Luca della Robbia was an Italian Renaissance sculptor from Florence. Della Robbia is noted for his colorful, tin-glazed terracotta statuary, a technique that he invented and passed on to his nephew Andrea della Robbia and great-nephews Giovanni della Robbia and Girolamo della Robbia. Although a leading sculptor in stone, after developing his technique in the early 1440s he worked primarily in terracotta. His large workshop produced both less expensive works cast from molds in multiple versions, and more expensive one-off individually modeled pieces.

Luca Signorelli was an Italian Renaissance painter from Cortona, in Tuscany, who was noted in particular for his ability as a draftsman and his use of foreshortening. His massive frescos of the Last Judgment (1499–1503) in Orvieto Cathedral are considered his masterpiece.

Piero del Pollaiuolo, whose birth name was Piero Benci, was an Italian Renaissance painter from Florence. His older brother, by about ten years, was the artist Antonio del Pollaiuolo and the two frequently worked together. Their work shows both classical influences and an interest in human anatomy; according to Vasari, the brothers carried out dissections to improve their knowledge of the subject.

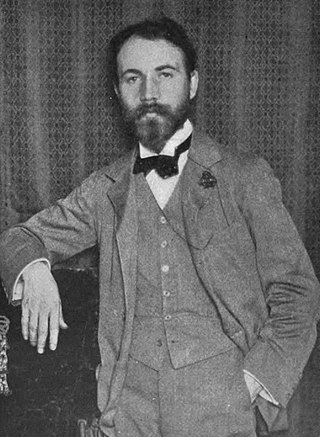

Bernard Berenson was an American art historian specializing in the Renaissance. His book The Drawings of the Florentine Painters was an international success. His wife Mary is thought to have had a large hand in some of the writings.

Giovanni Morelli was an Italian art critic and political figure. As an art historian, he developed the "Morellian" technique of scholarship, identifying the characteristic "hands" of painters through scrutiny of diagnostic minor details that revealed artists' scarcely conscious shorthand and conventions for portraying, for example, ears. He was born in Verona and died in Milan.

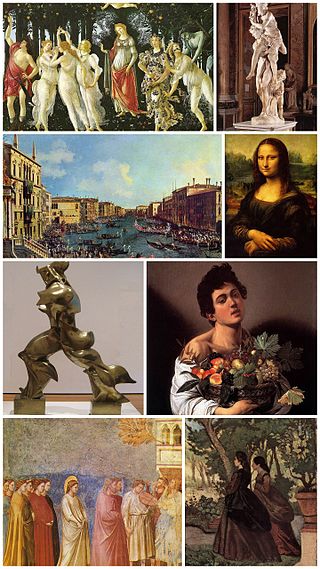

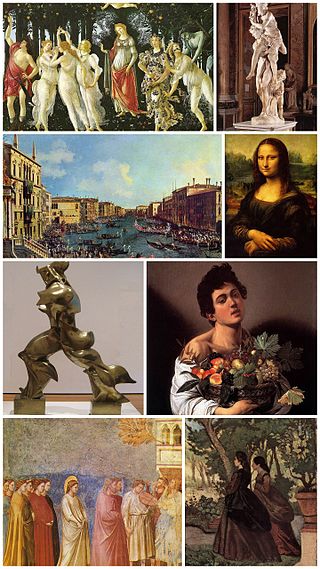

The cultural and artistic events of Italy during the period 1400 to 1499 are collectively referred to as the Quattrocento from the Italian word for the number 400, in turn from millequattrocento, which is Italian for the year 1400. The Quattrocento encompasses the artistic styles of the late Middle Ages, the early Renaissance, and the start of the High Renaissance, generally asserted to begin between 1495 and 1500.

Vernon Lee was the pseudonym of the British writer Violet Paget. She is remembered today primarily for her supernatural fiction and her work on aesthetics. An early follower of Walter Pater, she wrote over a dozen volumes of essays on art, music and travel.

Andrea della Robbia was an Italian Renaissance sculptor, especially in ceramics.

The Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, often simply known as The Lives, is a series of artist biographies written by 16th-century Italian painter and architect Giorgio Vasari, which is considered "perhaps the most famous, and even today the most-read work of the older literature of art", "some of the Italian Renaissance's most influential writing on art", and "the first important book on art history".

Mary Berenson was an American art historian, now thought to have had a large hand in some of the writings of her second husband, Bernard Berenson.

Christiana Jane Herringham, Lady Herringham was a British artist, copyist, and art patron. She is noted for her part in establishing the National Art Collections Fund in 1903 to help preserve Britain's artistic heritage. In 1910 Walter Sickert wrote of her as "the most useful and authoritative critic living".

Julia Mary Cartwright Ady was a British historian and art critic whose work focused on the Italian Renaissance.

Villa I Tatti, The Harvard Center for Italian Renaissance Studies is a center for advanced research in the humanities located in Florence, Italy, and belongs to Harvard University. It houses a collection of Italian primitives, and of Chinese and Islamic art, as well as a research library of 140,000 volumes and a collection of 250,000 photographs. It is the site of Italian and English gardens. Villa I Tatti is located on an estate of olive groves, vineyards, and gardens on the border of Florence, Fiesole and Settignano.

Karin Stephen was a British psychoanalyst and psychologist.

The Pinacoteca Comunale ofCittà di Castello is the main museum of paintings and arts of Umbria Italian Region, alongside the Perugia's National gallery, and it's housed in a renaissance palace, generally preserved in its original form.

Profile Portrait of a Young Lady is a 1465 half-length portrait, made with oil-based paint and tempera on a poplar panel, usually attributed to Antonio del Pollaiuolo, although the owning museum, the Gemäldegalerie in Berlin, now describes this work as by his brother Piero del Pollaiuolo, and as one of its most famous paintings, and as one of the most famous portraits of women from the early Italian Renaissance.

Adoration of the Magi is a painting in tempera on wood panel by Luca Signorelli (1450–1523) and his assistants, executed c. 1493–1494, and now in the Louvre in Paris. It was probably the first painting he produced in Città di Castello, and originally hung over the main altar of the monastery church of Sant'Agostino. The surface displayed within the frame is 331 cm by 245.5 cm. In late 2022 it was not on display.

Constance Jocelyn Ffoulkes (1858–1950) was a British art historian, translator, and scholar of Italian Renaissance art. She participated in the adoption of the 'historical standpoint' method of research, a shift in art criticism that emerged in the early twentieth century. She was a student of Giovanni Morelli and his methods of connoisseurship, which involved assembling subtle clues and recognition of personal technique, the artist's 'hand', to determine a work's provenance and creators. She translated Morelli's Kunstkritische Studien über italienische Malerei and was instrumental in the communication of Morelli's methods and legacy.

Luisa Vertova was an Italian art historian. Her research work mostly focused on Renaissance Italian painters such as Piero della Francesca, Mantegna, Paolo Veronese, Titian, Botticelli and Caravaggio. In addition, she undertook numerous projects as editor of several editions of her mentor Bernard Berenson's and her husband Benedict Nicolson's writings.

Lucy Olcott (1877–1922) was an American art historian and dealer who specialized in the art of Siena as well as Egyptian antiquities, working for both the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Cleveland Museum of Art. She was co-author of the widely-read Guide to Siena, published in 1903.