Related Research Articles

Existence is the state of having being or reality in contrast to nonexistence and nonbeing. Existence is often contrasted with essence: the essence of an entity is its essential features or qualities, which can be understood even if one does not know whether the entity exists.

Understood in a narrow sense, philosophical logic is the area of logic that studies the application of logical methods to philosophical problems, often in the form of extended logical systems like modal logic. Some theorists conceive philosophical logic in a wider sense as the study of the scope and nature of logic in general. In this sense, philosophical logic can be seen as identical to the philosophy of logic, which includes additional topics like how to define logic or a discussion of the fundamental concepts of logic. The current article treats philosophical logic in the narrow sense, in which it forms one field of inquiry within the philosophy of logic.

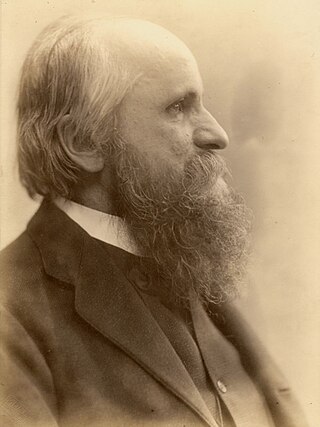

Alexius Meinong Ritter von Handschuchsheim was an Austrian philosopher, a realist known for his unique ontology and theory of objects. He also made contributions to philosophy of mind and theory of value.

Richard Sylvan was a New Zealand–born philosopher, logician, and environmentalist.

Truthmaker theory is "the branch of metaphysics that explores the relationships between what is true and what exists". The basic intuition behind truthmaker theory is that truth depends on being. For example, a perceptual experience of a green tree may be said to be true because there actually is a green tree. But if there were no tree there, it would be false. So the experience by itself does not ensure its truth or falsehood, it depends on something else. Expressed more generally, truthmaker theory is the thesis that "the truth of truthbearers depends on the existence of truthmakers". A perceptual experience is the truthbearer in the example above. Various representational entities, like beliefs, thoughts or assertions can act as truthbearers. Truthmaker theorists are divided about what type of entity plays the role of truthmaker; popular candidates include states of affairs and tropes.

The Graz School, also Meinong's School, of experimental psychology and object theory was headed by Alexius Meinong, who was professor and Chair of Philosophy at the University of Graz where he founded the Graz Psychological Institute in 1894. The Graz School's phenomenological psychology and philosophical semantics achieved important advances in philosophy and psychological science.

In analytic philosophy, actualism is the view that everything there is is actual. Another phrasing of the thesis is that the domain of unrestricted quantification ranges over all and only actual existents.

Philosophical realism – usually not treated as a position of its own but as a stance towards other subject matters – is the view that a certain kind of thing has mind-independent existence, i.e. that it exists even in the absence of any mind perceiving it or that its existence is not just a mere appearance in the eye of the beholder. This includes a number of positions within epistemology and metaphysics which express that a given thing instead exists independently of knowledge, thought, or understanding. This can apply to items such as the physical world, the past and future, other minds, and the self, though may also apply less directly to things such as universals, mathematical truths, moral truths, and thought itself. However, realism may also include various positions which instead reject metaphysical treatments of reality entirely.

Modal realism is the view propounded by philosopher David Lewis that all possible worlds are real in the same way as is the actual world: they are "of a kind with this world of ours." It is based on four tenets: possible worlds exist, possible worlds are not different in kind from the actual world, possible worlds are irreducible entities, and the term actual in actual world is indexical, i.e. any subject can declare their world to be the actual one, much as they label the place they are "here" and the time they are "now".

A free logic is a logic with fewer existential presuppositions than classical logic. Free logics may allow for terms that do not denote any object. Free logics may also allow models that have an empty domain. A free logic with the latter property is an inclusive logic.

Kaarlo Jaakko Juhani Hintikka was a Finnish philosopher and logician. Hintikka is regarded as the founder of formal epistemic logic and of game semantics for logic.

Ernst Mally was an Austrian analytic philosopher, initially affiliated with Alexius Meinong's Graz School of object theory. Mally was one of the founders of deontic logic and is mainly known for his contributions in that field of research. In metaphysics, he is known for introducing a distinction between two kinds of predication, better known as the dual predication approach.

In metaphysics and ontology, nonexistent objects are a concept advanced by Austrian philosopher Alexius Meinong in the 19th and 20th centuries within a "theory of objects". He was interested in intentional states which are directed at nonexistent objects. Starting with the "principle of intentionality", mental phenomena are intentionally directed towards an object. People may imagine, desire or fear something that does not exist. Other philosophers concluded that intentionality is not a real relation and therefore does not require the existence of an object, while Meinong concluded there is an object for every mental state whatsoever—if not an existent then at least a nonexistent one.

Noneism, also known as modal Meinongianism, is a theory in logic and metaphysics. It holds that some things do not exist. It was first coined by Richard Routley in 1980 and appropriated again in 2005 by Graham Priest.

Héctor-Neri Castañeda was a Guatemalan-American philosopher and founder of the journal Noûs.

William Joseph Rapaport is a North American philosopher who is an Associate Professor Emeritus of the University at Buffalo.

In metaphysics, Plato's beard is a paradoxical argument dubbed by Willard Van Orman Quine in his 1948 paper "On What There Is". The phrase came to be identified as the philosophy of understanding something based on what does not exist.

Abstract object theory (AOT) is a branch of metaphysics regarding abstract objects. Originally devised by metaphysician Edward Zalta in 1981, the theory was an expansion of mathematical Platonism.

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the study of deductively valid inferences or logical truths. It examines how conclusions follow from premises based on the structure of arguments alone, independent of their topic and content. Informal logic is associated with informal fallacies, critical thinking, and argumentation theory. Informal logic examines arguments expressed in natural language whereas formal logic uses formal language. When used as a countable noun, the term "a logic" refers to a specific logical formal system that articulates a proof system. Logic plays a central role in many fields, such as philosophy, mathematics, computer science, and linguistics.

The Meinongian argument is a type of ontological argument or an "a priori argument" that seeks to prove the existence of God. This is through an assertion that there is "a distinction between different categories of existence." The premise of the ontological argument is based on Alexius Meinong's works. Some scholars also associate it with St. Anselm's ontological argument.

References

- 1 2 3 Jacquette, Dale (1996). "On Defoliating Meinong's Jungle". Axiomathes. 7 (1–2): 17–42. doi:10.1007/BF02357196. S2CID 121956019.

- 1 2 Kneale, William C. (1949). Probability and Induction. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 12. OCLC 907671.

- ↑ Hacker, P. M. S. (1986). Insight and Illusion. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-19-824783-4.

- ↑ Klima, Gyula (2001). "Existence and Reference in Medieval Logic". In Lambert, Karel (ed.). New Essays in Free Logic. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. p. 211. ISBN 1-4020-0216-5.

- ↑ McGinn, Colin (1993). The Problem of Consciousness. Oxford: Blackwell. p. 105. ISBN 0-631-18803-7.

- ↑ Smith, A. D. (2002). The Problem of Perception. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. p. 240. ISBN 0-674-00841-3.

Gilbert Ryle once referred to Meinong as 'the supreme entity-multiplier in the history of philosophy', and Keith Donnellan alludes to 'the Meinongian population explosion', both thereby expressing a common view that lies behind the bon mot that we should cut back Meinong's jungle with Occam's razor.

- ↑ See also Plato's beard in W. V. O. Quine, "On What There Is", The Review of Metaphysics2 (5), 1948.

- ↑ Hintikka, Jaakko (1989). The Logic of Epistemology and the Epistemology of Logic. Kluwer Academic. p. 40. ISBN 0-7923-0040-8.