In diarrhea

When diarrhea occurs, hydration should increase to prevent dehydration.

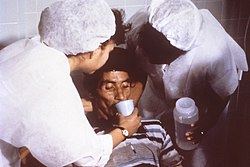

The WHO recommends using the oral rehydration solution (ORS) if available, but homemade solutions such as salted rice water, salted yogurt drinks, vegetable and chicken soups with salt can also be given. The goal is to provide both water and salt: drinks can be mixed with half a teaspoon to full teaspoon of salt (from one-and-a-half to three grams) added per liter. Clean plain water can also be one of several fluids given. [1]

ORS is mass-produced as commercial solutions such as Pedialyte, and relief agencies such as UNICEF widely distribute packets of pre-mixed salts and sugar. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes a homemade ORS with one liter water with one teaspoon salt (or 3 grams) and six teaspoons sugar (or 18 grams) added [1] (approximately the "taste of tears"). [3] However, the WHO does not generally recommend homemade solutions as how to make them is easily forgotten. [1] Rehydration Project recommends adding the same amount of sugar but only one-half a teaspoon of salt, stating that this more dilute approach is less risky with very little loss of effectiveness. [4] Both agree that drinks with too much sugar or salt can make dehydration worse. [1] [4]

Medium dehydration

In what the World Health Organization (WHO) terms "some dehydration," the child or adult is restless and irritable, is thirsty, and will drink eagerly. [1]

WHO recommends that if there is vomiting, don't stop, but do pause for 5–10 minutes and then restart at a slower pace. (Vomiting seldom prevents successful rehydration since most of the fluid is still absorbed. Plus, vomiting usually stops after the first one to four hours of rehydration.) With the older WHO solution, also give some clean water during rehydration. With the newer reduced-osmolarity, more dilute solution, this is not necessary. [1]

Begin to offer food after the initial four-hour rehydration period with children and adults. With infants, continue to breastfeed even during rehydration as long as the infant will breastfeed. Begin zinc supplementation after initial four-hour rehydration to reduce severity and duration of episode. If available, zinc supplementation should be continued for 10 to 14 days. During the initial period of rehydration, the patient should be re-assessed at least every four hours. [1]

The family should be provided with at least two days worth of ORS packets. WHO recommends, in addition to infants continued to be breastfed, that children older than six months be given some food before being sent home, which helps to emphasize to parents the importance of continuing to feed the child during diarrhea. [1]

Severe dehydration

In severe dehydration, the person may be lethargic or unconscious, drinks poorly, or may not be able to drink. [1]

In malnourished persons, rehydration should be performed relatively slowly by drinking or by nasogastric tube unless the person is also experiencing shock, in which case it should be performed quicker. Malnourished patients should receive a modified ORS which has less sodium, more potassium, and modestly more sugar. For patients not malnourished, rehydration should be performed relatively rapidly by means of intravenous (IV) solution. For infants under one year of age, WHO recommends giving, within the first hour, 30 milliliters of Ringer's Lactate Solution for each kilogram of body weight, and then, within the next five hours, 70 milliliters of Ringer's Lactate per kilogram of body weight. For children over one year and for adults, WHO recommends, within the first half hour, 30 milliliters of Ringer's Lactate per kilogram of body weight, and then, within the next two-and-a-half hours, 70 milliliters per kilogram. For example, if a child weighs fifteen kilograms (who is obviously over one year of age), he or she should receive 450 ml of Ringer's Lactate Solution within the first half hour, and then 1,050 ml of Ringer's Lactate within the next two-and-a-half hours. Patients who can drink, even poorly, should be given Oral Rehydration Solution (ORS) by mouth until the IV drip is running. In addition, all patients should start to receive some ORS when they are able to drink without difficulty, which is usually three to four hours for infants and one to two hours for older persons. ORS provides additional base and potassium which may not be adequately supplied by IV fluid. Ideally, patients should be reassessed every fifteen to thirty minutes until a strong radial pulse is present, and thereafter, assessed at least hourly to confirm that hydration is improving. Hopefully, patients will graduate to the medium dehydration or "some" dehydration category and receive continued treatment as above. [1]

Inadequate replacement of potassium losses during diarrhea can lead to potassium depletion and hypokalaemia (low serum potassium) especially in children with malnutrition. This can potentially cause muscle weakness, impaired kidney function, and cardiac arrhythmia. Hypokalaemia is worsened when base is given to treat acidosis without simultaneously providing potassium, as happens in standard IVs including Ringer's Lactate Solution. ORS can help correct potassium deficit, as can giving foods rich in potassium during diarrhea and after it has stopped. [1]

As in above sections, for all patients, supplemental zinc can help to reduce the severity and duration of diarrhea. In addition, supplemental vitamin A is often recommended, particular for children who have diarrhea during or shortly after measles, or in children who are already malnourished, although ideally for all patients. [1]

In children

WHO recommends a child with diarrhea continue to be fed. Continued feeding speeds the recovery of normal intestinal function. In contrast, children whose food is restricted, have diarrhea of longer duration and recover intestinal function more slowly. A child should also continue to be breastfed. [1] And in the example of the treatment of cholera, CDC also recommends that persons continue to eat and children continue to be breastfed. [2]

If IV treatment is not available at the facility, WHO recommends sending the child to a nearby facility if it can be reached within 30 minutes and providing the mother with ORS to administer to the child during the trip. If another facility is not available, ORS can be given by mouth as the child can drink and/or by nasogastric tube. [1]

WHO states that knowing the levels of serum electrolytes rarely changes the recommended treatment of children with diarrhea and dehydration, and furthermore, that these values are often misinterpreted. Most electrolyte imbalances are adequately treated by ORS. For example, a child who has been given an excess of sugar or salt like that which is in commercial soft drinks, sugared fruit drinks, or over-concentrated infant formula, may develop hypernatraemic dehydration. This occurs when these over-concentrated solutions sit in the gut and draw water from the rest of the body, and the reduced fluids in the body's tissues then have a higher proportion of salt to fluid. Children with serum sodium greater 150 mmol/liter have thirst out of proportion to other signs of dehydration. There is a danger of convulsions which usually occur when serum sodium concentrations are greater than 165 mmol/liter. Less commonly, convulsions can also occur when serum sodium is less than 130 mmol/liter. Treatment with ORS can usually bring serum sodium concentrations back to normal within twenty-four hours. [1]

Children with diarrhea who drink mostly water or overly dilute drinks with too little salt may develop hyponatraemia (serum sodium less than 130 mmol/liter). This is especially common in children with shigellosis and in severely malnourished children with edema. ORS is safe and effective for nearly all children with hyponatraemia, an exception being children with edema for whom ORS provides too much sodium. [1]