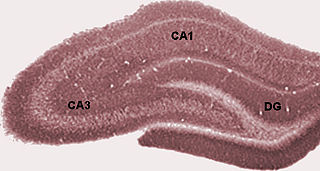

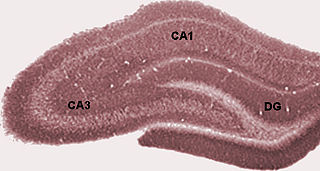

The dentate gyrus (DG) is part of the hippocampal formation in the temporal lobe of the brain, which also includes the hippocampus and the subiculum. The dentate gyrus is part of the hippocampal trisynaptic circuit and is thought to contribute to the formation of new episodic memories, the spontaneous exploration of novel environments and other functions.

Adult neurogenesis is the process in which neurons are generated from neural stem cells in the adult. This process differs from prenatal neurogenesis.

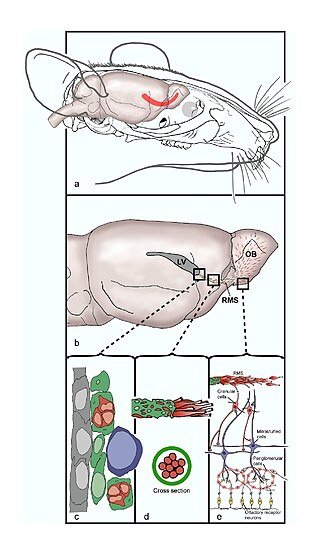

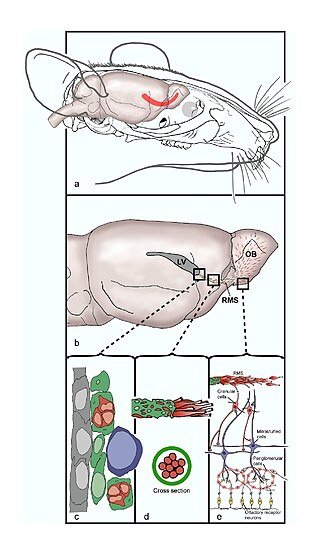

The rostral migratory stream (RMS) is a specialized migratory route found in the brain of some animals along which neuronal precursors that originated in the subventricular zone (SVZ) of the brain migrate to reach the main olfactory bulb (OB). The importance of the RMS lies in its ability to refine and even change an animal's sensitivity to smells, which explains its importance and larger size in the rodent brain as compared to the human brain, as our olfactory sense is not as developed. This pathway has been studied in the rodent, rabbit, and both the squirrel monkey and rhesus monkey. When the neurons reach the OB they differentiate into GABAergic interneurons as they are integrated into either the granule cell layer or periglomerular layer.

Elizabeth Gould is an American neuroscientist and the Dorman T. Warren Professor of Psychology at Princeton University. She was an early investigator of adult neurogenesis in the hippocampus, a research area that continues to be controversial. In November 2002, Discover magazine listed her as one of the 50 most important women scientists.

Neuroepithelial cells, or neuroectodermal cells, form the wall of the closed neural tube in early embryonic development. The neuroepithelial cells span the thickness of the tube's wall, connecting with the pial surface and with the ventricular or lumenal surface. They are joined at the lumen of the tube by junctional complexes, where they form a pseudostratified layer of epithelium called neuroepithelium.

Neural stem cells (NSCs) are self-renewing, multipotent cells that firstly generate the radial glial progenitor cells that generate the neurons and glia of the nervous system of all animals during embryonic development. Some neural progenitor stem cells persist in highly restricted regions in the adult vertebrate brain and continue to produce neurons throughout life. Differences in the size of the central nervous system are among the most important distinctions between the species and thus mutations in the genes that regulate the size of the neural stem cell compartment are among the most important drivers of vertebrate evolution.

Joseph Altman was an American biologist who worked in the field of neurobiology.

Neuropoiesis is the process by which neural stem cells differentiate to form mature neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes in the adult mammal. This process is also referred to as adult neurogenesis.

Brian R. Christie is a Professor of Medicine and Neuroscience at The University of Victoria. He helped found the Neuroscience Graduate Program at the University of Victoria and served as its director from 2010–2017. He is a Michael Smith Senior Scholar Award winner. Christie received his PhD in 1992 from the University of Otago before doing postdoctoral work with Daniel Johnston at Baylor College of Medicine and Terrence Sejnowski at the Salk Institute for Biological Studies, and then became Assistant Professor at the University of British Columbia. Promoted to Associate Professor in 2007. Full Professor in 2013.

The subventricular zone (SVZ) is a region situated on the outside wall of each lateral ventricle of the vertebrate brain. It is present in both the embryonic and adult brain. In embryonic life, the SVZ refers to a secondary proliferative zone containing neural progenitor cells, which divide to produce neurons in the process of neurogenesis. The primary neural stem cells of the brain and spinal cord, termed radial glial cells, instead reside in the ventricular zone (VZ).

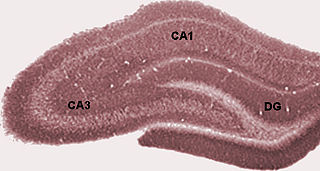

In the hippocampus, the mossy fiber pathway consists of unmyelinated axons projecting from granule cells in the dentate gyrus that terminate on modulatory hilar mossy cells and in Cornu Ammonis area 3 (CA3), a region involved in encoding short-term memory. These axons were first described as mossy fibers by Santiago Ramón y Cajal as they displayed varicosities along their lengths that gave them a mossy appearance. The axons that make up the pathway emerge from the basal portions of the granule cells and pass through the hilus of the dentate gyrus before entering the stratum lucidum of CA3. Granule cell synapses tend to be glutamatergic, though immunohistological data has indicated that some synapses contain neuropeptidergic elements including opiate peptides such as dynorphin and enkephalin. There is also evidence for co-localization of both GABAergic and glutamatergic neurotransmitters within mossy fiber terminals. GABAergic and glutamatergic co-localization in mossy fiber boutons has been observed primarily in the developing hippocampus, but in adulthood, evidence suggests that mossy fiber synapses may alternate which neurotransmitter is released through activity-dependent regulation.

The subgranular zone (SGZ) is a brain region in the hippocampus where adult neurogenesis occurs. The other major site of adult neurogenesis is the subventricular zone (SVZ) in the brain.

Radiation-induced cognitive decline describes the possible correlation between radiation therapy and cognitive impairment. Radiation therapy is used mainly in the treatment of cancer. Radiation therapy can be used to cure care or shrink tumors that are interfering with quality of life. Sometimes radiation therapy is used alone; other times it is used in conjunction with chemotherapy and surgery. For people with brain tumors, radiation can be an effective treatment because chemotherapy is often less effective due to the blood–brain barrier. Unfortunately for some patients, as time passes, people who received radiation therapy may begin experiencing deficits in their learning, memory, and spatial information processing abilities. The learning, memory, and spatial information processing abilities are dependent on proper hippocampus functionality. Therefore, any hippocampus dysfunction will result in deficits in learning, memory, and spatial information processing ability.

Hippocampus anatomy describes the physical aspects and properties of the hippocampus, a neural structure in the medial temporal lobe of the brain. It has a distinctive, curved shape that has been likened to the sea-horse monster of Greek mythology and the ram's horns of Amun in Egyptian mythology. This general layout holds across the full range of mammalian species, from hedgehog to human, although the details vary. For example, in the rat, the two hippocampi look similar to a pair of bananas, joined at the stems. In primate brains, including humans, the portion of the hippocampus near the base of the temporal lobe is much broader than the part at the top. Due to the three-dimensional curvature of this structure, two-dimensional sections such as shown are commonly seen. Neuroimaging pictures can show a number of different shapes, depending on the angle and location of the cut.

The fascia dentata is the earliest stage of the hippocampal circuit. Its primary input is the perforant path from the superficial layers of entorhinal cortex. Its principal neurons are tiny granule cells which give rise to unmyelinated axons called the mossy fibers which project to the hilus and CA3. The fascia dentata of the rat contains approximately 1,000,000 granule cells. It receives feedback connections from mossy cells in the hilus at distant levels in the septal and temporal directions. The fascia dentata and the hilus together make up the dentate gyrus. As with all regions of the hippocampus, the dentate gyrus also receives GABAergic and cholinergic input from the medial septum and the diagonal band of Broca.

The name granule cell has been used for a number of different types of neurons whose only common feature is that they all have very small cell bodies. Granule cells are found within the granular layer of the cerebellum, the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus, the superficial layer of the dorsal cochlear nucleus, the olfactory bulb, and the cerebral cortex.

Endogenous regeneration in the brain is the ability of cells to engage in the repair and regeneration process. While the brain has a limited capacity for regeneration, endogenous neural stem cells, as well as numerous pro-regenerative molecules, can participate in replacing and repairing damaged or diseased neurons and glial cells. Another benefit that can be achieved by using endogenous regeneration could be avoiding an immune response from the host.

Neurogenesis is the process by which nervous system cells, the neurons, are produced by neural stem cells (NSCs). In short, it is brain growth in relation to its organization. This occurs in all species of animals except the porifera (sponges) and placozoans. Types of NSCs include neuroepithelial cells (NECs), radial glial cells (RGCs), basal progenitors (BPs), intermediate neuronal precursors (INPs), subventricular zone astrocytes, and subgranular zone radial astrocytes, among others.

Adult neurogenesis is the process in which new neurons are born and subsequently integrate into functional brain circuits after birth and into adulthood. Avian species including songbirds are among vertebrate species that demonstrate particularly robust adult neurogenesis throughout their telencephalon, in contrast with the more limited neurogenic potential that are observed in adult mammals after birth. Adult neurogenesis in songbirds is observed in brain circuits that underlie complex specialized behavior, including the song control system and the hippocampus. The degree of postnatal and adult neurogenesis in songbirds varies between species, shows sexual dimorphism, fluctuates seasonally, and depends on hormone levels, cell death rates, and social environment. The increased extent of adult neurogenesis in birds compared to other vertebrates, especially in circuits that underlie complex specialized behavior, makes birds an excellent animal model to study this process and its functionality. Methods used in research to track adult neurogenesis in birds include the use of thymidine analogues and identifying endogenous markers of neurogenesis. Historically, the discovery of adult neurogenesis in songbirds substantially contributed to establishing the presence of adult neurogenesis and to progressing a line of research tightly associated with many potential clinical applications.

Adult neurogenesis is the process by which functional, mature neurons are produced from neural stem cells (NSCs) in the adult brain. In most mammals, including humans, it only occurs in the subgranular zone of the hippocampus, and in the olfactory bulb. The neurogenesis hypothesis of depression proposes that major depressive disorder is caused, at least partly, by impaired neurogenesis in the subgranular zone of the hippocampus.