Related Research Articles

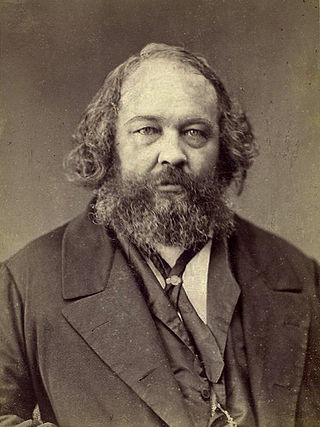

Mikhail Alexandrovich Bakunin was a Russian revolutionary anarchist. He is among the most influential figures of anarchism and a major figure in the revolutionary socialist, social anarchist, and collectivist anarchist traditions. Bakunin's prestige as a revolutionary also made him one of the most famous ideologues in Europe, gaining substantial influence among radicals throughout Russia and Europe.

Errico Malatesta was an Italian anarchist propagandist and revolutionary socialist. He edited several radical newspapers and spent much of his life exiled and imprisoned, having been jailed and expelled from Italy, Britain, France, and Switzerland. Originally a supporter of insurrectionary propaganda by deed, Malatesta later advocated for syndicalism. His exiles included five years in Europe and 12 years in Argentina. Malatesta participated in actions including an 1895 Spanish revolt and a Belgian general strike. He toured the United States, giving lectures and founding the influential anarchist journal La Questione Sociale. After World War I, he returned to Italy where his Umanità Nova had some popularity before its closure under the rise of Mussolini.

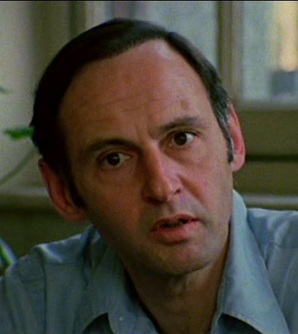

Grigorii Petrovich Maksimov was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist. From the first days of the Russian Revolution, he played a leading role in the country's syndicalist movement – editing the newspaper Golos Truda and organising the formation of factory committees. Following the October Revolution, he came into conflict with the Bolsheviks, who he fiercely criticised for their authoritarian and centralist tendencies. For his anti-Bolshevik activities, he was eventually arrested and imprisoned, before finally being deported from the country. In exile, he continued to lead the anarcho-syndicalist movement, spearheading the establishment of the International Workers' Association (IWA), of which he was a member until his death.

Anarchists have employed certain symbols for their cause, including most prominently the circle-A and the black flag. Anarchist cultural symbols have been prevalent in popular culture since around the turn of the 21st century, concurrent with the anti-globalization movement. The punk subculture has also had a close association with anarchist symbolism.

The history of anarchism is ambiguous, primarily due to the ambiguity of anarchism itself. Scholars find it hard to define or agree on what anarchism means, which makes outlining its history difficult. There is a range of views on anarchism and its history. Some feel anarchism is a distinct, well-defined 19th and 20th century movement while others identify anarchist traits long before first civilisations existed.

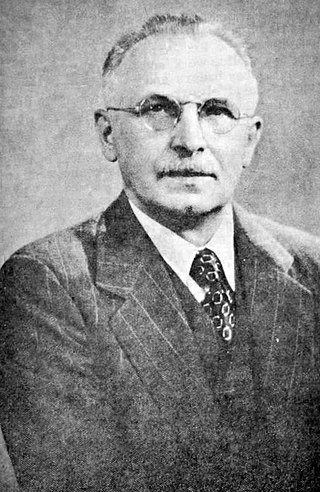

Paul Avrich was an American historian specialising in the 19th and early 20th century anarchist movement in Russia and the United States. He taught at Queens College, City University of New York, for his entire career, from 1961 to his retirement as distinguished professor of history in 1999. He wrote ten books, mostly about anarchism, including topics such as the 1886 Haymarket Riot, 1921 Sacco and Vanzetti case, 1921 Kronstadt naval base rebellion, and an oral history of the movement.

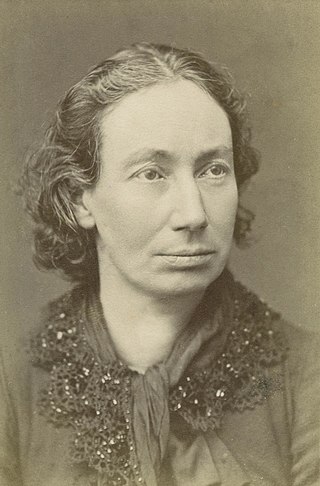

Louise Michel was a teacher and important figure in the Paris Commune. Following her penal transportation to New Caledonia she embraced anarchism. When returning to France she emerged as an important French anarchist and went on speaking tours across Europe. The journalist Brian Doherty has called her the "French grande dame of anarchy." Her use of a black flag at a demonstration in Paris in March 1883 was also the earliest known of what would become known as the anarchy black flag.

Varlam Nikolozi dze Cherkezishvili was a Georgian aristocrat and journalist involved in Georgian anarchist and national liberation movements.

Anarchism in France can trace its roots to thinker Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, who grew up during the Restoration and was the first self-described anarchist. French anarchists fought in the Spanish Civil War as volunteers in the International Brigades. According to journalist Brian Doherty, "The number of people who subscribed to the anarchist movement's many publications was in the tens of thousands in France alone."

Anarchism in Russia developed out of the populist and nihilist movements' dissatisfaction with the government reforms of the time.

God and the State is an unfinished manuscript by the Russian anarchist philosopher Mikhail Bakunin, published posthumously in 1882. The work criticises Christianity and the then-burgeoning technocracy movement from a materialist, anarchist and individualist perspective.

Francesco Saverio Merlino was an Italian lawyer, anarchist activist and theorist of libertarian socialism.

Alexander "Sanya" Moiseyevich Schapiro or Shapiro was a Russian anarcho-syndicalist activist. Born in southern Russia, Schapiro left Russia at an early age and spent most of his early activist years in London.

Émile Jean-Marie Gautier was a French anarchist and later a journalist. He coined the term "social Darwinism".

Collectivist anarchism, also called anarchist collectivism and anarcho-collectivism, is an anarchist school of thought that advocates the abolition of both the state and private ownership of the means of production. In their place, it envisions both the collective ownership of the means of production and the entitlement of workers to the fruits of their own labour, which would be ensured by a societal pact between individuals and collectives. Collectivists considered trade unions to be the means through which to bring about collectivism through a social revolution, where they would form the nucleus for a post-capitalist society.

The Haymarket Conspiracy: Transatlantic Anarchist Networks is a 2012 book by historian Timothy Messer-Kruse on the Haymarket affair and the origins of American anarchism.

Freie Arbeiter Stimme was a Yiddish-language anarchist newspaper published from New York City's Lower East Side between 1890 and 1977. It was among the world's longest running anarchist journals, and the primary organ of the Jewish anarchist movement in the United States; at the time that it ceased publication it was the world's oldest Yiddish newspaper. Historian of anarchism Paul Avrich described the paper as playing a vital role in Jewish–American labor history and upholding a high literary standard, having published the most lauded writers and poets in Yiddish radicalism. The paper's editors were major figures in the Jewish–American anarchist movement: David Edelstadt, Saul Yanovsky, Joseph Cohen, Hillel Solotaroff, Roman Lewis, and Moshe Katz.

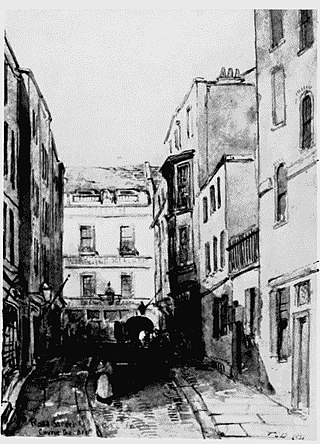

The Rose Street Club was a far-left, anarchist organisation based in what is now Manette Street, London. Originally centred around London's German community, and acting as a meeting point for new immigrants, it became one of the leading radical clubs of Victorian London in the late-nineteenth century. Although its roots went back to the 1840s, it was properly formed in 1877 by members of a German émigré workers' education group, which soon became frequented by London radicals, and within a few years had led to the formation of similar clubs, sometimes in support and sometimes in rivalry. The Rose Street Club provided a platform for the radical speakers and agitators of the day and produced its own paper, Freiheit—which was distributed over Europe, and especially Germany—and pamphlets for other groups and individuals. Although radical, the club initially focused as much on providing a social service to its members as on activism. With the arrival of the anarchist Johann Most in London in the early 1880s, and his increasing influence within the club, it became increasingly aligned with anarchism.

The International Social Revolutionary Congress was an anarchist meeting in London between 14 and 20 July 1881, with the aim of founding a new International organization for anti-authoritiarian socialism.

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Avrich 1984, p. 56.

- ↑ Social Anarchism 1990, p. 43.

- 1 2 3 Messer-Kruse 2012, p. 205.

- 1 2 Bantman 2006, p. 965.

- ↑ Young 2011.

- ↑ Messer-Kruse 2012, p. 141.

- ↑ Messer-Kruse 2012, p. 84.

- ↑ Shpayer 1981, p. 20.

- ↑ Lincoln 1977, p. 218.

- ↑ Quail 1978.

- ↑ Messer-Kruse 2012, p. 83.

- ↑ Avrich 1990, p. 278.

- ↑ On Picket Duty 1885, p. 47.

- ↑ An English anarchist 1885, p. 10.

Sources

- An English anarchist (1885). The Criminal law amendment act . Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Avrich, Paul (1984). The Haymarket Tragedy. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-00600-0 . Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Avrich, Paul (1990-02-01). Anarchist Portraits. Princeton University Press. p. 278. ISBN 978-0-691-00609-3 . Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Bantman, Constance (2006). "Internationalism without an International? Cross-Channel Anarchist Networks, 1880-1914". Revue belge de philologie et d'histoire. 84 (84–4): 961–981. doi:10.3406/rbph.2006.5056 . Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Lincoln, WE (1977). ""New Party" Radicalism and the Founding of the Democratic Federation 1881". Popular Radicalism and the Beginnings of the New Socialist Movement in Britain, 1870-1885 (PDF). Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Messer-Kruse, Timothy (2012-07-31). The Haymarket Conspiracy: Transatlantic Anarchist Networks. University of Illinois Press. ISBN 978-0-252-09414-9 . Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- "On Picket Duty". Liberty (Not the Daughter But the Mother of Order). 1885-04-11. p. 47. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Quail, John (1978). "The Anarchist and Freedom ... and Dan Chatterton". The Slow Burning Fuse. London: Paladin Books. Archived from the original on 2009-10-28. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Shpayer, Haia (June 1981). "British Anarchism 1881-1914: Reality and Appearance" (PDF). Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Social Anarchism. Atlantic Center for Research and Education. 1990. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- Young, Sarah J. (9 January 2011). "Russians in London: Pyotr Kropotkin" . Retrieved 2013-08-30.