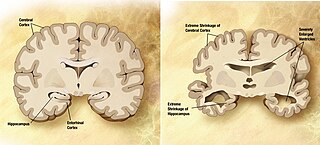

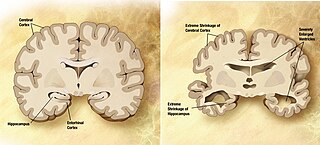

A neurodegenerative disease is caused by the progressive loss of structure or function of neurons, in the process known as neurodegeneration. Such neuronal damage may ultimately involve cell death. Neurodegenerative diseases include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson's disease, Alzheimer's disease, Huntington's disease, multiple system atrophy, tauopathies, and prion diseases. Neurodegeneration can be found in the brain at many different levels of neuronal circuitry, ranging from molecular to systemic. Because there is no known way to reverse the progressive degeneration of neurons, these diseases are considered to be incurable; however research has shown that the two major contributing factors to neurodegeneration are oxidative stress and inflammation. Biomedical research has revealed many similarities between these diseases at the subcellular level, including atypical protein assemblies and induced cell death. These similarities suggest that therapeutic advances against one neurodegenerative disease might ameliorate other diseases as well.

Gliosis is a nonspecific reactive change of glial cells in response to damage to the central nervous system (CNS). In most cases, gliosis involves the proliferation or hypertrophy of several different types of glial cells, including astrocytes, microglia, and oligodendrocytes. In its most extreme form, the proliferation associated with gliosis leads to the formation of a glial scar.

Neurturin (NRTN) is a protein that is encoded in humans by the NRTN gene. Neurturin belongs to the glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) family of neurotrophic factors, which regulate the survival and function of neurons. Neurturin’s role as a growth factor places it in the transforming growth factor beta (TGF-beta) subfamily along with its homologs persephin, artemin, and GDNF. It shares a 42% similarity in amino acid sequence with mature GDNF. It is also considered a trophic factor and critical in the development and growth of neurons in the brain. Neurotrophic factors like neurturin have been tested in several clinical trial settings for the potential treatment of neurodegenerative diseases, specifically Parkinson's disease.

CX3C motif chemokine receptor 1 (CX3CR1), also known as the fractalkine receptor or G-protein coupled receptor 13 (GPR13), is a transmembrane protein of the G protein-coupled receptor 1 (GPCR1) family and the only known member of the CX3C chemokine receptor subfamily.

Hydroxycarboxylic acid receptor 2 (HCA2), also known as GPR109A and niacin receptor 1 (NIACR1), is a protein which in humans is encoded (its formation is directed) by the HCAR2 gene and in rodents by the Hcar2 gene. The human HCAR2 gene is located on the long (i.e., "q") arm of chromosome 12 at position 24.31 (notated as 12q24.31). Like the two other hydroxycarboxylic acid receptors, HCA1 and HCA3, HCA2 is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) located on the surface membrane of cells. HCA2 binds and thereby is activated by D-β-hydroxybutyric acid (hereafter termed β-hydroxybutyric acid), butyric acid, and niacin (also known as nicotinic acid). β-Hydroxybutyric and butyric acids are regarded as the endogenous agents that activate HCA2. Under normal conditions, niacin's blood levels are too low to do so: it is given as a drug in high doses in order to reach levels that activate HCA2.

Colony stimulating factor 1 receptor (CSF1R), also known as macrophage colony-stimulating factor receptor (M-CSFR), and CD115, is a cell-surface protein encoded by the human CSF1R gene. CSF1R is a receptor that can be activated by two ligands: colony stimulating factor 1 (CSF-1) and interleukin-34 (IL-34). CSF1R is highly expressed in myeloid cells, and CSF1R signaling is necessary for the survival, proliferation, and differentiation of many myeloid cell types in vivo and in vitro. CSF1R signaling is involved in many diseases and is targeted in therapies for cancer, neurodegeneration, and inflammatory bone diseases.

Receptor-interacting serine/threonine-protein kinase 1 (RIPK1) functions in a variety of cellular pathways related to both cell survival and death. In terms of cell death, RIPK1 plays a role in apoptosis and necroptosis. Some of the cell survival pathways RIPK1 participates in include NF-κB, Akt, and JNK.

Triggering receptor expressed on myeloid cells 2(TREM2) is a protein that in humans is encoded by the TREM2 gene. TREM2 is expressed on macrophages, immature monocyte-derived dendritic cells, osteoclasts, and microglia, which are immune cells in the central nervous system. In the liver, TREM2 is expressed by several cell types, including macrophages, that respond to injury. In the intestine, TREM2 is expressed by myeloid-derived dendritic cells and macrophage. TREM2 is overexpressed in many tumor types and has anti-inflammatory activities. It might therefore be a good therapeutic target.

Quinolinic acid, also known as pyridine-2,3-dicarboxylic acid, is a dicarboxylic acid with a pyridine backbone. It is a colorless solid. It is the biosynthetic precursor to niacin.

Neuroinflammation is inflammation of the nervous tissue. It may be initiated in response to a variety of cues, including infection, traumatic brain injury, toxic metabolites, or autoimmunity. In the central nervous system (CNS), including the brain and spinal cord, microglia are the resident innate immune cells that are activated in response to these cues. The CNS is typically an immunologically privileged site because peripheral immune cells are generally blocked by the blood–brain barrier (BBB), a specialized structure composed of astrocytes and endothelial cells. However, circulating peripheral immune cells may surpass a compromised BBB and encounter neurons and glial cells expressing major histocompatibility complex molecules, perpetuating the immune response. Although the response is initiated to protect the central nervous system from the infectious agent, the effect may be toxic and widespread inflammation as well as further migration of leukocytes through the blood–brain barrier may occur.

The pathophysiology of Parkinson's disease is death of dopaminergic neurons as a result of changes in biological activity in the brain with respect to Parkinson's disease (PD). There are several proposed mechanisms for neuronal death in PD; however, not all of them are well understood. Five proposed major mechanisms for neuronal death in Parkinson's Disease include protein aggregation in Lewy bodies, disruption of autophagy, changes in cell metabolism or mitochondrial function, neuroinflammation, and blood–brain barrier (BBB) breakdown resulting in vascular leakiness.

Microglia are the primary immune cells of the central nervous system, similar to peripheral macrophages. They respond to pathogens and injury by changing morphology and migrating to the site of infection/injury, where they destroy pathogens and remove damaged cells.

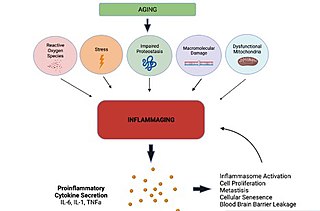

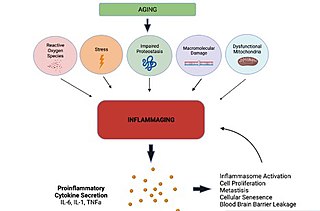

Inflammaging is a chronic, sterile, low-grade inflammation that develops with advanced age, in the absence of overt infection, and may contribute to clinical manifestations of other age-related pathologies. Inflammaging is thought to be caused by a loss of control over systemic inflammation resulting in chronic overstimulation of the innate immune system. Inflammaging is a significant risk factor in mortality and morbidity in aged individuals.

Katerina Akassoglou is a neuroimmunologist who is a Senior Investigator and Director of In Vivo Imaging Research at the Gladstone Institutes. Akassoglou holds faculty positions as a Professor of Neurology at the University of California, San Francisco. Akassoglou has pioneered investigations of blood-brain barrier integrity and development of neurological diseases. She found that compromised blood-brain barrier integrity leads to fibrinogen leakage into the brain inducing neurodegeneration. Akassoglou is internationally recognized for her scientific discoveries.