Eskimo or Eskimos are the indigenous peoples who have traditionally inhabited the northern circumpolar region from eastern Siberia (Russia) to across Alaska, Canada, and Greenland.

The Yupik are a group of indigenous or aboriginal peoples of western, southwestern, and southcentral Alaska and the Russian Far East. They are Eskimo and are related to the Inuit and Iñupiat peoples. Yupik peoples include the following:

The Iñupiat are native Alaskan people, whose traditional territory spans Norton Sound on the Bering Sea to the Canada–United States border. Their current communities include seven Alaskan villages in the North Slope Borough, affiliated with the Arctic Slope Regional Corporation; eleven villages in Northwest Arctic Borough; and sixteen villages affiliated with the Bering Straits Regional Corporation.

Deg Hitʼan is a group of Yupikized Athabaskan peoples in Alaska. Their native language is called Deg Xinag. They reside in Alaska along the Anvik River in Anvik, along the Innoko River in Shageluk, and at Holy Cross along the lower Yukon River.

The Alaska Native Language Center, established in 1972 in Fairbanks, Alaska, is a research center focusing on the research and documentation of the Native languages of Alaska. It publishes grammars, dictionaries, folklore collections and research materials, as well as hosting an extensive archive of written materials relating to Eskimo, North Athabaskan and related languages. The Center provides training, materials and consultation for educators, researchers and others working with Alaska Native languages. The closely affiliated Alaska Native Language Program offers degrees in Central Yup'ik and Inupiaq at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, and works toward the documentation and preservation of these languages.

Inu-Yupiaq is a dance group at the University of Alaska, Fairbanks that performs a fusion of Iñupiaq and Yup’ik Eskimo motion dance.

The Yup'ik or Yupiaq and Yupiit or Yupiat (pl), also Central Alaskan Yup'ik, Central Yup'ik, Alaskan Yup'ik, are an Eskimo people of western and southwestern Alaska ranging from southern Norton Sound southwards along the coast of the Bering Sea on the Yukon-Kuskokwim Delta and along the northern coast of Bristol Bay as far east as Nushagak Bay and the northern Alaska Peninsula at Naknek River and Egegik Bay. They are also known as Cup'ik by the Chevak Cup'ik dialect-speaking Eskimos of Chevak and Cup'ig for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect-speaking Eskimo of Nunivak Island.

Nalukataq is the spring whaling festival of the Iñupiat Eskimos of Northern Alaska, especially the North Slope Borough. It is characterized by its namesake, the dramatic Eskimo blanket toss. "Marking the end of the spring whaling season," Nalukataq creates, "a sense of being for the entire community and for all who want a little muktuk or to take part in the blanket toss....At no time, however, does Nalukataq relinquish its original purpose, which is to recognize the annual success and prowess of each umialik, or whaling crew captain....Nalukataq [traditions] have always reflected the process of survival inherent in sharing...crucial to...the Arctic."

Nunivak Cup'ig or just Cup'ig is a language or separate dialect of Central Alaskan Yup'ik spoken in Central Alaska at the Nunivak Island by Nunivak Cup'ig people. The letter "c" in the Yup’ik alphabet is equivalent to the English alphabet "ch".

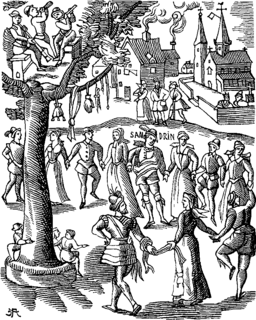

Qargi, Qasgi or Qasgiq, Qaygiq, Kashim, Kariyit, a traditional large semi-subterranean men's community house' of the Yup'ik and Inuit, also Deg Hit'an Athabaskans, was used for public and ceremonial occasions and as a men’s residence. The Qargi was the place where men built their boats, repaired their equipment, took sweat baths, educated young boys, and hosted community dances. Here people learned their oral history, songs and chants. Young boys and men learned to make tools and weapons while they listened to the traditions of their forefathers.

A kuspuk is a hooded overshirt with a large front pocket commonly worn among Alaska Natives. Kuspuks are tunic-length, falling anywhere from below the hips to below the knees. The bottom portion of kuspuks worn by women may be gathered and akin to a skirt. Kuspuks tend to be pullover garments, though some have zippers.

The Bladder Festival or Bladder Feast, is an important annual seal hunting harvest renewal ceremony and celebration held each year to honor and appease the souls of seals taken in the hunt during the past season which occurred at the winter solstice by the Yup'ik of western and southwestern Alaska.

Yup'ik masks are expressive shamanic ritual masks made by the Yup'ik people of southwestern Alaska. Also known as Cup'ik masks for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking Eskimos of Chevak and Cup'ig masks for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking Eskimos of Nunivak Island. One of their most popular forms of the Alaska Native art are masks. The Yup'ik masks vary enormously but are characterised by great invention. They are typically made of wood, and painted with few colors. The Yup'ik masks were carved by men or women, but mainly were carved by the men. The shamans (angalkuq) were the ones that told the carvers how to make the masks. Yup'ik masks could be small three-inch finger masks or maskettes, but also ten-kilo masks hung from the ceiling or carried by several people. These masks are used to bring the person wearing it luck and good fortune in hunts. Over the long winter darkness dances and storytelling took place in the qasgiq using these masks. They most often create masks for ceremonies but the masks are traditionally destroyed after being used. After Christian contact in the late nineteenth century, masked dancing was suppressed, and today it is not practiced as it was before in the Yup'ik villages.

Athabaskan fiddle is the old-time fiddle style which the Alaskan Athabaskans of the Interior Alaska have developed to play the fiddle (violin), solo and in folk ensembles. Fiddles were introduced in this area by Scottish, Irish, French Canadian, and Métis fur traders of the Hudson's Bay Company in the mid-19th century. Athabaskan fiddling is a variant of fiddling of the American southlands. Athabaskan fiddle music is most popular genre in Alaska and northwest Canada and featuring Gwich'in Bill Stevens and Trimble Gilbert.

Yup'ik dancing or Yuraq, also Yuraqing is a traditional Eskimo style dancing form usually performed to songs in Yup'ik, with dances choreographed for specific songs which the Yup'ik people of southwestern Alaska. Also known as Cup'ik dance for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking Eskimos of Chevak and Cup'ig dance for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking Eskimos of Nunivak Island. Yup'ik dancing is set up in a very specific and cultural format. Typically, the men are in the front, kneeling and the women stand in the back. The drummers are in the very back of the dance group. Dance is the heart of Yup’ik spiritual and social life. Every song has a story behind it and some songs is either about hunting or berry picking. Some songs could be about sports or other things that don't really relate to hunting. Traditional dancing in the qasgiq is a communal activity in Yup’ik tradition. The mask (kegginaquq) was a central element in Yup'ik ceremonial dancing.

Yup'ik doll is a traditional Eskimo style doll and figurine form made in the southwestern Alaska by Yup'ik people. Also known as Cup'ik doll for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking Eskimos of Chevak and Cup'ig doll for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking Eskimos of Nunivak Island. Typically, Yup'ik dolls are dressed in traditional Eskimo style Yup'ik clothing, intended to protect the wearer from cold weather, and are often made from traditional materials obtained through food gathering. Play dolls from the Yup'ik area were made of wood, bone, or walrus ivory and measured from one to twelve inches in height or more. Male and female dolls were often distinguished anatomically and can be told apart by the addition of ivory labrets for males and chin tattooing for females. The information about play dolls within Alaska Native cultures is sporadic. As is so often the case in early museum collections, it is difficult to distinguish dolls made for play from those made for ritual. There were always five dolls making up a family: a father, a mother, a son, a daughter, and a baby. Some human figurines were used by shamans.

The Yupiit Piciryarait Cultural Center (YPCC), also known as Yupiit Piciryarait Cultural Center and Museum, formerly known as the Yup'ik Museum, Library, and Multipurpose Cultural Center, is a non-profit cultural center of the Yup'ik culture centrally located in Bethel, Alaska near the University of Alaska Fairbanks' Kuskokwim Campus and city offices. The center is a unique facility that combines a museum, a library, and multi-purpose cultural activity center including performing arts space, for cultural gatherings, feasts, celebrations, meetings and classes. and that celebrates the Yup'ik culture and serves as a regional cultural center for Southwest Alaska. The name of Yupiit Piciryarait means "Yup'iks' customs" in Yup'ik language and derived from piciryaraq meaning "manner; custom; habit; tradition; way of life" Construction of this cultural facility was completed in 1995, funded through a State appropriation of federal funds. Total cost for construction was $6.15 million. The center was jointly sponsored by the Association of Village Council Presidents (AVCP) and the University of Alaska Fairbanks (UAF) and at the present the center operated by the UAF's Kuskokwim Campus, AVCP and City of Bethel. The building houses three community resources: the Consortium Library, the Yup'ik Museum, and the Multi-purpose room or auditorium. The mission of the center is promote, preserve and develop the traditions of the Yup'ik through traditional and non-traditional art forms of the Alaska Native art, including arts and crafts, performance arts, education, and Yup'ik language. The center also supports local artists and entrepreneurs.

Yup'ik clothing refers to the traditional Eskimo-style clothing worn by the Yupik people of southwestern Alaska. Also known as Cup'ik clothing for the Chevak Cup'ik-speaking people of Chevak and Cup'ig clothing for the Nunivak Cup'ig-speaking people of Nunivak Island.

The consequential mood is a verb form used in some Eskimo–Aleut languages to mark dependent adverbial clauses for reason ('because') or time ('when'). Due to the broader meaning of the term mood in the context of Eskimo grammar, the consequential can be considered outside of the proper scope of grammatical mood.

Yup'ik cuisine refers to the Eskimo style traditional subsistence food and cuisine of the Yup'ik people from the western and southwestern Alaska. Also known as Cup'ik cuisine for the Chevak Cup'ik dialect speaking Eskimos of Chevak and Cup'ig cuisine for the Nunivak Cup'ig dialect speaking Eskimos of Nunivak Island. This cuisine is traditionally based on meat from fish, birds, sea and land mammals, and normally contains high levels of protein. Subsistence foods are generally considered by many to be nutritionally superior superfoods. Yup’ik diet is different from Alaskan Inupiat, Canadian Inuit, and Greenlandic diets. Fish as food are primary food for Yup'ik Eskimos. Both food and fish called neqa in Yup'ik. Food preparation techniques are fermentation and cooking, also uncooked raw. Cooking methods are baking, roasting, barbecuing, frying, smoking, boiling, and steaming. Food preservation methods are mostly drying and less often frozen. Dried fish is usually eaten with seal oil. The ulu or fan-shaped knife used for cutting up fish, meat, food, and such.