The Panchatantra is an ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in Sanskrit verse and prose, arranged within a frame story. The surviving work is dated to roughly 200 BCE – 300 CE, based on older oral tradition. The text's author has been attributed to Vishnu Sharma in some recensions and Vasubhaga in others, both of which may be pen names. It is classical literature in a Hindu text, and based on older oral traditions with "animal fables that are as old as we are able to imagine".

The Arthashastra is an ancient Indian Sanskrit treatise on statecraft, economic policy and military strategy. Kautilya, also identified as Vishnugupta and Chanakya, is traditionally credited as the author of the text. The latter was a scholar at Takshashila, the teacher and guardian of Emperor Chandragupta Maurya. Some scholars believe them to be the same person, while most have questioned this identification. The text is likely to be the work of several authors over centuries. Composed, expanded and redacted between the 2nd century BCE and 3rd century CE, the Arthashastra was influential until the 12th century, when it disappeared. It was rediscovered in 1905 by R. Shamasastry, who published it in 1909. The first English translation, also by Shamasastry, was published in 1915.

Keļallur Nilakantha Somayaji, also referred to as Keļallur Comatiri, was a major mathematician and astronomer of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics. One of his most influential works was the comprehensive astronomical treatise Tantrasamgraha completed in 1501. He had also composed an elaborate commentary on Aryabhatiya called the Aryabhatiya Bhasya. In this Bhasya, Nilakantha had discussed infinite series expansions of trigonometric functions and problems of algebra and spherical geometry. Grahapariksakrama is a manual on making observations in astronomy based on instruments of the time. Known popularly as Kelallur Chomaathiri, he is considered an equal to Vatasseri Parameshwaran Nambudiri.

Jyeṣṭhadeva was an astronomer-mathematician of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics founded by Madhava of Sangamagrama. He is best known as the author of Yuktibhāṣā, a commentary in Malayalam of Tantrasamgraha by Nilakantha Somayaji (1444–1544). In Yuktibhāṣā, Jyeṣṭhadeva had given complete proofs and rationale of the statements in Tantrasamgraha. This was unusual for traditional Indian mathematicians of the time. The Yuktibhāṣā is now believed to contain the essential elements of the calculus and one of the earliest treatise on the subject. Jyeṣṭhadeva also authored Drk-karana a treatise on astronomical observations.

The Harivansha is an important work of Sanskrit literature, containing 16,374 shlokas, mostly in the anustubh metre. The text is also known as the Harivansha Purana. This text is believed to be a khila to the Mahabharata and is traditionally ascribed to Vyasa. The most celebrated commentary of the Mahabharata by Neelakantha Chaturdhara, the Bharata Bhava Deepa also covers the Harivansha. According to a traditional version of the Mahabharata, the Harivansha is divided into two parvas (books) and 12,000 verses. These are included with the eighteen parvas of the Mahabharata. The Critical Edition has three parvas and 5,965 verses.

Brihaddeshi is a Classical Sanskrit text, dated ca. 6th to 8th century CE, on Indian classical music, attributed to Mataṅga Muni. It is the first text to speak directly of the raga and to distinguish marga ("classical") from desi ("folk") music. It also introduced sargam solfège, the singing of the first syllable of the names of the musical notes, as an aid to learning and performance.

Dāsbodh, loosely meaning "advice to the disciple" in Marathi, is a 17th-century bhakti (devotion) and jnana (insight) spiritual text. It was orally narrated by the saint Samarth Ramdas to his disciple, Kalyan Swami. The Dāsbodh provides readers with spiritual guidance on matters such as devotion and acquiring knowledge. Besides this, it also helps in answering queries related to day-to-day life and how to find solutions to it.

Gheranda Samhita is a Sanskrit text of Yoga in Hinduism. It is one of the three classic texts of hatha yoga, and one of the most encyclopedic treatises in yoga. Fourteen manuscripts of the text are known, which were discovered in a region stretching from Bengal to Rajasthan. The first critical edition was published in 1933 by Adyar Library, and the second critical edition was published in 1978 by Digambarji and Ghote. Some of the Sanskrit manuscripts contain ungrammatical and incoherent verses, and some cite older Sanskrit texts.

Yuktibhāṣā, also known as Gaṇitanyāyasaṅgraha, is a major treatise on mathematics and astronomy, written by the Indian astronomer Jyesthadeva of the Kerala school of mathematics around 1530. The treatise, written in Malayalam, is a consolidation of the discoveries by Madhava of Sangamagrama, Nilakantha Somayaji, Parameshvara, Jyeshtadeva, Achyuta Pisharati, and other astronomer-mathematicians of the Kerala school.

Tantrasamgraha, or Tantrasangraha, is an important astronomical treatise written by Nilakantha Somayaji, an astronomer/mathematician belonging to the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics. The treatise was completed in 1501 CE. It consists of 432 verses in Sanskrit divided into eight chapters. Tantrasamgraha had spawned a few commentaries: Tantrasamgraha-vyakhya of anonymous authorship and Yuktibhāṣā authored by Jyeshtadeva in about 1550 CE. Tantrasangraha, together with its commentaries, bring forth the depths of the mathematical accomplishments the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics, in particular the achievements of the remarkable mathematician of the school Sangamagrama Madhava. In his Tantrasangraha, Nilakantha revised Aryabhata's model for the planets Mercury and Venus. His equation of the centre for these planets remained the most accurate until the time of Johannes Kepler in the 17th century.

Shiva Samhita is a Sanskrit text on yoga, written by an unknown author. The text is addressed by the Hindu god Shiva to his consort Parvati. The text consists of five chapters, with the first chapter a treatise that summarizes nondual Vedanta philosophy with influences from the Sri Vidya school of South India. The remaining chapters discuss yoga, the importance of a guru (teacher) to a student, various asanas, mudras and siddhis (powers) attainable with yoga and tantra.

Nandikeshvara was a major theatrologist of ancient India. He was the author of the Abhinaya Darpanalit. 'The Mirror of Gesture'.

The Shalihotra Samhita is an early Indian treatise on veterinary medicine (hippiatrics), likely composed in the 3rd century BCE.

Sanskrit prosody or Chandas refers to one of the six Vedangas, or limbs of Vedic studies. It is the study of poetic metres and verse in Sanskrit. This field of study was central to the composition of the Vedas, the scriptural canons of Hinduism, so central that some later Hindu and Buddhist texts refer to the Vedas as Chandas.

Karanapaddhati is an astronomical treatise in Sanskrit attributed to Puthumana Somayaji, an astronomer-mathematician of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics. The period of composition of the work is uncertain. C.M. Whish, a civil servant of the East India Company, brought this work to the attention of European scholars for the first time in a paper published in 1834. The book is divided into ten chapters and is in the form of verses in Sanskrit. The sixth chapter contains series expansions for the value of the mathematical constant π, and expansions for the trigonometric sine, cosine and inverse tangent functions.

Ganita-yukti-bhasa is either the title or a part of the title of three different books:

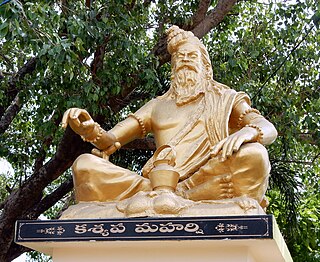

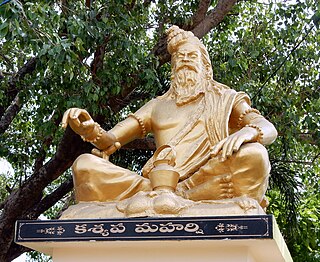

Kashyapa is a revered Vedic sage of Hinduism. He is one of the Saptarishis, the seven ancient sages of the Rigveda, as well as numerous other Sanskrit texts and Indian Religious books. He is the most ancient Rishi listed in the colophon verse in the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

Kriyakramakari (Kriyā-kramakarī) is an elaborate commentary in Sanskrit written by Sankara Variar and Narayana, two astronomer-mathematicians belonging to the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics, on Bhaskara II's well-known textbook on mathematics Lilavati. Kriyakramakari, along with Yuktibhasa of Jyeshthadeva, is one of the main sources of information about the work and contributions of Sangamagrama Madhava, the founder of Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics. Also the quotations given in this treatise throw much light on the contributions of several mathematicians and astronomers who had flourished in an earlier era. There are several quotations ascribed to Govindasvami a 9th-century astronomer from Kerala.

Temporins are a family of peptides isolated originally from the skin secretion of the European red frog, Rana temporaria. Peptides belonging to the temporin family have been isolated also from closely related North American frogs, such as Rana sphenocephala.

Jatakalankara is a brief Sanskrit treatise comprising one hundred twenty-five slokas or verses on the predictive part of Hindu astrology written in the classic Sloka format in the Srgdhara meter. It was written by Poet Ganesa, son of Gopal Das, in the year 1613 and describes many yoga-formations that have immediate bearing on various aspects of human life. Ganesha wrote this treatise to please his Guru Shiva Its first translation into English was probably published, along with the original text, in 1941 by Sri Vijay Lakshmi Vilas Press.