In chemistry, a carbene is a molecule containing a neutral carbon atom with a valence of two and two unshared valence electrons. The general formula is R-(C:)-R' or R=C: where the R represent substituents or hydrogen atoms.

The Sonogashira reaction is a cross-coupling reaction used in organic synthesis to form carbon–carbon bonds. It employs a palladium catalyst as well as copper co-catalyst to form a carbon–carbon bond between a terminal alkyne and an aryl or vinyl halide.

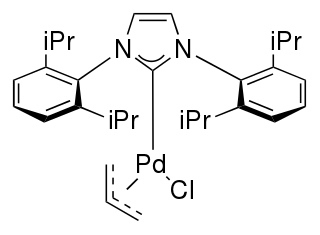

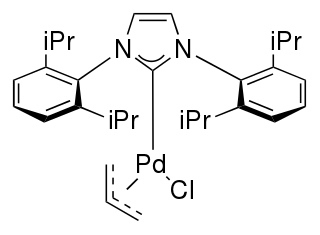

Grubbs catalysts are a series of transition metal carbene complexes used as catalysts for olefin metathesis. They are named after Robert H. Grubbs, the chemist who supervised their synthesis. Several generations of the catalyst have been developed. Grubbs catalysts tolerate many functional groups in the alkene substrates, are air-tolerant, and are compatible with a wide range of solvents. For these reasons, Grubbs catalysts have become popular in synthetic organic chemistry. Grubbs, together with Richard R. Schrock and Yves Chauvin, won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in recognition of their contributions to the development of olefin metathesis.

Organoborane or organoboron compounds are chemical compounds of boron and carbon that are organic derivatives of BH3, for example trialkyl boranes. Organoboron chemistry or organoborane chemistry is the chemistry of these compounds.

A transition metal carbene complex is an organometallic compound featuring a divalent organic ligand. The divalent organic ligand coordinated to the metal center is called a carbene. Carbene complexes for almost all transition metals have been reported. Many methods for synthesizing them and reactions utilizing them have been reported. The term carbene ligand is a formalism since many are not derived from carbenes and almost none exhibit the reactivity characteristic of carbenes. Described often as M=CR2, they represent a class of organic ligands intermediate between alkyls (−CR3) and carbynes (≡CR). They feature in some catalytic reactions, especially alkene metathesis, and are of value in the preparation of some fine chemicals.

A persistent carbene (also known as stable carbene) is a type of carbene demonstrating particular stability. The best-known examples and by far largest subgroup are the N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC) (sometimes called Arduengo carbenes), for example diaminocarbenes with the general formula (R2N)2C:, where the 'R's are typically alkyl and aryl groups. The groups can be linked to give heterocyclic carbenes, such as those derived from imidazole, imidazoline, thiazole or triazole.

A migratory insertion is a type of reaction in organometallic chemistry wherein two ligands on a metal complex combine. It is a subset of reactions that very closely resembles the insertion reactions, and both are differentiated by the mechanism that leads to the resulting stereochemistry of the products. However, often the two are used interchangeably because the mechanism is sometimes unknown. Therefore, migratory insertion reactions or insertion reactions, for short, are defined not by the mechanism but by the overall regiochemistry wherein one chemical entity interposes itself into an existing bond of typically a second chemical entity e.g.:

Organoruthenium chemistry is the chemistry of organometallic compounds containing a carbon to ruthenium chemical bond. Several organoruthenium catalysts are of commercial interest and organoruthenium compounds have been considered for cancer therapy. The chemistry has some stoichiometric similarities with organoiron chemistry, as iron is directly above ruthenium in group 8 of the periodic table. The most important reagents for the introduction of ruthenium are ruthenium(III) chloride and triruthenium dodecacarbonyl.

Guy Bertrand, born on July 17, 1952 at Limoges is a chemistry professor at the University of California, San Diego.

An insertion reaction is a chemical reaction where one chemical entity interposes itself into an existing bond of typically a second chemical entity e.g.:

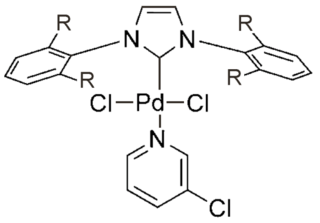

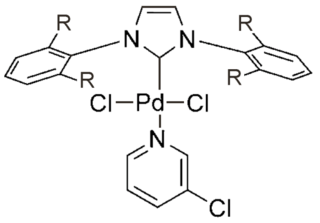

PEPPSI is an abbreviation for pyridine-enhanced precatalyst preparation stabilization and initiation. It refers to a group of palladium catalysts developed around 2005 by Prof. Michael G. Organ and co-workers at York University, which can accelerate various aminations and cross-coupling reactions. In comparison to many alternative palladium catalysts, PEPPSI-type complexes are stable to air and moisture and are relatively easy to synthesize and handle.

The Tolman electronic parameter (TEP) is a measure of the electron donating or withdrawing ability of a ligand. It is determined by measuring the frequency of the A1 C-O vibrational mode (ν(CO)) of a (pseudo)-C3v symmetric complex, [LNi(CO)3] by infrared spectroscopy, where L is the ligand of interest. [LNi(CO)3] was chosen as the model compound because such complexes are readily prepared from tetracarbonylnickel(0). The shift in ν(CO) is used to infer the electronic properties of a ligand, which can aid in understanding its behavior in other complexes. The analysis was introduced by Chadwick A. Tolman.

Diiminopyridines are a class of diimine ligands. They featuring a pyridine nucleus with imine sidearms appended to the 2,6–positions. The three nitrogen centres bind metals in a tridentate fashion, forming pincer complexes. Diiminopyridines are notable as non-innocent ligand that can assume more than one oxidation state. Complexes of DIPs participate in a range of chemical reactions, including ethylene polymerization, hydrosilylation, and hydrogenation.

In organometallic chemistry, palladium-NHC complexes are a family of organopalladium compounds in which palladium forms a coordination complex with N-Heterocyclic carbenes (NHCs). They have been investigated for applications in homogeneous catalysis, particularly cross-coupling reactions.

In coordination chemistry, a transition metal NHC complex is a metal complex containing one or more N-heterocyclic carbene ligands. Such compounds are the subject of much research, in part because of prospective applications in homogeneous catalysis. One such success is the second generation Grubbs catalyst.

A Zhan catalyst is a type of ruthenium-based organometallic complex used in olefin metathesis. This class of chemicals is named after the chemist who first synthesized them, Zheng-Yun J. Zhan.

Janis Louie is a Chemistry professor and Henry Eyring Fellow at The University of Utah. Louie contributes to the chemistry world with her research in inorganic, organic, and polymer chemistry.

In chemistry, cyclic(alkyl)(amino)carbenes (CAACs) are a family of stable singlet carbene ligands developed by Prof. Guy Bertrand and his group in 2005 at UC Riverside. In marked contrast with the popular N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC) which possess two "amino" substituents adjacent to the "carbene" center, CAACs possess one "amino" substituent and an sp3 carbon atom "alkyl". This specific configuration makes the CAACs very good σ-donors and π-acceptors when compared to NHCs. Moreover the reduced heteroatom stabilization of the carbene center in CAACs versus NHCs also gives rise to a smaller ΔEST.

A borylene is the boron analogue of a carbene. The general structure is R-B: with R an organic residue and B a boron atom with two unshared electrons. Borylenes are of academic interest in organoboron chemistry. A singlet ground state is predominant with boron having two vacant sp2 orbitals and one doubly occupied one. With just one additional substituent the boron is more electron deficient than the carbon atom in a carbene. For this reason stable borylenes are more uncommon than stable carbenes. Some borylenes such as boron monofluoride (BF) and boron monohydride (BH) the parent compound also known simply as borylene, have been detected in microwave spectroscopy and may exist in stars. Other borylenes exist as reactive intermediates and can only be inferred by chemical trapping.

Transition metal isocyanide complexes are coordination compounds containing isocyanide ligands. Because isocyanide are relatively basic, but also good pi-acceptors, a wide range of complexes are known. Some isocyanide complexes are used in medical imaging.