Related Research Articles

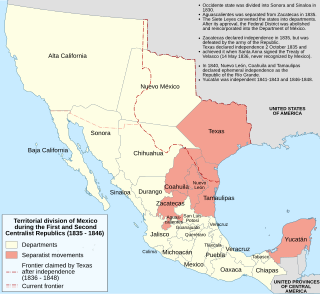

The Texas Revolution was a rebellion of colonists from the United States and Tejanos in putting up armed resistance to the centralist government of Mexico. While the uprising was part of a larger one, the Mexican Federalist War, that included other provinces opposed to the regime of President Antonio López de Santa Anna, the Mexican government believed the United States had instigated the Texas insurrection with the goal of annexation. The Mexican Congress passed the Tornel Decree, declaring that any foreigners fighting against Mexican troops "will be deemed pirates and dealt with as such, being citizens of no nation presently at war with the Republic and fighting under no recognized flag". Only the province of Texas succeeded in breaking with Mexico, establishing the Republic of Texas, and eventually being annexed by the United States.

The Battle of San Jacinto, fought on April 21, 1836, in present-day Pasadena, Texas, was the decisive battle of the Texas Revolution. Led by General Samuel Houston, the Texan Army engaged and defeated General Antonio López de Santa Anna's Mexican army in a fight that lasted just 18 minutes. A detailed, first-hand account of the battle was written by General Houston from the headquarters of the Texan Army in San Jacinto on April 25, 1836. Numerous secondary analyses and interpretations have followed.

The Goliad massacre was an event of the Texas Revolution that occurred on March 27, 1836, following the Battle of Coleto; 425–445 prisoners of war from the Texian Army of the Republic of Texas were executed by the Mexican Army in the town of Goliad, Texas. Among those killed was their commander Colonel James Fannin. The killing was carried out under orders from General and President of Mexico Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna. Despite the appeals for clemency by General José de Urrea, the massacre was reluctantly carried out by Lt. Colonel José Nicolás de la Portilla.

The Goliad Campaign was the 1836 Mexican offensive to retake the Texas Gulf Coast during the Texas Revolution. Mexican troops under the command of General José de Urrea defeated rebellious immigrants to the Mexican province of Texas, known as Texians, in a series of clashes in February and March.

James Walker Fannin Jr. was a 19th-century slave-trader and American military figure in the Texas Army and leader during the Texas Revolution of 1835–36. After being outnumbered and surrendering to Mexican forces at the Battle of Coleto Creek, Colonel Fannin and nearly all his 344 men were executed soon afterward at Goliad, Texas, under Santa Anna's orders for all rebels to be executed.

The Battle of Goliad was the second skirmish of the Texas Revolution. In the early-morning hours of October 9, 1835, Texas settlers attacked the Mexican Army soldiers garrisoned at Presidio La Bahía, a fort near the Mexican Texas settlement of Goliad. La Bahía lay halfway between the only other large garrison of Mexican soldiers and the then-important Texas port of Copano.

The Battle of San Patricio was fought on February 27, 1836, between Texian rebels and the Mexican army, during the Texas Revolution. The battle occurred as a result of the outgrowth of the Texian Matamoros Expedition. The battle marked the start of the Goliad Campaign, the Mexican offensive to retake the Texas Gulf Coast. It took place in and around San Patricio.

The Battle of Agua Dulce Creek was a skirmish during the Texas Revolution between Mexican troops and rebellious colonists of the Mexican province of Texas, known as Texians. As part of the Goliad Campaign to retake the Texas Gulf Coast, Mexican troops ambushed a group of Texians on March 2, 1836. The skirmish began approximately 26 miles (42 km) south of San Patricio, in territory belonging to the Mexican state of Tamaulipas.

The Runaway Scrape events took place mainly between September 1835 and April 1836 and were the evacuations by Texas residents fleeing the Mexican Army of Operations during the Texas Revolution, from the Battle of the Alamo through the decisive Battle of San Jacinto. The ad interim government of the new Republic of Texas and much of the civilian population fled eastward ahead of the Mexican forces. The conflict arose after Antonio López de Santa Anna abrogated the 1824 Constitution of Mexico and established martial law in Coahuila y Tejas. The Texians resisted and declared their independence. It was Sam Houston's responsibility, as the appointed commander-in-chief of the Provisional Army of Texas, to recruit and train a military force to defend the population against troops led by Santa Anna.

The Consultation, also known as the Texian Government, served as the provisional government of Mexican Texas from October 1835 to March 1836 during the Texas Revolution. Tensions rose in Texas during early 1835 as throughout Mexico federalists began to oppose the increasingly centralist policies of the government. In the summer, Texians elected delegates to a political convention to be held in Gonzales in mid-October. Weeks before the convention and war began, the Texian Militia took up arms against Mexican soldiers at the Battle of Gonzales. The convention was postponed until November 1 after many of the delegates joined the newly organized volunteer Texian Army to initiate a siege of the Mexican garrison at San Antonio de Bexar. On November 3, a quorum was reached in San Antonio. Within days, the delegates passed a resolution to define why Texians were fighting. They expressed allegiance to the deposed Constitution of 1824 and maintained their right to form the General Council. In the next weeks, the council authorized the creation of a new regular army to be commanded by Sam Houston. As Houston worked to establish an army independent from the existing volunteer army, the council repeatedly interfered in military matters.

The siege of Béxar was an early campaign of the Texas Revolution in which a volunteer Texian army defeated Mexican forces at San Antonio de Béxar. Texians had become disillusioned with the Mexican government as President and General Antonio López de Santa Anna's tenure became increasingly dictatorial. In early October 1835, Texas settlers gathered in Gonzales to stop Mexican troops from reclaiming a small cannon. The resulting skirmish, known as the Battle of Gonzales, launched the Texas Revolution. Men continued to assemble in Gonzales and soon established the Texian Army. Despite a lack of military training, well-respected local leader General Stephen F. Austin was elected commander.

The Texian Army, also known as the Revolutionary Army and Army of the People, was the land warfare branch of the Texian armed forces during the Texas Revolution. It spontaneously formed from the Texian Militia in October 1835 following the Battle of Gonzales. Along with the Texian Navy, it helped the Republic of Texas win independence from the Centralist Republic of Mexico on May 14, 1836 at the Treaties of Velasco. Although the Texas Army was officially established by the Consultation of the Republic of Texas on November 13, 1835, it did not replace the Texian Army until after the Battle of San Jacinto.

The Presidio Nuestra Señora de Loreto de la Bahía, known more commonly as Presidio La Bahía, or simply La Bahía is a fort constructed by the Spanish Army that became the nucleus of the modern-day city of Goliad, Texas, United States. The current location dates to 1747.

The Battle of Lipantitlán, also known as the Battle of Nueces Crossing, was fought along the Nueces River on November 4, 1835 between the Mexican Army and Texian insurgents, as part of the Texas Revolution. After the Texian victory at the Battle of Goliad, only two Mexican garrisons remained in Texas, Fort Lipantitlán near San Patricio and the Alamo Mission at San Antonio de Béxar. Fearing that Lipantitlán could be used as a base for the Mexican army to retake Goliad and angry that two of his men were imprisoned there, Texian commander Philip Dimmitt ordered his adjutant, Captain Ira Westover, to capture the fort.

Philip Dimmitt (1801–1841) was an officer in the Texian Army during the Texas Revolution. Born in Kentucky, Dimmitt moved to Texas in 1823 and soon operated a series of trading posts. After learning that Mexican General Martín Perfecto de Cos was en route to Texas in the year 1835 (??) to quell the unrest, Dimmitt proposed that the general be kidnapped on his arrival at Copano. The plan was shelved when fighting broke out at Gonzales, but by early October, 1835, it had been resuscitated by a group of volunteers at Matamoros. Not knowing that Cos had already departed for San Antonio de Bexar, this group decided to corner Cos at Presidio La Bahia in Goliad. Dimmitt joined them en route, and participated in the battle of Goliad.

Francis White "Frank" Johnson was a leader of the Texian Army from December 1835 through February 1836, during the Texas Revolution. Johnson arrived in Texas in 1826 and worked as a surveyor for several empresarios, including Stephen F. Austin. One of his first activities was to plot the new town of Harrisburg. Johnson unsuccessfully tried to prevent the Fredonian Rebellion and served as a delegate to the Convention of 1832.

Agustín Viesca (1790–1845) was a governor of the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas in 1835. He was the brother of José María Viesca, also a governor of Coahuila y Tejas during 1827-1831.

James Grant (1793–1836) was a 19th-century Texas politician, physician and military participant in the Texas Revolution.

The Texas Army, officially the Army of the Republic of Texas, was the land warfare branch of the Texas Military Forces during the Republic of Texas. It descended from the Texian Army, which was established in October 1835 to fight for independence from Centralist Republic of Mexico in the Texas Revolution. The Texas Army was provisionally formed by the Consultation in November 1835, however it did not replace the Texian Army until after the Battle of San Jacinto. The Texas Army, Texas Navy, and Texas Militia were officially established on September 5, 1836, in Article II of the Constitution of the Republic of Texas. The Texas Army and Texas Navy were merged with the United States Armed Forces on February 19, 1846, after the Republic of Texas became the 28th state of America.

References

- Hansen, Todd (2003). The Alamo Reader: A Study in History. Stackpole Books. ISBN 978-0-8117-0060-3.

- Hardin, Stephen L. (1994). Texian Iliad – A Military History of the Texas Revolution. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press. ISBN 0-292-73086-1.

- Huson, Hobart (1974). Captain Phillip Dimmitt's Commandancy of Goliad, 1835–1836. Von Boeckmann-Jones Co.

- Lack, Paul D. (1992), The Texas Revolutionary Experience: A Political and Social History 1835–1836, College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, ISBN 0-89096-497-1

- Reid, Stuart (2007). The Secret War for Texas. Elma Dill Russell Spencer Series in the West and Southwest. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-1-58544-565-3.

- Roell, Craig H (2013). Matamoros and the Texas Revolution. Denton, TX: Texas State Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-87611-260-1.

- Santos, Richard G. (1968). Santa Anna's campaign against Texas, 1835-1836;: Featuring the field commands issued to Major General Vicente Filisola (First ed.). Texian Press. ASIN B0006BV0Y8.

- Stuart, Jay (2008). Slaughter at Goliad: The Mexican Massacre of 400 Texas Volunteers. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-843-2.

- Winders, Richard Bruce (2004). Sacrificed at the Alamo: Tragedy and Triumph in the Texas Revolution. Military History of Texas Series: Number Three. Abilene, TX: State House Press. ISBN 1-880510-80-4.