Linear MMSE estimator

In many cases, it is not possible to determine the analytical expression of the MMSE estimator. Two basic numerical approaches to obtain the MMSE estimate depends on either finding the conditional expectation  or finding the minima of MSE. Direct numerical evaluation of the conditional expectation is computationally expensive since it often requires multidimensional integration usually done via Monte Carlo methods. Another computational approach is to directly seek the minima of the MSE using techniques such as the stochastic gradient descent methods; but this method still requires the evaluation of expectation. While these numerical methods have been fruitful, a closed form expression for the MMSE estimator is nevertheless possible if we are willing to make some compromises.

or finding the minima of MSE. Direct numerical evaluation of the conditional expectation is computationally expensive since it often requires multidimensional integration usually done via Monte Carlo methods. Another computational approach is to directly seek the minima of the MSE using techniques such as the stochastic gradient descent methods; but this method still requires the evaluation of expectation. While these numerical methods have been fruitful, a closed form expression for the MMSE estimator is nevertheless possible if we are willing to make some compromises.

One possibility is to abandon the full optimality requirements and seek a technique minimizing the MSE within a particular class of estimators, such as the class of linear estimators. Thus, we postulate that the conditional expectation of  given

given  is a simple linear function of

is a simple linear function of  ,

,  , where the measurement

, where the measurement  is a random vector,

is a random vector,  is a matrix and

is a matrix and  is a vector. This can be seen as the first order Taylor approximation of

is a vector. This can be seen as the first order Taylor approximation of  . The linear MMSE estimator is the estimator achieving minimum MSE among all estimators of such form. That is, it solves the following optimization problem:

. The linear MMSE estimator is the estimator achieving minimum MSE among all estimators of such form. That is, it solves the following optimization problem:

One advantage of such linear MMSE estimator is that it is not necessary to explicitly calculate the posterior probability density function of  . Such linear estimator only depends on the first two moments of

. Such linear estimator only depends on the first two moments of  and

and  . So although it may be convenient to assume that

. So although it may be convenient to assume that  and

and  are jointly Gaussian, it is not necessary to make this assumption, so long as the assumed distribution has well defined first and second moments. The form of the linear estimator does not depend on the type of the assumed underlying distribution.

are jointly Gaussian, it is not necessary to make this assumption, so long as the assumed distribution has well defined first and second moments. The form of the linear estimator does not depend on the type of the assumed underlying distribution.

The expression for optimal  and

and  is given by:

is given by:

where  ,

,  the

the  is cross-covariance matrix between

is cross-covariance matrix between  and

and  , the

, the  is auto-covariance matrix of

is auto-covariance matrix of  .

.

Thus, the expression for linear MMSE estimator, its mean, and its auto-covariance is given by

where the  is cross-covariance matrix between

is cross-covariance matrix between  and

and  .

.

Lastly, the error covariance and minimum mean square error achievable by such estimator is

Derivation using orthogonality principle

Let us have the optimal linear MMSE estimator given as  , where we are required to find the expression for

, where we are required to find the expression for  and

and  . It is required that the MMSE estimator be unbiased. This means,

. It is required that the MMSE estimator be unbiased. This means,

Plugging the expression for  in above, we get

in above, we get

where  and

and  . Thus we can re-write the estimator as

. Thus we can re-write the estimator as

and the expression for estimation error becomes

From the orthogonality principle, we can have  , where we take

, where we take  . Here the left-hand-side term is

. Here the left-hand-side term is

When equated to zero, we obtain the desired expression for  as

as

The  is cross-covariance matrix between X and Y, and

is cross-covariance matrix between X and Y, and  is auto-covariance matrix of Y. Since

is auto-covariance matrix of Y. Since  , the expression can also be re-written in terms of

, the expression can also be re-written in terms of  as

as

Thus the full expression for the linear MMSE estimator is

Since the estimate  is itself a random variable with

is itself a random variable with  , we can also obtain its auto-covariance as

, we can also obtain its auto-covariance as

Putting the expression for  and

and  , we get

, we get

Lastly, the covariance of linear MMSE estimation error will then be given by

The first term in the third line is zero due to the orthogonality principle. Since  , we can re-write

, we can re-write  in terms of covariance matrices as

in terms of covariance matrices as

This we can recognize to be the same as  Thus the minimum mean square error achievable by such a linear estimator is

Thus the minimum mean square error achievable by such a linear estimator is

.

.

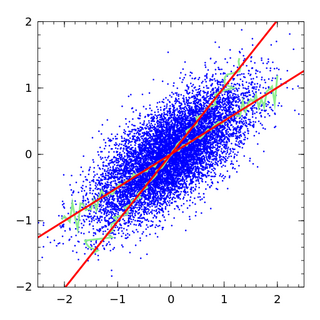

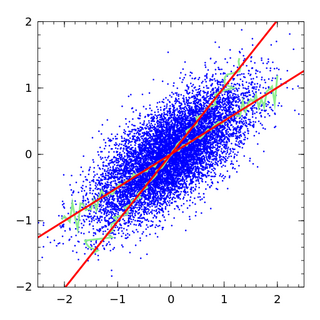

Univariate case

For the special case when both  and

and  are scalars, the above relations simplify to

are scalars, the above relations simplify to

where  is the Pearson's correlation coefficient between

is the Pearson's correlation coefficient between  and

and  .

.

The above two equations allows us to interpret the correlation coefficient either as normalized slope of linear regression

or as square root of the ratio of two variances

.

.

When  , we have

, we have  and

and  . In this case, no new information is gleaned from the measurement which can decrease the uncertainty in

. In this case, no new information is gleaned from the measurement which can decrease the uncertainty in  . On the other hand, when

. On the other hand, when  , we have

, we have  and

and  . Here

. Here  is completely determined by

is completely determined by  , as given by the equation of straight line.

, as given by the equation of straight line.

Linear MMSE estimator for linear observation process

Let us further model the underlying process of observation as a linear process:  , where

, where  is a known matrix and

is a known matrix and  is random noise vector with the mean

is random noise vector with the mean  and cross-covariance

and cross-covariance  . Here the required mean and the covariance matrices will be

. Here the required mean and the covariance matrices will be

Thus the expression for the linear MMSE estimator matrix  further modifies to

further modifies to

Putting everything into the expression for  , we get

, we get

Lastly, the error covariance is

The significant difference between the estimation problem treated above and those of least squares and Gauss–Markov estimate is that the number of observations m, (i.e. the dimension of  ) need not be at least as large as the number of unknowns, n, (i.e. the dimension of

) need not be at least as large as the number of unknowns, n, (i.e. the dimension of  ). The estimate for the linear observation process exists so long as the m-by-m matrix

). The estimate for the linear observation process exists so long as the m-by-m matrix  exists; this is the case for any m if, for instance,

exists; this is the case for any m if, for instance,  is positive definite. Physically the reason for this property is that since

is positive definite. Physically the reason for this property is that since  is now a random variable, it is possible to form a meaningful estimate (namely its mean) even with no measurements. Every new measurement simply provides additional information which may modify our original estimate. Another feature of this estimate is that for m < n, there need be no measurement error. Thus, we may have

is now a random variable, it is possible to form a meaningful estimate (namely its mean) even with no measurements. Every new measurement simply provides additional information which may modify our original estimate. Another feature of this estimate is that for m < n, there need be no measurement error. Thus, we may have  , because as long as

, because as long as  is positive definite, the estimate still exists. Lastly, this technique can handle cases where the noise is correlated.

is positive definite, the estimate still exists. Lastly, this technique can handle cases where the noise is correlated.

An alternative form of expression can be obtained by using the matrix identity

which can be established by post-multiplying by  and pre-multiplying by

and pre-multiplying by  to obtain

to obtain

and

Since  can now be written in terms of

can now be written in terms of  as

as  , we get a simplified expression for

, we get a simplified expression for  as

as

In this form the above expression can be easily compared with ridge regression, weighed least square and Gauss–Markov estimate. In particular, when  , corresponding to infinite variance of the apriori information concerning

, corresponding to infinite variance of the apriori information concerning  , the result

, the result  is identical to the weighed linear least square estimate with

is identical to the weighed linear least square estimate with  as the weight matrix. Moreover, if the components of

as the weight matrix. Moreover, if the components of  are uncorrelated and have equal variance such that

are uncorrelated and have equal variance such that  where

where  is an identity matrix, then

is an identity matrix, then  is identical to the ordinary least square estimate. When apriori information is available as

is identical to the ordinary least square estimate. When apriori information is available as  and the

and the  are uncorrelated and have equal variance, we have

are uncorrelated and have equal variance, we have  , which is identical to ridge regression solution.

, which is identical to ridge regression solution.

Sequential linear MMSE estimation

In many real-time applications, observational data is not available in a single batch. Instead the observations are made in a sequence. One possible approach is to use the sequential observations to update an old estimate as additional data becomes available, leading to finer estimates. One crucial difference between batch estimation and sequential estimation is that sequential estimation requires an additional Markov assumption.

In the Bayesian framework, such recursive estimation is easily facilitated using Bayes' rule. Given  observations,

observations,  , Bayes' rule gives us the posterior density of

, Bayes' rule gives us the posterior density of  as

as

The  is called the posterior density,

is called the posterior density,  is called the likelihood function, and

is called the likelihood function, and  is the prior density of k-th time step. Here we have assumed the conditional independence of

is the prior density of k-th time step. Here we have assumed the conditional independence of  from previous observations

from previous observations  given

given  as

as

This is the Markov assumption.

The MMSE estimate  given the k-th observation is then the mean of the posterior density

given the k-th observation is then the mean of the posterior density  . With the lack of dynamical information on how the state

. With the lack of dynamical information on how the state  changes with time, we will make a further stationarity assumption about the prior:

changes with time, we will make a further stationarity assumption about the prior:

Thus, the prior density for k-th time step is the posterior density of (k-1)-th time step. This structure allows us to formulate a recursive approach to estimation.

In the context of linear MMSE estimator, the formula for the estimate will have the same form as before:  However, the mean and covariance matrices of

However, the mean and covariance matrices of  and

and  will need to be replaced by those of the prior density

will need to be replaced by those of the prior density  and likelihood

and likelihood  , respectively.

, respectively.

For the prior density  , its mean is given by the previous MMSE estimate,

, its mean is given by the previous MMSE estimate,

,

,

and its covariance matrix is given by the previous error covariance matrix,

as per by the properties of MMSE estimators and the stationarity assumption.

Similarly, for the linear observation process, the mean of the likelihood  is given by

is given by  and the covariance matrix is as before

and the covariance matrix is as before

.

.

The difference between the predicted value of  , as given by

, as given by  , and its observed value

, and its observed value  gives the prediction error

gives the prediction error  , which is also referred to as innovation or residual. It is more convenient to represent the linear MMSE in terms of the prediction error, whose mean and covariance are

, which is also referred to as innovation or residual. It is more convenient to represent the linear MMSE in terms of the prediction error, whose mean and covariance are  and

and  .

.

Hence, in the estimate update formula, we should replace  and

and  by

by  and

and  , respectively. Also, we should replace

, respectively. Also, we should replace  and

and  by

by  and

and  . Lastly, we replace

. Lastly, we replace  by

by

Thus, we have the new estimate as new observation  arrives as

arrives as

and the new error covariance as

From the point of view of linear algebra, for sequential estimation, if we have an estimate  based on measurements generating space

based on measurements generating space  , then after receiving another set of measurements, we should subtract out from these measurements that part that could be anticipated from the result of the first measurements. In other words, the updating must be based on that part of the new data which is orthogonal to the old data.

, then after receiving another set of measurements, we should subtract out from these measurements that part that could be anticipated from the result of the first measurements. In other words, the updating must be based on that part of the new data which is orthogonal to the old data.

The repeated use of the above two equations as more observations become available lead to recursive estimation techniques. The expressions can be more compactly written as

The matrix  is often referred to as the Kalman gain factor. The alternative formulation of the above algorithm will give

is often referred to as the Kalman gain factor. The alternative formulation of the above algorithm will give

The repetition of these three steps as more data becomes available leads to an iterative estimation algorithm. The generalization of this idea to non-stationary cases gives rise to the Kalman filter. The three update steps outlined above indeed form the update step of the Kalman filter.

Special case: scalar observations

As an important special case, an easy to use recursive expression can be derived when at each k-th time instant the underlying linear observation process yields a scalar such that  , where

, where  is n-by-1 known column vector whose values can change with time,

is n-by-1 known column vector whose values can change with time,  is n-by-1 random column vector to be estimated, and

is n-by-1 random column vector to be estimated, and  is scalar noise term with variance

is scalar noise term with variance  . After (k+1)-th observation, the direct use of above recursive equations give the expression for the estimate

. After (k+1)-th observation, the direct use of above recursive equations give the expression for the estimate  as:

as:

where  is the new scalar observation and the gain factor

is the new scalar observation and the gain factor  is n-by-1 column vector given by

is n-by-1 column vector given by

The  is n-by-n error covariance matrix given by

is n-by-n error covariance matrix given by

Here, no matrix inversion is required. Also, the gain factor,  , depends on our confidence in the new data sample, as measured by the noise variance, versus that in the previous data. The initial values of

, depends on our confidence in the new data sample, as measured by the noise variance, versus that in the previous data. The initial values of  and

and  are taken to be the mean and covariance of the aprior probability density function of

are taken to be the mean and covariance of the aprior probability density function of  .

.

Alternative approaches: This important special case has also given rise to many other iterative methods (or adaptive filters), such as the least mean squares filter and recursive least squares filter, that directly solves the original MSE optimization problem using stochastic gradient descents. However, since the estimation error  cannot be directly observed, these methods try to minimize the mean squared prediction error

cannot be directly observed, these methods try to minimize the mean squared prediction error  . For instance, in the case of scalar observations, we have the gradient

. For instance, in the case of scalar observations, we have the gradient  Thus, the update equation for the least mean square filter is given by

Thus, the update equation for the least mean square filter is given by

where  is the scalar step size and the expectation is approximated by the instantaneous value

is the scalar step size and the expectation is approximated by the instantaneous value  . As we can see, these methods bypass the need for covariance matrices.

. As we can see, these methods bypass the need for covariance matrices.

In many practical applications, the observation noise is uncorrelated. That is,  is a diagonal matrix. In such cases, it is advantageous to consider the components of

is a diagonal matrix. In such cases, it is advantageous to consider the components of  as independent scalar measurements, rather than vector measurement. This allows us to reduce computation time by processing the

as independent scalar measurements, rather than vector measurement. This allows us to reduce computation time by processing the  measurement vector as

measurement vector as  scalar measurements. The use of scalar update formula avoids matrix inversion in the implementation of the covariance update equations, thus improving the numerical robustness against roundoff errors. The update can be implemented iteratively as:

scalar measurements. The use of scalar update formula avoids matrix inversion in the implementation of the covariance update equations, thus improving the numerical robustness against roundoff errors. The update can be implemented iteratively as:

where  , using the initial values

, using the initial values  and

and  . The intermediate variables

. The intermediate variables  is the

is the  -th diagonal element of the

-th diagonal element of the  diagonal matrix

diagonal matrix  ; while

; while  is the

is the  -th row of

-th row of  matrix

matrix  . The final values are

. The final values are  and

and  .

.

Examples

Example 1

We shall take a linear prediction problem as an example. Let a linear combination of observed scalar random variables  and

and  be used to estimate another future scalar random variable

be used to estimate another future scalar random variable  such that

such that  . If the random variables

. If the random variables  are real Gaussian random variables with zero mean and its covariance matrix given by

are real Gaussian random variables with zero mean and its covariance matrix given by

then our task is to find the coefficients  such that it will yield an optimal linear estimate

such that it will yield an optimal linear estimate  .

.

In terms of the terminology developed in the previous sections, for this problem we have the observation vector  , the estimator matrix

, the estimator matrix  as a row vector, and the estimated variable

as a row vector, and the estimated variable  as a scalar quantity. The autocorrelation matrix

as a scalar quantity. The autocorrelation matrix  is defined as

is defined as

The cross correlation matrix  is defined as

is defined as

We now solve the equation  by inverting

by inverting  and pre-multiplying to get

and pre-multiplying to get

So we have

and

and  as the optimal coefficients for

as the optimal coefficients for  . Computing the minimum mean square error then gives

. Computing the minimum mean square error then gives  . [2] Note that it is not necessary to obtain an explicit matrix inverse of

. [2] Note that it is not necessary to obtain an explicit matrix inverse of  to compute the value of

to compute the value of  . The matrix equation can be solved by well known methods such as Gauss elimination method. A shorter, non-numerical example can be found in orthogonality principle.

. The matrix equation can be solved by well known methods such as Gauss elimination method. A shorter, non-numerical example can be found in orthogonality principle.

Example 2

Consider a vector  formed by taking

formed by taking  observations of a fixed but unknown scalar parameter

observations of a fixed but unknown scalar parameter  disturbed by white Gaussian noise. We can describe the process by a linear equation

disturbed by white Gaussian noise. We can describe the process by a linear equation  , where

, where  . Depending on context it will be clear if

. Depending on context it will be clear if  represents a scalar or a vector. Suppose that we know

represents a scalar or a vector. Suppose that we know  to be the range within which the value of

to be the range within which the value of  is going to fall in. We can model our uncertainty of

is going to fall in. We can model our uncertainty of  by an aprior uniform distribution over an interval

by an aprior uniform distribution over an interval  , and thus

, and thus  will have variance of

will have variance of  . Let the noise vector

. Let the noise vector  be normally distributed as

be normally distributed as  where

where  is an identity matrix. Also

is an identity matrix. Also  and

and  are independent and

are independent and  . It is easy to see that

. It is easy to see that

Thus, the linear MMSE estimator is given by

We can simplify the expression by using the alternative form for  as

as

where for  we have

we have

Similarly, the variance of the estimator is

Thus the MMSE of this linear estimator is

For very large  , we see that the MMSE estimator of a scalar with uniform aprior distribution can be approximated by the arithmetic average of all the observed data

, we see that the MMSE estimator of a scalar with uniform aprior distribution can be approximated by the arithmetic average of all the observed data

while the variance will be unaffected by data  and the LMMSE of the estimate will tend to zero.

and the LMMSE of the estimate will tend to zero.

However, the estimator is suboptimal since it is constrained to be linear. Had the random variable  also been Gaussian, then the estimator would have been optimal. Notice, that the form of the estimator will remain unchanged, regardless of the apriori distribution of

also been Gaussian, then the estimator would have been optimal. Notice, that the form of the estimator will remain unchanged, regardless of the apriori distribution of  , so long as the mean and variance of these distributions are the same.

, so long as the mean and variance of these distributions are the same.

Example 3

Consider a variation of the above example: Two candidates are standing for an election. Let the fraction of votes that a candidate will receive on an election day be  Thus the fraction of votes the other candidate will receive will be

Thus the fraction of votes the other candidate will receive will be  We shall take

We shall take  as a random variable with a uniform prior distribution over

as a random variable with a uniform prior distribution over  so that its mean is

so that its mean is  and variance is

and variance is  A few weeks before the election, two independent public opinion polls were conducted by two different pollsters. The first poll revealed that the candidate is likely to get

A few weeks before the election, two independent public opinion polls were conducted by two different pollsters. The first poll revealed that the candidate is likely to get  fraction of votes. Since some error is always present due to finite sampling and the particular polling methodology adopted, the first pollster declares their estimate to have an error

fraction of votes. Since some error is always present due to finite sampling and the particular polling methodology adopted, the first pollster declares their estimate to have an error  with zero mean and variance

with zero mean and variance  Similarly, the second pollster declares their estimate to be

Similarly, the second pollster declares their estimate to be  with an error

with an error  with zero mean and variance

with zero mean and variance  Note that except for the mean and variance of the error, the error distribution is unspecified. How should the two polls be combined to obtain the voting prediction for the given candidate?

Note that except for the mean and variance of the error, the error distribution is unspecified. How should the two polls be combined to obtain the voting prediction for the given candidate?

As with previous example, we have

Here, both the  . Thus, we can obtain the LMMSE estimate as the linear combination of

. Thus, we can obtain the LMMSE estimate as the linear combination of  and

and  as

as

where the weights are given by

Here, since the denominator term is constant, the poll with lower error is given higher weight in order to predict the election outcome. Lastly, the variance of  is given by

is given by

which makes  smaller than

smaller than  Thus, the LMMSE is given by

Thus, the LMMSE is given by

In general, if we have  pollsters, then

pollsters, then  where the weight for i-th pollster is given by

where the weight for i-th pollster is given by  and the LMMSE is given by

and the LMMSE is given by

In probability theory and statistics, variance is the expected value of the squared deviation from the mean of a random variable. The standard deviation (SD) is obtained as the square root of the variance. Variance is a measure of dispersion, meaning it is a measure of how far a set of numbers is spread out from their average value. It is the second central moment of a distribution, and the covariance of the random variable with itself, and it is often represented by , , , , or .

The weighted arithmetic mean is similar to an ordinary arithmetic mean, except that instead of each of the data points contributing equally to the final average, some data points contribute more than others. The notion of weighted mean plays a role in descriptive statistics and also occurs in a more general form in several other areas of mathematics.

In probability theory and statistics, the multivariate normal distribution, multivariate Gaussian distribution, or joint normal distribution is a generalization of the one-dimensional (univariate) normal distribution to higher dimensions. One definition is that a random vector is said to be k-variate normally distributed if every linear combination of its k components has a univariate normal distribution. Its importance derives mainly from the multivariate central limit theorem. The multivariate normal distribution is often used to describe, at least approximately, any set of (possibly) correlated real-valued random variables each of which clusters around a mean value.

In statistics, maximum likelihood estimation (MLE) is a method of estimating the parameters of an assumed probability distribution, given some observed data. This is achieved by maximizing a likelihood function so that, under the assumed statistical model, the observed data is most probable. The point in the parameter space that maximizes the likelihood function is called the maximum likelihood estimate. The logic of maximum likelihood is both intuitive and flexible, and as such the method has become a dominant means of statistical inference.

In statistics, correlation or dependence is any statistical relationship, whether causal or not, between two random variables or bivariate data. Although in the broadest sense, "correlation" may indicate any type of association, in statistics it usually refers to the degree to which a pair of variables are linearly related. Familiar examples of dependent phenomena include the correlation between the height of parents and their offspring, and the correlation between the price of a good and the quantity the consumers are willing to purchase, as it is depicted in the so-called demand curve.

Covariance in probability theory and statistics is a measure of the joint variability of two random variables.

In probability theory and statistics, a covariance matrix is a square matrix giving the covariance between each pair of elements of a given random vector.

In statistics, the mean squared error (MSE) or mean squared deviation (MSD) of an estimator measures the average of the squares of the errors—that is, the average squared difference between the estimated values and the actual value. MSE is a risk function, corresponding to the expected value of the squared error loss. The fact that MSE is almost always strictly positive is because of randomness or because the estimator does not account for information that could produce a more accurate estimate. In machine learning, specifically empirical risk minimization, MSE may refer to the empirical risk, as an estimate of the true MSE.

In statistics, the Pearson correlation coefficient (PCC) is a correlation coefficient that measures linear correlation between two sets of data. It is the ratio between the covariance of two variables and the product of their standard deviations; thus, it is essentially a normalized measurement of the covariance, such that the result always has a value between −1 and 1. As with covariance itself, the measure can only reflect a linear correlation of variables, and ignores many other types of relationships or correlations. As a simple example, one would expect the age and height of a sample of teenagers from a high school to have a Pearson correlation coefficient significantly greater than 0, but less than 1.

In statistics, sometimes the covariance matrix of a multivariate random variable is not known but has to be estimated. Estimation of covariance matrices then deals with the question of how to approximate the actual covariance matrix on the basis of a sample from the multivariate distribution. Simple cases, where observations are complete, can be dealt with by using the sample covariance matrix. The sample covariance matrix (SCM) is an unbiased and efficient estimator of the covariance matrix if the space of covariance matrices is viewed as an extrinsic convex cone in Rp×p; however, measured using the intrinsic geometry of positive-definite matrices, the SCM is a biased and inefficient estimator. In addition, if the random variable has a normal distribution, the sample covariance matrix has a Wishart distribution and a slightly differently scaled version of it is the maximum likelihood estimate. Cases involving missing data, heteroscedasticity, or autocorrelated residuals require deeper considerations. Another issue is the robustness to outliers, to which sample covariance matrices are highly sensitive.

In statistics, ordinary least squares (OLS) is a type of linear least squares method for choosing the unknown parameters in a linear regression model by the principle of least squares: minimizing the sum of the squares of the differences between the observed dependent variable in the input dataset and the output of the (linear) function of the independent variable.

Weighted least squares (WLS), also known as weighted linear regression, is a generalization of ordinary least squares and linear regression in which knowledge of the unequal variance of observations (heteroscedasticity) is incorporated into the regression. WLS is also a specialization of generalized least squares, when all the off-diagonal entries of the covariance matrix of the errors, are null.

In statistics, generalized least squares (GLS) is a method used to estimate the unknown parameters in a linear regression model. It is used when there is a non-zero amount of correlation between the residuals in the regression model. GLS is employed to improve statistical efficiency and reduce the risk of drawing erroneous inferences, as compared to conventional least squares and weighted least squares methods. It was first described by Alexander Aitken in 1935.

In statistics, the bias of an estimator is the difference between this estimator's expected value and the true value of the parameter being estimated. An estimator or decision rule with zero bias is called unbiased. In statistics, "bias" is an objective property of an estimator. Bias is a distinct concept from consistency: consistent estimators converge in probability to the true value of the parameter, but may be biased or unbiased; see bias versus consistency for more.

In probability theory and statistics, partial correlation measures the degree of association between two random variables, with the effect of a set of controlling random variables removed. When determining the numerical relationship between two variables of interest, using their correlation coefficient will give misleading results if there is another confounding variable that is numerically related to both variables of interest. This misleading information can be avoided by controlling for the confounding variable, which is done by computing the partial correlation coefficient. This is precisely the motivation for including other right-side variables in a multiple regression; but while multiple regression gives unbiased results for the effect size, it does not give a numerical value of a measure of the strength of the relationship between the two variables of interest.

The topic of heteroskedasticity-consistent (HC) standard errors arises in statistics and econometrics in the context of linear regression and time series analysis. These are also known as heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors, Eicker–Huber–White standard errors, to recognize the contributions of Friedhelm Eicker, Peter J. Huber, and Halbert White.

In statistics, principal component regression (PCR) is a regression analysis technique that is based on principal component analysis (PCA). More specifically, PCR is used for estimating the unknown regression coefficients in a standard linear regression model.

In statistics and signal processing, the orthogonality principle is a necessary and sufficient condition for the optimality of a Bayesian estimator. Loosely stated, the orthogonality principle says that the error vector of the optimal estimator is orthogonal to any possible estimator. The orthogonality principle is most commonly stated for linear estimators, but more general formulations are possible. Since the principle is a necessary and sufficient condition for optimality, it can be used to find the minimum mean square error estimator.

In statistics, errors-in-variables models or measurement error models are regression models that account for measurement errors in the independent variables. In contrast, standard regression models assume that those regressors have been measured exactly, or observed without error; as such, those models account only for errors in the dependent variables, or responses.

SAMV is a parameter-free superresolution algorithm for the linear inverse problem in spectral estimation, direction-of-arrival (DOA) estimation and tomographic reconstruction with applications in signal processing, medical imaging and remote sensing. The name was coined in 2013 to emphasize its basis on the asymptotically minimum variance (AMV) criterion. It is a powerful tool for the recovery of both the amplitude and frequency characteristics of multiple highly correlated sources in challenging environments. Applications include synthetic-aperture radar, computed tomography scan, and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).