Salah ad-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, commonly known as Saladin, was the founder of the Ayyubid dynasty. Hailing from a Kurdish family, he was the first sultan of both Egypt and Syria. An important figure of the Third Crusade, he spearheaded the Muslim military effort against the Crusader states in the Levant. At the height of his power, the Ayyubid realm spanned Egypt, Syria, Upper Mesopotamia, the Hejaz, Yemen, and Nubia.

The Aqsa Mosque, also known as the Qibli Mosque or Qibli Chapel, is the main congregational mosque or prayer hall in the Al-Aqsa mosque compound in the Old City of Jerusalem. In some sources the building is also named al-Masjid al-Aqṣā, but this name primarily applies to the whole compound in which the building sits, which is itself also known as "Al-Aqsa Mosque". The wider compound is known as Al-Aqsa or Al-Aqsa mosque compound, also known as al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf.

The Ayyubid dynasty, also known as the Ayyubid Sultanate, was the founding dynasty of the medieval Sultanate of Egypt established by Saladin in 1171, following his abolition of the Fatimid Caliphate of Egypt. A Sunni Muslim of Kurdish origin, Saladin had originally served the Zengid ruler Nur ad-Din, leading Nur ad-Din's army in battle against the Crusaders in Fatimid Egypt, where he was made Vizier. Following Nur ad-Din's death, Saladin was proclaimed as the first Sultan of Egypt by the Abbasid Caliphate, and rapidly expanded the new sultanate beyond the frontiers of Egypt to encompass most of the Levant, in addition to Hijaz, Yemen, northern Nubia, Tarabulus, Cyrenaica, southern Anatolia, and northern Iraq, the homeland of his Kurdish family. By virtue of his sultanate including Hijaz, the location of the Islamic holy cities of Mecca and Medina, he was the first ruler to be hailed as the Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques, a title that would be held by all subsequent sultans of Egypt until the Ottoman conquest of 1517. Saladin's military campaigns in the first decade of his rule, aimed at uniting the various Arab and Muslim states in the region against the Crusaders, set the general borders and sphere of influence of the sultanate of Egypt for the almost three and a half centuries of its existence. Most of the Crusader states, including the Kingdom of Jerusalem, fell to Saladin after his victory at the Battle of Hattin in 1187. However, the Crusaders reconquered the coast of Palestine in the 1190s.

The Zengid or Zangid dynasty was an Atabegate of the Seljuk Empire created in 1127. It formed a Turkoman dynasty of Sunni Muslim faith, which ruled parts of the Levant and Upper Mesopotamia, and eventually seized control of Egypt in 1169. In 1174 the Zengid state extended from Tripoli to Hamadan and from Yemen to Sivas. Imad ad-Din Zengi was the first ruler of the dynasty.

Nūr al-Dīn Maḥmūd Zengī, commonly known as Nur ad-Din, was a member of the Zengid dynasty, which ruled the Syrian province of the Seljuk Empire. He reigned from 1146 to 1174. He is regarded as an important figure of the Second Crusade.

A minbar is a pulpit in a mosque where the imam stands to deliver sermons. It is also used in other similar contexts, such as in a Hussainiya where the speaker sits and lectures the congregation.

The Artuqid dynasty was established in 1102 as a Beylik (Principality) of the Seljuk Empire. It formed a Turkoman dynasty rooted in the Oghuz Döğer tribe, and followed the Sunni Muslim faith. It ruled in eastern Anatolia, Northern Syria and Northern Iraq in the eleventh through thirteenth centuries. The Artuqid dynasty took its name from its founder, Artuk Bey, who was of the Döger branch of the Oghuz Turks and ruled one of the Turkmen beyliks of the Seljuk Empire. Artuk's sons and descendants ruled the three branches in the region: Sökmen's descendants ruled the region around Hasankeyf between 1102 and 1231; Ilghazi's branch ruled from Mardin and Mayyafariqin between 1106 and 1186 and Aleppo from 1117–1128; and the Harput line starting in 1112 under the Sökmen branch, and was independent between 1185 and 1233.

The Zahiriyya Library, also known as the Madrasa al-Zahiriyya, is an Islamic library, madrasa, and mausoleum in Damascus, Syria. It was established in 1277, taking its name from the Mamluk sultan Baybars al-Zahir, who is buried in this place.

Abu'l-Faḍl (Abu'l-Hasan) ibn al-Khashshab was the Shi'i qadi and rais of Aleppo during the rule of the Seljuk emir Radwan.

The Citadel of Damascus is a large medieval fortified palace and citadel in Damascus, Syria. It is part of the Ancient City of Damascus, which was listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1979.

Sharaf ad-Dīn al-Muʿaẓẓam ʿĪsā was the Ayyubid Kurdish emir of Damascus from 1218 to 1227. The son of Sultan al-Adil I and nephew of Saladin, founder of the dynasty, al-Mu'azzam was installed by his father as governor of Damascus in 1198 or 1200. After his father's death in 1218, al-Mu'azzam ruled the Ayyubid lands in Syria in his own name, down to his own death in 1227. He was succeeded by his son, an-Nasir Dawud.

ʿIṣmat ad-Dīn Khātūn, also known as Asimat, was the daughter of Mu'in ad-Din Unur, regent of Damascus. She had been the wife of two of the greatest Muslim generals of the 12th century, Nur ad-Din and Saladin.

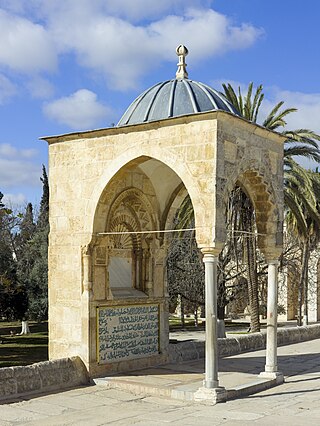

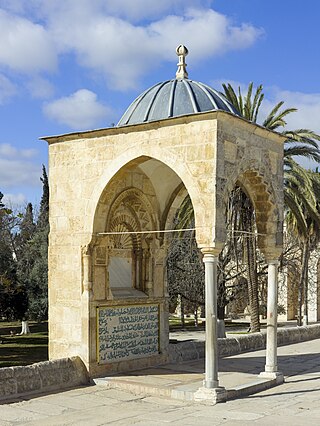

The Dome of the Ascension is a small Islamic free-standing domed structure built by the Umayyads that stands just north the Dome of the Rock on the al-Aqsa compound in Jerusalem.

The Dome of Yusuf is a free-standing domed structure on the Temple Mount, located south of the Dome of the Rock.

The Great Mosque of Aleppo is the largest and one of the oldest mosques in the city of Aleppo, Syria. It is located in al-Jalloum district of the Ancient City of Aleppo, a World Heritage Site, near the entrance to Al-Madina Souq. The mosque is purportedly home to the remains of Zechariah, the father of John the Baptist, both of whom are revered in Islam and Christianity. It was built in the beginning of the 8th century CE. However, the current building dates back to the 11th through 14th centuries. The minaret in the mosque was built in 1090, and was destroyed during fighting in the Syrian Civil War in April 2013.

The Islamic Museum is a museum at Al Aqsa in the Old City section of Jerusalem. On display are exhibits from ten periods of Islamic history encompassing several Muslim regions. The museum is west of al-Aqsa Mosque, across a courtyard.

Gökböri, or Muzaffar ad-Din Gökböri, was a leading emir and general of Sultan Saladin, and ruler of Erbil. He served both the Zengid and Ayyubid rulers of Syria and Egypt. He played a pivotal role in Saladin's conquest of Northern Syria and the Jazira and later held major commands in a number of battles against the Crusader states and the forces of the Third Crusade. He was known as Manafaradin, a corruption of his principal praise name, to the Franks of the Crusader states.

The minbar of the Ibrahimi Mosque is an 11th-century minbar in the Ibrahimi Mosque in Hebron, West Bank. The minbar was commissioned by the Fatimid vizier Badr al-Jamali in 1091 for the Shrine of Husayn's Head in Ascalon but was moved to its current location by Salah ad-Din (Saladin) in 1191.

Al-Aqsa or al-Masjid al-Aqṣā is the compound of Islamic religious buildings that sit atop the Temple Mount, also known as the Haram al-Sharif, in the Old City of Jerusalem, including the Dome of the Rock, many mosques and prayer halls, madrasas, zawiyas, khalwas and other domes and religious structures, as well as the four encircling minarets. It is considered the third holiest site in Islam. The compound's main congregational mosque or prayer hall is variously known as Al-Aqsa Mosque, Qibli Mosque or al-Jāmiʿ al-Aqṣā, while in some sources it is also known as al-Masjid al-Aqṣā; the wider compound is sometimes known as Al-Aqsa mosque compound in order to avoid confusion.

The Shrine of Husayn's Head was a shrine built by the Fatimids on a hilltop adjacent to Ascalon that was reputed to have held the head of Husayn ibn Ali between c. 906 CE and 1153 CE. It was described as the most magnificent building in the ancient city, and developed into the most important and holiest Shi'a site in Palestine.