In architecture, the frieze is the wide central section part of an entablature and may be plain in the Ionic or Doric order, or decorated with bas-reliefs. Paterae are also usually used to decorate friezes. Even when neither columns nor pilasters are expressed, on an astylar wall it lies upon the architrave and is capped by the moldings of the cornice. A frieze can be found on many Greek and Roman buildings, the Parthenon Frieze being the most famous, and perhaps the most elaborate. This style is typical for the Persians.

Sanchi is a Buddhist complex, famous for its Great Stupa, on a hilltop at Sanchi Town in Raisen District of the State of Madhya Pradesh, India. It is located, about 23 kilometers from Raisen town, district headquarter and 46 kilometres (29 mi) north-east of Bhopal, capital of Madhya Pradesh.

Indian architecture is rooted in the history, culture, and religion of India. Among several architectural styles and traditions, the best-known include the many varieties of Hindu temple architecture and Indo-Islamic architecture, especially Rajput architecture, Mughal architecture, South Indian architecture, and Indo-Saracenic architecture. Early Indian architecture was made from wood, which did not survive due to rotting and instability in the structures. Instead, the earliest existing architecture are made with Indian rock-cut architecture, including many Buddhist, Hindu, and Jain temples.

In architecture the capital or chapiter forms the topmost member of a column. It mediates between the column and the load thrusting down upon it, broadening the area of the column's supporting surface. The capital, projecting on each side as it rises to support the abacus, joins the usually square abacus and the usually circular shaft of the column. The capital may be convex, as in the Doric order; concave, as in the inverted bell of the Corinthian order; or scrolling out, as in the Ionic order. These form the three principal types on which all capitals in the classical tradition are based. The Composite order established in the 16th century on a hint from the Arch of Titus, adds Ionic volutes to Corinthian acanthus leaves.

Greco-Buddhism, or Graeco-Buddhism, is the cultural syncretism between Hellenistic culture and Buddhism, which developed between the 4th century BC and the 5th century AD in Gandhara, in present-day north-western Pakistan and parts of north-east Afghanistan.

The Maurya Empire was a geographically extensive Iron Age historical power in South Asia based in Magadha. Founded by Chandragupta Maurya in 322 BCE, it existed in loose-knit fashion until 185 BCE. The empire was centralized by the conquest of the Indo-Gangetic Plain; its capital city was located at Pataliputra. Outside this imperial centre, the empire's geographical extent was dependent on the loyalty of military commanders who controlled the armed cities scattered within it. During Ashoka's rule the empire briefly controlled the major urban hubs and arteries of the Indian subcontinent excepting the deep south. It declined for about 50 years after Ashoka's rule, and dissolved in 185 BCE with the assassination of Brihadratha by Pushyamitra Shunga and foundation of the Shunga dynasty in Magadha.

The Greco-Buddhist art or Gandhara art is the artistic manifestation of Greco-Buddhism, a cultural syncretism between Ancient Greek art and Buddhism. It had mainly evolved in the ancient region of Gandhara, located in the northwestern fringe of the Indian subcontinent.

The pillars of Ashoka are a series of monolithic columns dispersed throughout the Indian subcontinent, erected—or at least inscribed with edicts—by the 3rd Mauryan Emperor Ashoka the Great, who reigned from c. 268 to 232 BC. Ashoka used the expression Dhaṃma thaṃbhā, i.e. "pillars of the Dharma" to describe his own pillars. These pillars constitute important monuments of the architecture of India, most of them exhibiting the characteristic Mauryan polish. Twenty of the pillars erected by Ashoka still survive, including those with inscriptions of his edicts. Only a few with animal capitals survive of which seven complete specimens are known. Two pillars were relocated by Firuz Shah Tughlaq to Delhi. Several pillars were relocated later by Mughal Empire rulers, the animal capitals being removed. Averaging between 12 and 15 m in height, and weighing up to 50 tons each, the pillars were dragged, sometimes hundreds of miles, to where they were erected.

Pataliputra, adjacent to modern-day Patna, was a city in ancient India, originally built by Magadha ruler Ajatashatru in 490 BCE, as a small fort near the Ganges river. Udayin laid the foundation of the city of Pataliputra at the confluence of two rivers, the Son and the Ganges. He shifted his capital from Rajgriha to Pataliputra due to the latter's central location in the empire.

Sculpture in the Indian subcontinent, partly because of the climate of the Indian subcontinent makes the long-term survival of organic materials difficult, essentially consists of sculpture of stone, metal or terracotta. It is clear there was a great deal of painting, and sculpture in wood and ivory, during these periods, but there are only a few survivals. The main Indian religions had all, after hesitant starts, developed the use of religious sculpture by around the start of the Common Era, and the use of stone was becoming increasingly widespread.

Mauryan art is the art produced during the period of the Mauryan Empire, which was the first empire to rule over most of the Indian subcontinent, between 322 and 185 BCE. It represented an important transition in Indian art from use of wood to stone. It was a royal art patronized by Mauryan kings especially Ashoka. Pillars, Stupas, caves are the most prominent survivals.

Bead and reel is an architectural motif, usually found in sculptures, moldings and numismatics. It consists in a thin line where beadlike elements alternate with cylindrical ones. It is found throughout the modern Western world in architectural detail, particularly on Greek/Roman style buildings, wallpaper borders, and interior moulding design. It is often used in combination with the egg-and-dart motif.

Sarnath Museum is the oldest site museum of the Archaeological Survey of India. It houses the findings and excavations at the archaeological site of Sarnath, by the Archaeological Survey of India. Sarnath is located near Varanasi, in the state of Uttar Pradesh. The museum has 6,832 sculptures and artefacts.

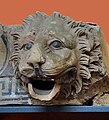

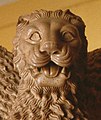

The Lion Capital of Ashoka is the capital, or head, of a column erected by the Mauryan emperor Ashoka in Sarnath, India, c. 250 BCE. Its crowning features are four life-sized lions set back to back on a drum-shaped abacus. The side of the abacus is adorned with wheels in relief, and interspersing them, four animals, a lion, an elephant, a bull, and a galloping horse follow each other from right to left. A bell-shaped lotus forms the lowest member of the capital, and the whole 2.1 metres (7 ft) tall, carved out of a single block of sandstone and highly polished, was secured to its monolithic column by a metal dowel. Erected after Ashoka's conversion to Buddhism, it commemorated the site of Gautama Buddha's first sermon some two centuries before.

The Achaemenid conquest of the Indus Valley refers to a process beginning in the 6th century BCE and ending in the 4th century BCE, whereby the Achaemenid Persian Empire established control over the northwestern regions of the Indian subcontinent, today predominantly comprising the territory of the Punjab region of the middle Indus Valley. The first of the two main invasions was conducted around 535 BCE by Cyrus the Great, who annexed the areas to the west of the Indus River, consolidating the early eastern border of the Achaemenid Empire. With a brief pause after Cyrus' death, the campaign continued under Darius the Great, who began to re-conquer former provinces and further expand Persia's political boundaries. Around 518 BCE, Persian armies under Darius crossed the Himalayas into India to initiate a second period of conquest by annexing regions up to Punjab.

The Pataliputra capital is a monumental rectangular capital with volutes and Classical Greek designs, that was discovered in the palace ruins of the ancient Mauryan Empire capital city of Pataliputra. It is dated to the 3rd century BCE.

Hellenistic influence on Indian art and architecture reflects the artistic and architectural influence of the Greeks on Indian art following the conquests of Alexander the Great, from the end of the 4th century BCE to the first centuries of the common era. The Greeks in effect maintained a political presence at the doorstep, and sometimes within India, down to the 1st century CE with the Greco-Bactrian Kingdom and the Indo-Greek Kingdoms, with many noticeable influences on the arts of the Maurya Empire especially. Hellenistic influence on Indian art was also felt for several more centuries during the period of Greco-Buddhist art.

The Stupa No. 2 at Sanchi, also called Sanchi II, is one of the oldest existing Buddhist stupas in India, and part of the Buddhist complex of Sanchi in Madhya Pradesh. It is of particular interest since it has the earliest known important displays of decorative reliefs in India, probably anterior to the reliefs at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, or the reliefs of Bharhut. It displays what has been called "the oldest extensive stupa decoration in existence". Stupa II at Sanchi is therefore considered as the birthplace of Jataka illustrations.

Mauryan polish describes one of the frequent characteristics of architecture and sculptures of the Maurya Empire in India, which gives a very smooth and shiny surface to the stone material, generally of sandstone or granite. Mauryan polish is found especially in the Ashoka Pillars as well as in some constructions like the Barabar Caves. The technique did not end with the empire, but continued to be "used on occasion up to the first or second century A.D.", although the presence of the polish sometimes complicates dating, as with the Didarganj Yakshi. According to the archaeologist John Marshall: the "extraordinary precision and accuracy which characterizes all Mauryan works, and which has never, we venture to say, been surpassed even by the finest workmanship on Athenian buildings".

The Sarnath capital is a pillar capital, sometimes also described as a "stone bracket", discovered in the archaeological excavations at the ancient Buddhist site of Sarnath in 1905. The pillar displays Ionic volutes and palmettes. It used to be dated to the 3rd century BCE, during the Mauryan Empire period, but is now dated to the 1st century BCE, during the Sunga Empire period.